The owner of the Asian Japanese youth is also a New Christian.

Looking back, it is highly likely that the owner of the young Japanese man who was sold as a slave in Argentina in 1596, the subject of my column "Uncovering the Mystery of Japanese Slaves," was also a "New Christian."

Tetsuzo Oshiro, an Argentine immigrant who was the first to write in detail about this case, wrote in his book "Córdoba" that "there is strong evidence that the young Japanese man named Francisco Japón was brought to Japan by the Nanban people (Portuguese), with whom trade with Japan was frequent at the time. It can also be surmised that he entered the port of Buenos Aires without taking the official Spanish shipping route. This means that, according to Spanish national law, he was not eligible to be treated as a slave" (page 15).

The Portuguese merchant that Oshiro describes as a "slave trader" was named Diego Lópes de Lisboa. Upon investigation, it turns out that Diego was quite a famous person.

In Spain, the Inquisition began in 1478, which led to the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. This was followed by Portugal, which saw the introduction of forced conversion orders in 1497 and the Inquisition in 1536, which led to a rapid increase in the number of New Christians.

In "History of Portugal" (Albert-Alain Bourdon, Hakusuisha, 1979, pp. 59-60), it is written: "Despite the intention of the Papacy to tacitly approve, a national religious inquisition was created in 1536, and came to wield absolute power through a system of informants, secret trials, and the fear of burning at the stake... The actions of the religious inquisition were not as bloody as one might imagine, but the number of 1,454 victims (out of 24,522 trials recorded over two centuries) seems too low considering the social conditions of the time, when secrecy, informants, violence, etc. violated individual freedom and stagnated literature and science."

In other words, the Age of Discovery began at a time when persecution of the Jews was intensifying in the Iberian Peninsula. As religious oppression intensified in Europe, a certain portion of the new Christians took the initiative to emigrate to the New World, where there was less surveillance. One of these Portuguese immigrant merchants was Diego Loppes de Lisboa.

Diego's father was burned to death during the Inquisition

Diego's son, Juan Rodrigues de Leon Pinero (1590-1644), is famous for having studied theology at the University of San Marcos in Lima and becoming a priest of Jewish origin. Looking at his background, his paternal grandfather (Diego's father), Juan Lopez de Moreira, was publicly burned to death in Lisbon in 1604 after his origins were questioned by the Inquisition.

That is, Diego, who owned the Japanese Francisco Japon in Argentina, whose father was a secret Jew who was burned to death during the Inquisition.

Furthermore, the research booklet "La Palabra Israelita VIERNES 7 DE ENERO DE 2005" (translated as "Words of Israel", January 7, 2005 issue) of the Center for Jewish Studies of the University of Chile, page 12, states that Diego himself was always suspected of being Jewish, so he studied theology and was ordained as a priest in 1628, in order to clear the suspicion that he was a New Christian.

The University of Chile's Los «Portugueses» en el Nuevo Mundo (Cuaderno Judaico no 23) also contains a description of such a family.

"The Portuguese "New Christian" Diego Lopez fled with his family to Spain to avoid the same fate as his father, who was burned to death as a Jew, at the same time that the two kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula were being unified. It seems that he was fleeing the Inquisition, but Diego Lopez set off for India, first passing through Brazil, and then on to La Plata, where he settled in Buenos Aires in 1594. The following year he moved to Cordoba, where he spent several years. In 1604 he summoned his family to Buenos Aires, and with a letter of credence from the royal family of Madrid, a "blood purification" certificate of faith, he was able to safely pass the Inquisition in Buenos Aires in 1603."

It was a time when people felt in danger just for being suspected of being Jewish. Francisco Japon was sold to the priest the year after Diego came to Cordoba.

So in Brazil too?

Francisco Japon was brought to Argentina by a Portuguese New Christian merchant. This merchant had also lived in Brazil before coming to Argentina. It is highly likely that there were other Japanese people like him in Argentina, and it would not be surprising if there were other young Japanese people who came to Brazil with similar motives and routes. Rather, it is more reasonable to assume that there were.

In the second half of the 16th century, sugar cane cultivation and sugar factories began to be operated on a large scale in Bahia and Pernambuco in Brazil, and aristocrats and wealthy people with large capital arrived there. It is well known that many of these people were "New Christians" who had escaped persecution in Portugal and Spain. There may have been Japanese slaves among their servants.

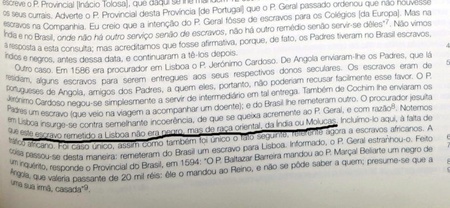

When I consulted a Brazilian historian, he introduced me to "Serafim Leite - Historia de Companhia de Jesuita no Brasil." It is a large-scale work written by Portuguese Jesuit historian Father Serafim Leite (1890-1969), which is a collection of letters exchanged between Jesuit priests in Brazil and the Society of Jesus in Brazil between 1538 and 1563, and which unravels the history of the Jesuits in Brazil as uncovered through these letters.

Although I only looked at a part of it, it contained some interesting information. It states that black slaves brought by colonists had been working in Brazil even before the Jesuits arrived in 1549, and that "the locals believe that one black slave does the work of four Indians," "4,500 black slaves were brought to Brazil before 1528 alone," and "When there was a shortage of African slaves, Oriental peoples, Indians, and Moroccans were sent to Lisbon" (Volume 1, page 333). The possibility that Oriental slaves were also in Brazil cannot be ruled out.

Furthermore, since the early Brazilian colony only had missionaries and a small number of colonists, there are sections containing requests such as, "We don't have enough women. Please send more orphans," so it is not impossible that orphans of Japanese slaves were sent from Lisbon.

I would like to see a researcher come forward to investigate the possibility that Japanese slaves were brought to Brazil around 1600.

*This article is reprinted from the Nikkei Shimbun (October 20, 2020).

© 2020 Masayuki Fukasawa / Nikkey Shimbun