Numerous authors have previously uncovered the stories of the outside supporters who vocalized their support for Japanese American communities amidst the wave of anti-Japanese vitriol on the West Coast in early 1942. Although the community of supporters ranged from leftist activists to New Deal idealists, it was a small minority of religious figures who agreed on the moral repugnance of Executive Order 9066 and mobilized to assist Japanese Americans during the ensuing incarceration.

One of the most unique personalities among those individuals who spoke out on behalf of Japanese Americans is Ronald Lane Latimer, a Buddhist priest. Latimer lived several lives. In his early career, Latimer distinguished himself as a publisher, one who befriended famous poets such as Wallace Stevens and helped popularize the Modernist literary movement in the United States. Later, he converted to Buddhism, and, along with Reverends Julius Goldwater and Sunya Pratt, he became one of the few non-Japanese Buddhist priests in the United States. In his later years, he abandoned Buddhism and withdrew from public life.

Ronald Lane Latimer was originally born James Leippert in Kingstown, New York, on October 27, 1909, the son of a German immigrant family. He grew up in a middle-class, Catholic household. Already a talented writer from an early age, Leippert enrolled in Columbia University as part of the class of 1933. While at Columbia, James Leippert (also known as “Jay”) immersed himself in various literary circles. He joined the Columbia’s literary group The Philolexian Society, and swiftly became a board member of the group. His ascent in the leadership of the Society’s publication The Philolexian-Varsity Review also generated controversy, as a power struggled developed between him and another student member.

At one point, Leippert founded two independent literary magazines—The Lion and Crown and The New Broom and Morningside—that drew criticism as competing with the The Philolexian-Varsity Review and as a means of leveraging himself to the presidency. Eventually, Leippert established himself as president of The Philolexian Society. By the end of his college career, Leippert established himself as an ambitious publisher, printing the works of such authors as Gertrude Stein, Conrad Aiken, and Erskine Caldwell. While at Columbia, Leippert established a friendship with the rising poet Wallace Stevens. In 1934, Leippert changed his name to Ronald Lane Latimer, a moniker that he would keep for the rest of his life, and embarked on a literary career.

In her 2013 article for the Poetry Foundation—the organization tasked with preserving and promoting American poetic traditions—journalist Ruth Graham described Latimer as “a remarkably shadowy figure, little known even to fans and scholars of the poets he influenced.” Nonetheless, much of Latimer’s literary career has been illuminated by the work of scholar Al Filreis.

From 1934 to 1938, Latimer and Stevens corresponded regularly on topics related to poetry and publishing. Latimer encouraged Stevens to contribute his poetry to Latimer’s journal Alcestis Quarterly, which he founded in 1934. Canadian writer Tim Bowling argues that Latimer’s Alcestis Quarterly provided Stevens with one of his first platforms for sharing poetry. Indeed, Stevens provided a number of his poems for the Alcestis Quarterly, and Latimer published two sets of Stevens’s poems—Ideas of Order in 1935 and Owl’s Clover in 1936—in limited edition volumes.

Along with Stevens, William Carlos Williams frequently collaborated with Latimer on poetry volumes. Latimer authored the introductions to two of Williams’s poetry volumes, An Early Martyr in 1935 and Adam & Eve In the City in 1936, and released both with his publishing group Alcestis Press. In addition to his correspondence with Stevens, Latimer also maintained a steady correspondence with Williams, Ezra Pound, Erskine Caldwell, and filmmaker Willard Maas, and occasionally exchanged letters with Ernest Hemingway, Robert Frost, and T.S. Elliot. Scholar Al Filreis argues that Latimer, a bisexual man, also had an intimate relationship with Maas, who was known for his affairs outside his marriage to filmmaker Marie Menken. When Latimer founded Alcestis Quarterly in 1934, Maas assisted Latimer as an editor.

After Alcestis Quarterly folded in 1936, Latimer found himself adrift. Stevens consoled Latimer, telling him “giving up The Alcestis Press must be to you what giving up any idea of writing poetry would be to me.” When Latimer told Stevens his intentions to take the press to Mexico City, Stevens warned him the idea would fail. Instead, Stevens urged him to go elsewhere in the states, namely California.

Latimer later bequeathed the last of his literary projects to Stevens. Looking for a new life, Latimer decided to pursue a new career as a Buddhist priest. Latimer’s initial interest in Buddhism began during his study of Buddhism while a student at Columbia.

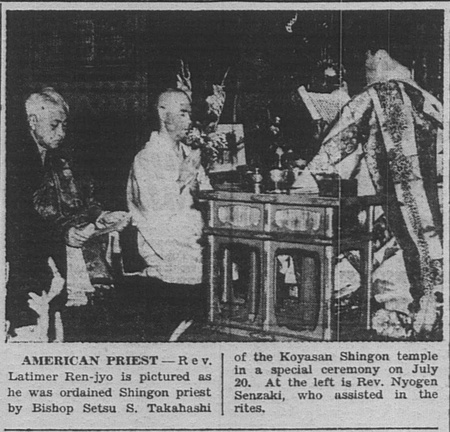

Latimer moved to Los Angeles in 1939, and began studying both Shingon and Zen Buddhism under the tutelage of Reverends Seytsu Takahashi and Nyogen Senzaki. The New World Sun reported that, on July 18, 1940, Reverends Takahashi and Senzaki ordained Latimer as a monk. As a priest, Reverend Latimer assumed the name “Latema Renjo,” and continued to live at the Koyasan Beikoku Betsuin.

A month after his ordination, on August 25, 1940, Latimer penned an article that appeared in the Rafu Shimpo and Kashu Mainichi Shinbun reflecting on his conversion. In devoting his life to Buddhism, Latimer confessed that “many old habits must be broke, many old friends are lost” as part of becoming a priest, but expressed no regrets as “feelings of unity and love and respect grows in a monk’s heart.”

On October 15, 1940, Latimer left for Japan, with the intention of entering a monastery. Unfortunately, U.S. authorities refused Latimer permission to board the ship for Japan, as the U.S. government banned exit visas on ships bound for East Asia. Latimer seems nonetheless to have secured passage to Japan, as the Kashu Mainichi soon after reported Latimer as studying in Kyoto and Koyasan.

Latimer returned to the United States on October 21, 1941, and lived briefly at the Miyako Hotel in Little Tokyo. Reverend Latimer did not immediately return to work at the Koyasan Temple, which sparked rumors that Latimer was avoiding the temple due to political reasons related to rising tensions between the U.S. and Japan. As a response to these rumors, the Rafu Shimpo published a statement written by Latimer on November 4, 1941, in which Latimer stated that “As a Buddhist priest, I have no interest in politics…I intend to continue my connections and work in Japanese Buddhism in the future, regardless of relations between Japan and America.”

Latimer then returned to Koyasan Buddhist Temple in Little Tokyo. While serving as a reverend at the Koyasan Buddhist Temple, Latimer took up the position of troop leader for temple’s Boy Scout Troop 379. As part of his ceremonial duties as a priest, Latimer helped Reverend Nyogen Senzaki to dedicate a 1200 year-old statue of Acalanatha, a deity figure in Buddhism, at the Hompa Hongwanji Betsuin. He also briefly taught courses on Buddhism at the Religious Studies department at the University of Southern California.

In early 1942, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of war, Reverend Latimer came forward to defend both the Japanese American community and the tenets of Buddhism. In February 1942, as the Koyasan Beikoku Betsuin renamed itself the “True Word Buddhist Church of America,” Reverend Latimer established a welfare department for the temple.

In the late afternoon of March 7, 1942, Reverend Latimer took the stand before the Tolan Committee at the State Building in Los Angeles. He surely believed that, as a white American, his voice would have more credibility and persuasiveness in official circles.

Initially, he described himself as “of American ancestry on both sides for about 150 years”—a false statement used to exaggerate his American identity. When asked by Congressman George H. Bender of Ohio whether the claim that Buddhists worshipped the Emperor of Japan was true, Latimer outright refuted the claim. In addition to noting that even in Japan, Buddhism was not a “state religion” as depicted by the West Coast press, Latimer emphatically stated that Buddhism in the United States is unique and separate from Japanese Buddhism.

Latimer even went so far as to state stated that Shintoism, although demonized by U.S. officials and racial zealots as the state religion of Japan, had been transformed by Japanese immigrants in the U.S., who had proceeded to “deify George Washington and Abraham Lincoln to make it appealing to the second generation of Japanese Americans.”

In his closing statements, Latimer argued that the government’s claim of “military necessity” for mass removal concealed a real truth of anti-Japanese prejudice, and urged the Tolan committee to provide financial relief and protection to Japanese American families who would be victimized by forced removal. Latimer’s statement was well-received among Japanese Americans, and was later quoted by Joe Kurihara in a speech given against the Manzanar Citizens Federation.

© 2021 Jonathan van Harmelen