With a new sense of confidence, Iyenaga became more aggressive in negotiating his contract renewals with the University of Chicago and made the following demands: “that between Oct 1st and June 23rd each year the University shall have exclusive control of my time, with the annual salary of $3000. I beg, however, to attach to this acceptance, the following reservation to wit: that the University will commission me this year, or the next, to visit for the period of three months or so, Japan, Corea and Manchuria in order to study the recent conditions therein, the University defraying the travelling expenses amounting to $666, payable at anytime the University sees fit … it is the special commission and is undertaken for the interest of the University.”1 Despite this assertion, Iyenaga’s special request was not accepted by President Harper.2

In fact, soon after Iyenaga started working at the University of Chicago, “in 1904, the public’s enthusiasm for the lecture courses [was] beginning to wane, [and] the financial situation was desperate.”3 And yet, when the Russo-Japanese war broke out in 1904 and Japan’s unexpected victory brought about a historical turnover, Americans became even more interested in the Far East and Iyenaga’s work continued. In the year of 1906-1907, Iyenaga’s lectures covered even more popular subjects, among them “Bushido: The Soul of Japan” and “Women of Japan (illustrated with colored slides)”4 to please the growing audiences.

In February 1906, Japanese Consul Shimizu invited Professor John Wigmore, of Northwestern University Law School, and Iyenaga to a luncheon at the University Club.5 Wigmore had been invited to Japan by Yukichi Fukuzawa and had taught law for two years at Keio University in Tokyo, from 1890-1892. So, in fact, Wigmore and Iyenaga had once been colleagues at Keio University. Although Iyenaga was always on the move for his lecture tours and therefore did not spend much time in Chicago,6 his contact with the Japanese government naturally resumed.

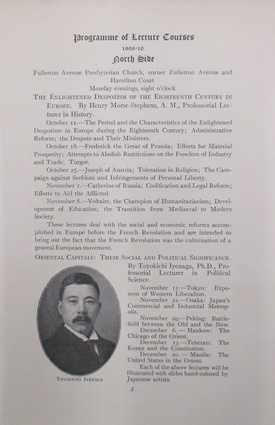

Iyenaga had been patiently waiting for his chance to travel to Asia. Further evidence of his ties to the Japanese government was his trip to Manchuria, China, and Hong Kong in January 1908, after he was granted a one-year sabbatical from the University of Chicago and returned to Japan for the first time in six years. The trip was funded by the South Manchurian Railroad, which was headed by Shimpei Goto, Iyenaga’s old boss in Formosa. Iyenaga probably approached Goto with his request to travel to Manchuria, just as he had approached President Harper three years prior, because the Manchurian trip appears to have been approved before his voyage to Japan. Assuming that his trip to Asia would be reflected in new lectures, the University of Chicago announced Iyenaga’s sabbatical and the content of his upcoming lectures as follows: “Dr. Iyenaga will leave for the Orient not later than January 1, 1908, where he will spend several months in travel and study in the preparation of new courses of lectures. He will return to America Oct 1, 1908, with a finely illustrated new course on “Oriental Capitals.”7

After returning to Japan from Manchuria, Iyenaga visited his former employer, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tokyo, and appealed to them about the necessity of educating Americans about the actual circumstances in Japan and Manchuria, in order to improve the U.S.-Japan relationship. He made the appeal in hopes of securing a subsidy for himself,8 as he had remarried and in order to bring his wife, Yui, to the U.S., he needed financial stability. His request was accepted and he was granted an annual subsidy of three thousand yen from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and one thousand yen from the Southern Manchurian Railroad. To provide a sense of the size of these subsidies, it should be noted that three thousand yen was equal to the annual remuneration for a member of the Diet in 1920.9

Iyenaga returned to the U.S. at the end of March in 1909, visited Japanese ambassador Kogoro Takahira in New York, and told him that, following the intentions of Foreign Affairs Minister Komura, he would work to promote U.S.-Japan relations.10 Back in Chicago, Iyenaga returned to his lecture work. His subjects at this time focused on Asian capital cities such as Mukden and Teheran, as well as Tokyo and Peking, which reflected the results of his research during his recent travels very well.11 The Chicago Tribune covered his lectures in articles such as “Hankow, the Chicago of the Orient”12 and “Jap Scholar Explains Koran.”13

Meanwhile, the Japanese government tried to influence public opinion in the U.S., after the San Francisco Board of Education passed a resolution to segregate the Chinese, Japanese, and Korean children from other non-Asian children in October 1906. In New York, a public opinion influence agency, the Oriental Information Bureau, was established in August 1909.14 To satisfy the Japanese government’s heightened expectations for his activities and successes, Iyenaga sent all of his lecture schedules and newspaper articles on his lectures to Tokyo.

Feeling uneasy about his future as travelling lecturer, Iyenaga wrote to Minister Komura in Foreign Affairs and requested employment in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He said that “Although I have no cause for repenting the work I have done in this country, I now greatly regret that I have pursued too long an independent course of life, and have kept myself too long out of touch with my country men. My field of usefulness seems to lie in the work of interpreting Japan to America, and America to Japan; to act as an intermediary between the two…I have hitherto estranged myself too much from the national current. It is therefore my present earnest solicitude to bring myself into closer touch with my country and thus join hands in the concerted activity of the nation.”15

Around this time, anti-Asian sentiment was growing: a Chicago Daily Tribune article appeared, warning of a “Yellow Peril,” using the examples of a Chinese student winning an oratory contest at Yale University and Iyenaga’s oratory success at Oberlin College twenty years earlier to make its case about the dangers of “orientals.”16 The political atmosphere in which he gave his lectureswas certainly worsening and Iyenaga was feeling “the heavy responsibility laid upon me,” as the recipient of a generous subsidy from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Iyenaga reported to his supervisor in Tokyo that “the opportunities to appeal to the American audiences, in other words, the demands for my lectures are far smaller than in former years. The only thing I can vouch is that I shall do my best.”17

While Iyenaga was desperately securing his financial situation, in 1910, Iyenaga’s wife, Yui, enrolled in the College of Education at University of Chicago.18 In order to increase his lecture opportunities, Iyenaga also worked for the American Society for the Extension of University Teaching.19 At this point Iyenaga had to admit that opportunities were dwindling, “I regret to say the demand for lectures on the Far Eastern Affairs by the American Public is small. I have no bright prospect.”20

Soon thereafter, his concerns became a reality. In August 1911, he received a notice that “after this year it is the plan of the University discontinue the Lecture-Study work except the activities of University Lecture Association.”21 Later that year, the department closed. “After 1911 lectures were given in and around Chicago under the auspices of the University Lecture Association (which continued until 1923). Different from the early offerings of the Association, the later lectures were of a strictly popular character and there were no classes or written exercised connected with them.”22

With the political climate changing, Iyenaga, who received monetary support from the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, did not dare to continue giving his entertaining lectures for the University Lecture Association. After his contract with the University of Chicago expired, Iyenaga stayed in Chicago until the end of 1911 and became active in voicing his opinions at various venues and publications. When an editorial in the Chicago Tribune, “Japan and the Chinese Rebellion,” criticized the policy of Japanese government as follows: “the Japanese endeavor to belittle the Chinese movement for more popular forms of government by referring to the revolutionists as “rioters,” Iyenaga made the following response: “it is clearly the duty of foreigners to be neutral, to stand completely aloof, in the present strife” and “Japan is, I am confident, anxious to steer her course clear from the shoals and rocks that will lie under the whirlpool of foreign intervention.”23 At a regular meeting of the Japanese Club at University of Chicago, Iyenaga lectured in fluent English on “Japanese management in South Manchuria.” Audience members included Consul Yamasaki and Mrs. Yamasaki, Kiyoshi Kawakami, and Jyuji Kasai, both of whom were later labeled Japanese propagandists by Flowers.24

After an eight-year affiliation with the University of Chicago, Iyenaga moved to New York in January 1912. The Japanese Club at the University of Chicago valued Iyenaga’s contributions so much that it named Mr. and Mrs. Iyenaga as honorary members.25 In New York, Iyenaga took a job as managing director for a public opinion media outlet, whose goal was to educate Americans about Japan at the East and West News Bureau in New York, which the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs had established in 1913.26 Iyenaga’s reputation as a lecturer with the capacity to move Americans was so widespread that Ambassador Sutemi Chinda reported to Minister Makino in Tokyo, “everybody admits that Iyenaga has peculiar skill to move Americans.”27

Although he left his mark in U.S. history as a Japanese propagandist, Iyenaga, the individual and immigrant, called the U.S. his second home and left the following words behind:

“I have ceased for a long time to be annoyed by any manifestation of race prejudice toward me among Americans, high or low, old or young.”28

“[in dealing with the American people] study with care their temperament and idiosyncrasies. Learn assiduously their language, ways and modes of thought. Appreciate their great and good part and they will not fail to reciprocate. Do your best to make known to them Japan and the Japanese, for the vast majority of the Americans are quite ignorant of your thoughts, ideals and conditions. … Lend no ears to whispers of calumny and suspicion.29

“I need hardly emphasize, in breaking down the insular spirit that has long chained our Island Empire, and riding abreast on the wave of cosmopolitanism which is happily the very spirit pervading the land, wherein we make our present abodes.”30

Even today, almost eighty five years after his death in 1936 in Oneida, New York,31 Iyenaga’s words still resonate in this author’s ears, a Shin Issei who grew up immersed in the pre-war Japanese values of parents who experienced B-29 bombings and Japan’s defeat. Everything changed with World War II. I wonder: in our current complicated postwar racial and global situation, could a talented individual like Iyenaga, produce “English language with oratorical fluency,” and take the Shin Issei beyond the shame of Japan’s defeat, which he never knew?

Notes:

1. Iyenaga’s letter to Harper dated December 25 1904, Office of the President, Harper, Judson and Burton Administration Records, Box 53 Folder 18, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

2. Harper’s letter to Iyenaga dated December 28 1904, Office of the President, Harper, Judson and Burton Administration Records, Box 53 Folder 18, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

3. University Extension at the University of Chicago 1892-1930, page 26

4. Bulletin of Information 1906-1907, The University Extension Division, Lecture-Study Department

5. Shimizu’ letter to Wigmore dated January 29 and February 7 1906, Wigmore Collection, Box 105, Folder 10, Northwestern University Archive

6. Nichibei Shuho, March 10, 1906

7. Bulletin of Information 1907-1908, The University Extension Division, Lecture-Study Department

8. Ota, Masao, “Shikago Daigaku to University Extension: Iyenga Toyokichi no Katsuyaku,” ANNALS, St. Andrew’s University Research Institute for Education, Vol 5, 1996, page 36

9. Ibid

10. Takahira’s letter to Komura dated April 8, 1909, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 1-1-3-8-001

11. Bulletin of Information 1910-1911, The University Extension Division Lecture-Study Department

12. Chicago Tribune, December 5, 1909

13. Chicago Tribune, December 16, 1909

14. Ishii, Hiroshi, “Dai-Ichi-ji Taisen-Ki no Kawakami Kiyoshi no Katsudo,” Shigaku Zasshi, Vol 6, 2005, page 61

15. Iyenaga’s letter to Komura and Kurachi dated November 23, 1909

16. Chicago Daily Tribune, December 30, 1909

17. Iyenaga’s letter to Kurachi dated June 10, 1910

18. Annual Register 1910-1911, University of Chicago

19. Iyenaga’s letter to Kurachi dated December 28, 1910

20. Iyenaga’s letter to Kurachi dated April 5, 1911

21. Letter to Iyenaga dated August 9, 1911

22. University Extension at the University of Chicago 1892-1930, page 30

23. Chicago Tribune, October 24, 1911

24. Nichibei Shuho, November 18, 1911

25. Cap & Gown 1912, page 122

26. Makino’s letter to Chinda dated August 22, 1913

27. Chinda’s letter to Makino dated September 27, 1913

28. Iyenaga, Toyokichi, “Experiences of A Japanese in America,” Russel, Lindsay, Ed., America to Japan: A Symposium of Papers by Representative Citizens of the United States on the relations between Japan and America and on the Common Interests of the Two Countries, page 254

29. Iyenaga, page 258

30. Japanese American Commercial Weekly, January 4, 1913

31. Chicago Tribune, December 30, 1936

© 2021 Takako Day