Introduction: Chautauqua

“Know Japan! Understand Japan!” Educating Americans about Japan was one of the most important roles assigned to Japanese immigrants, especially for those who were college graduates, equipped with near-native English fluency, and had arrived in the U.S. over 120 years ago. Their strong will and zeal, which enabled them to become professional lecturers and to stand up before crowds of strangers and give speeches on Japan and the Japanese, must have been unimaginably grand in those days, compared to our current computer controlled age, when so much information can circulate instantly to all points of the world. To this author, they were a rarified breed, because these days, lecturing on Japan and Japanese culture or history seems to be limited to authorized celebrities or specialists, who are officially invited by Americans and sent by well-known Japanese public agencies or consulate-related personnel and agencies.

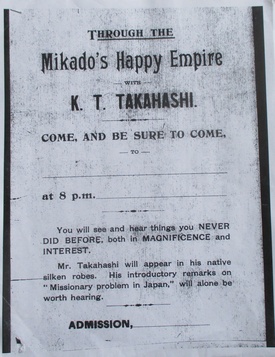

One good example of an early Japanese immigrant who widely educated Americans about his home country was Kadzutomo T. Takahashi, who graduated from the University of Michigan Law School in 18861 and began delivering illustrated lectures called “Through the Mikado’s Happy Empire” in Montreal, Canada. He wore kimono while lecturing and used 120 stereopticon slides, which he imported from Japan, to introduce his country.2 Takahashi was advertised as “the only Japanese lecturer in America who speaks the English language with oratorical fluency” and it was said that he provided “highly interesting and instructive entertainment.”3

Those pre-war Japanese immigrants, who could speak the English language “with oratorical fluency,” were warmly welcomed in American society. The Chicago census contains records of several “lecturers”; Takaze Fukashina in 1910, Naojiro Kimura in 1920, and Anton Ishida in 1920 and 1930.

Yasuhiko Niimura, an art school student, reported that he found an interesting Japanese guest staying at the Japanese Young Men’s Christian Institute in Chicago around 1916. According to Niimura, the guest was not a minister, but he visited various churches to preach in haori and hakama (traditional Japanese men’s clothing) and lived on the gratuities he collected from his lectures. Though the subjects he “preached” about are unknown, Niimura noted, “of course his English was very good.”4

However, the popularity of these lecturers must be contrasted with the heightening distrust and deepening tensions between the U.S. and Japan at that time. As such, the lecturers’ sense of mission must have been directly connected with their survival as Japanese nationals, living in the U.S. But there were Americans who considered these lecturers to be a threat. One anti-Japanese agitator, Montaville Flowers, a well-known journalist5 and president of the International Lyceum Association of America, headquartered at 122 South Michigan Avenue in Chicago,6 made a list of five Japanese in the U.S. that he considered to be Japanese propagandists. The men on his list were Kiyoshi K. Kawakami, Toyokichi Iyenaga, Jyuji G. Kasai, Kiyosue Inui, and Yamato Ichihashi.7 With the exception of Ichihashi, their oratorical skills had come to fruition in the Midwest. Could this have been due, even remotely, to the unique social climate of the Midwest, which gave birth to an early 20th century phenomenon known as the Circuit Chautauqua?

Circuit Chautauqua was an educational and social movement, aimed at adult audiences, that featured diverse speakers, lecturers, and performers. It was first introduced in Iowa in 1904, and within ten years, became a very popular summer event throughout the country. “The Circuit Chautauqua programs exposed countless Americans to many new ideas and customs, national and international issues, and popular forms of entertainment that otherwise would have been inaccessible to them.”8

The roster of talents included not only Americans; Japanese speakers were also given a chance to perform in various events in the Chautauqua circuit. For example, in the 1910s, Michitaro Ongawa toured the country with his American wife and introduced the U.S. to Japanese dance and music.9 Kijuro Shidehara, Japanese ambassador and Japanese representative at the Washington Naval Conference in 1921, made a speech “to promote “honorable paths of peace” at the Twentieth Lecturers Conference on Public Opinions and World Peace, held by The International Lyceum and Chautauqua Association at the Drake Hotel in Chicago from September 13-19, 1922.10

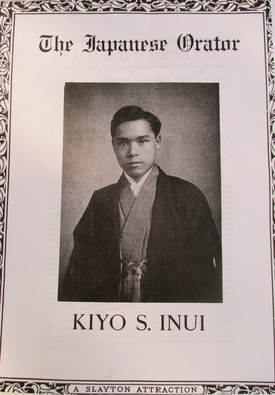

Tamaki Miura, the first world-renowned, female Japanese opera singer, was scheduled to hold a concert in the small town of Lincoln, Illinois on August 29, 1926.11 “Circuit Chautauqua programs prior to 1917 were dominated by the platform lecture feature,”12 and there were two well-known Japanese orators: Kiyo Sue Inui, one of the five Japanese propagandists Flowers had listed, and Yutaka Minakuchi.

Kiyo Inui, born in Shikoku in 1884, came to the U.S. to study at the University of Michigan in 1902.13 He was given the nickname “Silver Tongue” in his student days,14 as he won several oratorical contests in 1905 and 1906, and was “much in demand as a lecturer, having appeared at several Chautauqua assemblies during summer in 1905 and before lecture associations during the winter season.”15

As the Michigan representative, he won first honors with a speech titled “The Mission of New Japan” at the annual contest of the Northern Oratorical League, held under the auspices of Oberlin College, on May 4, 1906.16 After graduating from the University of Michigan in 1906, Inui moved to Detroit and continued his lectures. The promotional materials for his lectures show that he was managed by at least three entities, A. Slayton Attractions, The Mutual Lyceum Bureau in Chicago, and The Scorer Lyceum Bureau in Philadelphia.17

When the Redpath-Slayton Lyceum Bureau managed him, Inui travelled by train from the Midwest to the East and South. His lecture titles were “The Sick Man of Asia and His Doctors,” “Japanese Progress,” and “An Illustrated Lecture on Japan.”18 Right after Thanksgiving in 1913, Inui appeared in Chicago and was invited to a dinner party given by the First Baptist Church, attended by more than one hundred Japanese.19 Inui made a table speech claiming that “a Japanese war scare came around annually like Christmas and New Year’s and generally at the time the government at Washington was trying to put through congress the budget for the navy, but he declared that the two nations are steadily coming closer, commercially, politically, and religiously.”20

War talk came back at a luncheon lecture held at the City Club of Chicago on September 4, 1914. Inui told the audience that “there is more possibility of an American invasion of Japan, especially since the building of Panama Canal, than of Japan’s jumping over seven thousand miles to invade the Pacific coast.”21 He advocated for peace in his lectures.

Yutaka Minakuchi, born in Okayama in 1879, was a Christian who came to the U.S. in 1897 to study at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, Kentucky.22

After receiving his Masters of Arts degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1910 and serving as a pastor for the next three years in Ashville, North Carolina, he began lecturing in the Chautauqua circuit around 191323 because he desired “to create greater interest in missionary needs in the far east.”24

His original purpose in coming to the U.S., “to interest the people in the welfare of Japan”25 only got stronger as time went by. When Minakuchi, a religious speaker, came to Chicago on April 13, 1913, he was the first Japanese ever to give the principal address at the Sunday Evening Club in Chicago. He was referred to as Reverend Minakuchi, a “noted Japanese evangelist,” and the title of his address was “The Vital Needs of the Age.” In his address, he claimed that “American ideals are too mercenary” and that “the whole world needs social rejuvenation.”26

In the summer of 1915, Minakuchi had over eighty lecture engagements on one of the largest and oldest Chautauqua circuits of the West, and a similar number of speaking engagements in the summer of 1916.27 Minakuchi returned to Chicago in 1918 under contract with the Ellison-White Chautauqua System of Portland, Oregon.28 One of his main lecture subjects was “The Border Land,” in which he advocated for “where [there] is no East nor West, but where one fades into the earth in common understanding.”29

In March 1921, Minakuchi again lectured in Chicago, on the theme of “American-Japanese Relations,” and told the audience that “the United States need fear no war with Japan [because] Japan is not able to finance a war” and that “the Hawaiian islands are not for white men but for colored.” In response, an editorial in the Chicago Tribune commented that “What Dr. Minakuchi unconsciously reveals is the expansive spirit of the Japanese people.”30 Minakuchi spent half his life as an orator with a strong Chicago connection, and travelled extensively in the 1930s giving lectures under the auspices of the Adult Education Council of Chicago.31

However, long before Inui and Minakuchi became lecturing successes, there had been another Japanese speaker who was seriously involved in the early Chautauqua movement in the 19th century. This was Toyokichi Iyenaga, whose talent as a propagandist for Japan was acknowledged by Flowers. Iyenaga began his career as a travelling lecturer while a student at Johns Hopkins University, in part because “it was Chautauqua which led to the introduction of the university extension movement.”32

The University Extension Program, which offered classes to educate local residents in community settings, started in Britain in the 1860s. It “was transplanted to America and grew rapidly in the eighties and nineties. The system was first presented in 1887 by Dr. Herbert B. Adams of Johns Hopkins University.”33 Dr. Adams, a historian, and Richard T. Ely, a political economist, vigorously promoted the University Extension Program at Johns Hopkins University. Iyenaga, a new graduate student looking for opportunities, was naturally eager to get involved with the University Extension Program. 34 In 1890, Iyenaga earned a Ph. D from Johns Hopkins University with his thesis, “The Constitutional Development of Japan from 1853 to 1881,” with help from Dr. Adams, who loaned Iyenaga the money to help him finish his education.35

The summer after graduation, Iyenaga “delivered lectures at Chautauqua (in New York State) and other places,” toured as far as Madison, Wisconsin, and, according to reports, pleased his audiences.36 Iyenaga went home to Japan in the fall of 1890, but ten years later, he returned to the U.S., as if he sensed a promising future for Chautauqua, “the origin of such educational methods as the new Chicago University is adopting.”37

2. The University of Chicago Extension Program

In 1890, William Rainey Harper, president of the newly-founded University of Chicago, invited Dr. Herbert B. Adams and Professor Richard Ely of Johns Hopkins University to join the University of Chicago faculty. Richard Ely and William Harper had both worked at the New York Chautauqua Institute, “the first permanent Chautauqua, an important vehicle for adult education in America,”38 and knew each other very well.39

President Harper had been a member of the advisory committee of the American Society for the Extension of University Teaching during his Yale days, and was “familiar with both movements (the English extension movement and the popular American Chautauqua courses). Harper pioneered in instruction by correspondence.”40 Ely and Harper were comrades who shared their excitement about the mission of the extension movement, which had the potential to bring a university education to all classes of society through lifelong learning.

Ely responded to Harper, “we are thinking seriously about this matter. If we should go to Chicago, we should expect to give all our energy to build up the institution.”41 In the end, Ely declined the invitation from Harper, explaining that ”I think the time has come for me to withdraw from popular work. I thoroughly believe in popular work, and am still prepared to assist it in every way,”42 and took a job at University of Wisconsin, Madison in 1892 instead.

The University of Chicago opened in October 1892 and included a Division of University Extension. The Extension was divided into six departments, and one of them was the Lecture-Study department. The Lecture-Study department started with 67 classrooms in various buildings and locations, with 124 lectures; the average attendance at these lectures was 27,000 in 1892, but the department grew to 140 centers, 190 lectures, with an average attendance of 36,000 attendees at lectures by 1901.43

Notes:

1. Announcement with List of Students, Department of Law, University of Michigan 1885-86, page 26

2. Japan through Western Eyes: Records of Traders, Travellers, Missionaries and Diplomats, 1853-1941, Part 3: The William Griffis Collection from Rutgers University Library, Correspondence and Scrapbooks, Reel 37

3. Ibid

4. Ito, Kazuo, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-Shi, page 165

5. Chang, Gordon H, Morning Glory, Evening Shadow, page 39

6. The Luyceunite and Talent, September 1912

7. Chang, Gordon H, page 39

8. Tapia, John E, Circuit Chautauqua, page 7

9. Takako Day, “Michitaro Ongawa: The First Japanese American Chicagoan - Part 1” Discover Nikkei, December 7, 2016.

10. The Lyceum Magazine July 1922.

11. Redpath Chautauqua Collection Series VIII, talent Schedule MSC 150 Box 14, Special Collection, University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City, Iowa

12. Tapia, page 53

13. Honor Orations in the Contests of the University of Michigan Oratorical Association 1915, page 178

14. Chicago Tribune, March 17, 1906

15. Honor Orations in the Contests of the University of Michigan Oratorical Association, 1915, page 178

16. Chicago Tribune, March 17 and May 5, 1906

17. Redpath Chautauqua Collection, Special Collection Department, University of Iowa Libraries

18. Ibid

19. Nichibei Shuho, January 31, 1914

20. The Chicago Tribune, November 29, 1913

21. The City Club Bulletin, December 2, 1914

22. Washington, Passengers and Crew List

23. “Yutaka Minakuchi: A Story in a Name,” Pack Memorial Library, December 9, 2013.

24. Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1913

25. Chicago Tribune, April 14, 1913

26. Chicago Daily Press, April 14, 1913

27. Redpath Chautauqua Collection, University of Iowa Libraries,

28. World War I registration

29. Redpath Chautauqua Collection, University of Iowa Libraries,

30. Chicago Tribune, March 1, 1921

31. “The Story of a Japanese Minister Living in Glover, Vermont During WW II” Glover History, Winter 2003, Vol 12, No. 1.

32. Cosmopolitan, 1895, page 252

33. University Extension at the University of Chicago 1892-1930, page 1, The University of Chicago University Extension Records 1892-1979, Special Collection, University of Chicago

34. Ota, Masao, “Iyenaga Toyokichi and University Extension,” ANNALS, St. Andrew’s University Research Institute for Education, No 1, 1992, page 3

35. Ely’s letter to Iyenaga dated May 15, 1902, Richard T Ely Papers, Box 21 Folder 5, Wisconsin Historical Society Archives

36. Ely’s letter to Iyenaga dated January 8, 1901, Box 18, Folder 1, Iyenaga’s letter to JB Pond dated July 3, 1901, Richard T Ely Papers, Box 19, Folder 6,

37. Cosmopolitan, 1895, page 252

38. Tapia, page 8

39. Ely’s letter to Harper dated December 21, 1891, Office of the President, Harper, Judson and Burton Administration Records, Box 42 Folder 9, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

40. University Extension at the University of Chicago, 1892-1930, page 20

41. Ely’s letter to Harper dated November 15, 1890, University of Chicago

42. Ely’s letter to Harper dated December 21, 1891, University of Chicago

43. University Extension at the University of Chicago, 1892-1930, page 98

© 2021 Takako Day