What do you think would be the aftermath of the concentration camps? Bitterness, depression, anger? There were those, of course, as momentary feelings, and I’ve forgiven the camps if only to escape being trapped in the psychological emasculation programming. But the predominant feelings were confusion and bewilderment. Why did the all-mighty government incarcerate us Japanese and Japanese Americans (75 percent of us were born in America) in concentration camps euphemistically called “relocation centers”? It was because President Franklin D. Roosevelt decreed it so with the signing of Executive Order 9066 that set into motion the mass evacuation and the construction of ten camps in the most hostile climes of the United States.

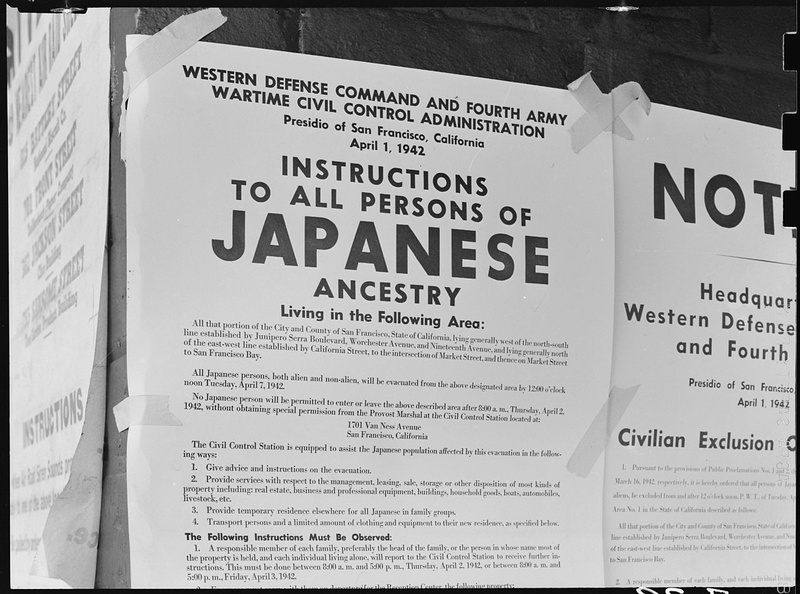

I was mostly confused as a boy of nine by the announcement tacked up on the telephone poles. I was just a kid. I never harmed anybody. I wasn’t a spy or anything like that. My father, who rented a fishing boat as he plied the waters off San Pedro, California was arrested by the FBI and sent to detention centers in the hinterlands of America, because he was suspected of contacting enemy Japanese submarines. (I didn’t see him for over two years.)

I told the landlord of the small flat we rented in Redondo Beach to take good care of my pup, Eddie, because I would be back in two weeks—after the adults who ran the affairs of the world got together to iron out what had to be a gross misunderstanding. When I realized it was because of the way I looked, it was a rude awakening and introduction to the world of racism. You look like the enemy, therefore you are the enemy. It was a simple equation—too simple. It was a rotten comic book world.

My mother and I, identified by tagged numbers, got on the train with an armed MP at either end of the coach and endured the heat with the shades drawn to Tulare, California where we were bussed to the camp, our first introduction to high barbed wire fences and gun towers.

The time was May 1942. We stayed there for five months before moving to a more permanent camp in Gila River Indian Reservation in Arizona. It was in the middle of a desert populated by poisonous denizens such as rattle snakes, Gila monsters, coral snakes, scorpions, poisonous toads.

Uncomfortable being alone and confused, my mother petitioned the authorities to move us to a camp where we had relatives and so we wound up at Heart Mountain, Wyoming where my mother took ill and couldn’t be treated at the camp infirmary and had to be sent to California. I went down to Texas to join my father at Crystal City, a family camp run by the Department of Justice rather than the War Relocation Authority which managed the ten “relocation centers”.

From Crystal City, my father, an Issei (first generation immigrant), my mother, a Nisei who joined us at San Pedro, and I got on the repatriation vessel and began the ten-day journey to war-torn Japan. We arrived at Uraga, a former Japanese naval base south of Yokohama, in March of 1946 and were transferred to the Japanese authorities and introduced to the hardships of a defeated, prostrated country.

I grew up in isolated exile, a young American teenage lookalike outsider who spent thirteen years in postwar Japan, growing up there into adulthood before I was able to return to the United States in 1959. In the meantime, I went to St. Joseph College, a Marianist high school in Yokohama, graduated in 1953 and was recruited by a U.S. intelligence agency to be an interpreter/translator.

Managing to return to my beloved America, I got married and settled down to complete my college education at the University of Washington where I earned a B.A. in English, Advanced Writing, and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. I was also editor in chief of the campus literary magazine, Assay. I was always interested in writing and wanted to become a novelist—a distant, impossible dream, it seemed earlier in my life. But I have persevered and published to date six works of fiction. In all my works, I address the issue of the concentration camps, a pivotal chapter in my life. I also taught briefly at the university level before embarking on my writing career.

What does all this amount to? What did all the sound and fury of the war, Executive Order 9066, the concentration camps result in? How about the civil rights movement and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr? And the Black Lives Matter movement? We are still as racist as ever. Witness the proliferating incidents of racial violence against Asian Americans—today.

Is this a repeat performance of the erstwhile persecution mentality against those perceived to represent the Yellow Peril of the late 1800s? We strive to better ourselves only to confront an endemic wall of non-acceptance. The racial divisions have only grown in the recent past. Is it all a crock? A sublime crock because America is supposed to be a Christian nation. Where is the all-essential love? We are drowning in the concomitants of hate. Do we embrace God for guidance? Follow the teachings of Jesus or the essence thereof? Though potentially a partial answer, that hasn’t done any good so far.

But what does all this amount to? First, what is racism? Is it an expression of our lesser angels? An absence of decency? An unholy itch? I say call it what it is…call a spade a spade. Racism is a mental disorder, a blight on the national psyche. It is a pernicious, insidious disease that is highly contagious and can be communicated to susceptible minds—and hearts.

Racism can be communicated and spread by word and deed, by thought and utterance. And racism can spread like wildfire just as any contagious virus. We are in a pandemic of racism amid an actual pandemic of a virus called COVID-19. Racism is like a fever that sweeps through the mind, raising unseemly thoughts of one’s neighbor founded on one’s falsely assumed superiority. It is like a disease that ravages the mind, heart and soul and goes to the quick of a person’s makeup, there to assume gargantuan proportions of an unearned sense of personal importance.

What can we do about racism? Clearly, it is not wanted. It’s not even necessary—in human interactions. It is a noxious irritant, oftentimes deadly. What we can do is hold it at arm’s length and treat it objectively—as a mental disorder. Discuss it as such, analyze and treat it as a disease in therapy groups and enter it in the psychiatric handbook as a form of mental illness to be cured.

Who wants to be identified as a racist with all its abhorrent traits? Only the pathologically unhinged. An ordinary person would want to avoid being stigmatized as a racist like the plague once it is seen as a gross aberration from the norm. We must legislate it out of existence. The hate laws are just a mere beginning, a step in the right direction. Racism is an expensive, miserable habit. It is an immoral addiction, a destructive bent that finds its roots in those with unresolved issues dealing with one’s supposed supremacy. When are we going to learn that racism and hate are but a mirror reflection of how one regards oneself? Accept yourself as a person, warts and all, and you will accept another as a human being.

Racism is an avenue which can be used to divide America. Lest we give our enemies the opportunity to divide and conquer, we must be vigilant and accept one another regardless of features and color of skin on the basis of “content of character.” I can see an America fulfilling her promising destiny as a nation by revitalizing her commitment to honor the spirit and letter of the U.S. Constitution which ensures life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness of every American regardless of race or creed, a principle we too often wink at. It is not too late. It is never too late to heal, to find a cure.

What have we learned about racism? We’ve lived with it long enough. We know it’s costly in terms of life and property. Racial hatred is putting us in debt, morally and economically. Love is more cost-effective—if you want to look at it that way. This being a business-oriented society, that’s something to consider. But what have we really learned? Nothing? Does that mean we are going to continue to dangle in front of the oppressed the perennial carrot-on-a-stick, promises to make things better without any intention of following through in a stratagem of convenient duplicity? Or have we learned something over the centuries? Like ameliorating our attitudes which now require a fundamental change? A change of attitude that says, with an embrace, “hale fellow well met “ in the best sense of the word.

It would do wonders for the country—and the world—if we’re not already too far gone.

I have learned from racism and the concentration camps perseverance and hope. I have faith in America, the land of my birth. America is full of warts—recent events point to it—but the promise of America far outweighs any personal hardships, and I, for one, am willing to fight for the future of my country and the world. What can one man do? Put one’s best thoughts to a solution of the problem in the full belief that the vision expressed in our constitution is never out of reach but encourages every citizen to put one’s shoulder to the load of answering our nation’s endemic problems—in this instance, racism. Wage a war against racism, conquer it—and everything else will fall into place.

For me, the concentration camps were a blessing in disguise. They made me into a man at the age of nine. True, it has been a long road, but they forced me to question my identity as an American, marshal my thinking around defining myself and help me develop a personal philosophy and outlook on life which are indispensable for a writer.

All in all, the concentration camps and their experience enabled me to define myself as a person and man in a milieu that encompasses my life which has been lived as an American, not a Japanese or foreigner. I was in danger of becoming one because of my long sojourn in postwar Japan, growing up there into adulthood. Sticking to my guns, keeping the faith and fighting the good fight, I remained an American and proudly am one. I had no other choice, except to embrace the land of my birth. It’s been a long, rocky road, but I survived.

© 2020 Robert H. Kono