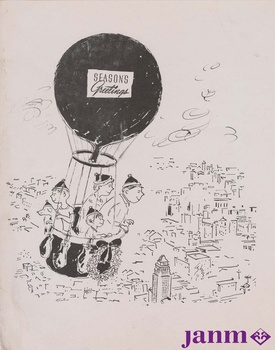

A whimsical drawing by Miné Okubo portrays a family and dog adrift in a hot air balloon over downtown Los Angeles, the distinctive city hall building in the foreground. The subject matter is very different from the camp drawings of Citizen 13660.

Okubo produced this sketch for the holiday edition of the Japanese American newspaper Kashu Mainichi sometime between 1965 and 1975. The drawing was part of a larger collection donated to the Japanese American National Museum in 1998 by Hiro Hishiki, Kashu Mainichi editor and publisher. The Los Angeles newspaper had a long prewar history of employing important writers, including Hisaye Yamamoto. In addition, Sei Fujii, Kashu Mainichi owner and publisher, helped overturn the Alien Land Law when he sued the State of California in the 1952 case Fujii v. California.

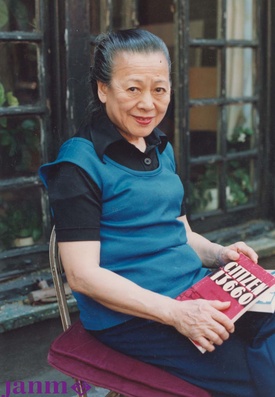

In commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the landmark publication of Okubo’s Citizen 13660, JANM is presenting a special exhibition, Miné Okubo’s Masterpiece: The Art of Citizen 13660. For the first time, the book’s artwork and its creative process are on display. The exhibition opened August 28, 2021 and is on view through February 20, 2022. A large photograph of Okubo sketching the camp barracks greets museum visitors. Two galleries feature original artwork from Citizen 13660—sketches, a sketchbook, and a draft of the final manuscript.

Collections Director and curator of the Okubo exhibition, Kristen Hayashi, and summer Getty intern, Rose Keiko Higa, found it difficult to select only 28 drawings out of the 198 book illustrations. Hayashi said, “She draws readers in through the seemingly easily understandable artwork and relatively short text, but if you take a closer look, the complexity that she layers in becomes quite apparent. The irony, tragedy, and injustice of the day-to-day is all there. We wanted visitors to be able to take a closer look at a selection of the original artwork and make their own observations.”1

At Tanforan temporary detention center and Topaz concentration camp, Okubo created hundreds of quick sketches and artwork, taught art classes, and oversaw artistic direction for three volumes of the Topaz art magazine Trek. She used her drawings not only to document her experiences, but also to communicate to friends outside of camp.

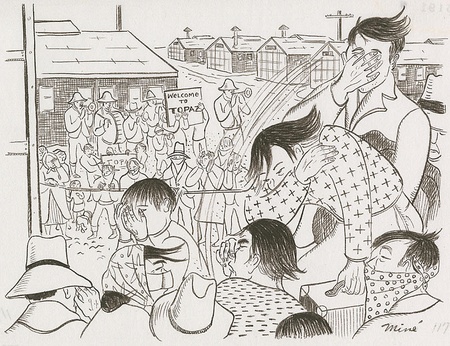

One of Hayashi’s favorite drawings is the arrival of Okubo and her brother to Topaz during a dust storm, since it depicts the irony of the situation so immediately. The illustration rhetorically asks how an inhospitable climate could be welcoming. The caption reads, “As we stepped out of the bus, we could hear band music and people cheering, but it was impossible to see anything through the dust.”2

The exhibition is drawn from the 2007 Okubo donation from the Estate of Miné Okubo which is in the museum collection. This large donation includes all Citizen 13660 drawings, an early annotated manuscript, charcoal and ink drawings, and paintings from the WWII period. It also includes around 150 postwar paintings from the late 1960s–1990s. JANM Senior Curator of Art from 1992 to 2006, Karin Higa (Rose Keiko Higa’s aunt) had the vision to persuade Okubo and her estate to donate the collection to JANM.

Okubo left Topaz in 1944 after Fortune magazine in New York hired her to illustrate a special edition of Japan. They had seen some of her artwork in Trek and petitioned for her early release from camp. Fortune helped settle her into a small third floor studio apartment in Greenwich Village, where she resided and worked for the rest of her life. Okubo said, “I find New York a place where one can get lost if one wishes because there is so much going on. New York is a good place for serious creative work.”3

In New York, Okubo showed Fortune magazine the 235 ink drawings of her camp experience. She remembers that people were surprised and excited by the drawings and then ashamed when they learned about the forced removal and incarceration. Some of the drawings were included in an article, “Issei, Nisei, Kibei” and published in the same April 1944 issue as her illustrations on Japan. Okubo began to organize her drawings into a book which eventually became Citizen 13660.

Hayashi said, “When Citizen 13660 was published in 1946, Tule Lake, one of America’s concentration camps, remained in operation. It’s amazing to think that this illustrated memoir, detailing the incarceration, came out when this wasn’t even recent history yet. It was a current event.”4

Nobuo Kitagaki, an artist before the war and an editor of Trek, remembered, “None of the University presses on the West Coast would handle the book at the time. It was the touchy subject matter and I guess they also thought that there would not be a large demand for the book.”5 It was the first book to show the concentration camps from the viewpoint of an incarceree. Although Citizen 13660 gave Okubo national attention, she continued to work as a commercial and freelance artist, illustrating publications such as Time, Life, New York Times, and numerous adult and childrens’ books. In 1951, she left the commercial art world to pursue her own art. She said, “I decided to go back into painting and dedicate myself to the highest ideals in art.”6

Okubo was single-minded in her view that “life and art are one and the same.”7 Over the decades her art evolved from being heavily influenced by Western art to her own individual style. She experimented with colors and subject matter. Her work became freer and often included subjects such as children and cats. She said, “In the end, I returned to the Primitives: Mayans and Orientals. By going the full route and by proving it myself, I went back.”8

In her later years, she continued to speak out about the injustices of the concentration camps. In 1981, she gave testimony to the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). During her testimony, she presented a copy of Citizen 13660 as evidence. Citizen 13660 was republished in 1983 and won an American Book Award a year later.

Okubo never married and said, “I never thought about marriage because I know this is a man’s world. When you marry, don’t kid yourself, you’re number two.”9 During the last few decades of her life, she was honored with various retrospective art exhibits including in Riverside, New York, Oakland, Boston, and Washington DC. Okubo passed away in New York City in 2001.

In her artist’s credo, a personal statement which she often xeroxed and mailed to others, she wrote, “My interest from the beginning has been a concern for the humanities. Having traveled and studied people and art in Europe, experienced the commercial world of New York, and lived (through) the Japanese Evacuation, I decided to follow the individual road of dedication in art instead of the popular arts of the times. By using all my technical ability and knowledge of art, I followed the difficult road of research and study….In art one is trying to express it in the simplest imaginative way, as in art of past civilizations, for beauty and truth are the only two things which live timeless and ageless.”10

Hayashi said, “I think Okubo’s legacy extends far beyond Citizen 13660. Ultimately, I think Okubo’s courage and intent on challenging norms, which characterized her entire life, are what define her legacy.”11

Notes:

1. Interview with Kristen Hayashi by Edna Horiuchi, October 17, 2021.

2. Citizen 13660, 1983, University of Washington Press, p. 123.

3. Kashu Mainichi, June 21, 1972, p. 41.

4. Interview, October 17, 2021.

5. Miné Okubo: An American experience, 1972 catalog of exhibition held at Oakland Museum, July 18–August 20, 1972, p. 29.

6. American experience, p. 42.

7. Amerasia Journal, a tribute to Miné Okubo, UCLA Asian American Studies Center, volume 30, number 2, 2004, p. 7.

8. American experience, p. 41.

9. American experience, p. 48.

10. Amerasia Journal, p. 7.

11. Interview, October 17, 2021.

© 2021 Edna Horiuchi