During the latter stages of World War II, Hollywood studios produced a number of war movies dealing with Japan, including Destination Tokyo (1943), starring Cary Grant; Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944), with Spencer Tracy; and James Cagney’s Blood on the Sun (1945). These films, generally dismissed as wartime propaganda, have been all but forgotten in cinema history. Yet one of them, the 1946 potboiler Tokyo Rose, deserves some attention for its part in Japanese American history.

The project that resulted in Tokyo Rose started life in summer 1945, as the Pacific War came to a close. The producing team of William Pine and William Thomas decided to make an exploitation film based on the character of “Tokyo Rose,” the legendary Japanese American woman who broadcast music and propaganda for Tokyo, and they pitched a story idea on the subject to Paramount Pictures. The project was accepted, and prolific B-picture filmmaker Lew Landers was signed to direct.

Perhaps for budget reasons, the producers did not select any “name” actors for the roles. Instead, they chose a unknown young actor, Byron Barr, for the male lead. After making an extended search for an actress to play the title role, in August 1945, the producers announced that Lotus Long had been selected. (See article on Lotus Long) Long, a mixed-race Nisei actress who had played Asian and Indigenous parts in movies during the prewar period, had not made a film since the outbreak of the Pacific War.

Tokyo Rose went into production in fall 1945, shortly after Japan’s final surrender, and soon garnered widespread media attention. There were calls for Tokyo Rose’s fate in the film to be harsher than what she would receive in real life. Studio publicists recorded that, even before the film’s release, Lotus Long was receiving a deluge of hate mail from families of servicemen and taunts from neighborhood children.

Tokyo Rose opened officially in February 1946. The film’s title notwithstanding, Tokyo Rose is a minor character. Although her voice is heard, Tokyo Rose doesn’t actually appear until a brief scene in the final reel. Instead, the plot centers on the story of a GI named Sherman who is interned in a prisoner-of-war camp near Tokyo.

Sherman has developed a hatred for “Tokyo Rose,” whose sweet-voiced radio propaganda broadcasts about unfaithful girlfriends back home have led his buddy Joe Bridger (played by future Hollywood director Blake Edwards) to despair and death in a Pacific jungle. Sherman and a group of prisoners are taken to Radio Tokyo on the orders of Colonel Suzuki of the propaganda service (portrayed by Chinese American actor Richard Loo, who made a career of playing evil Japanese during the war years). Suzuki tortures the prisoners and forces them to take part in a Japanese propaganda broadcast to the United States, to which he has invited a set of skeptical newspaper correspondents from neutral powers. A Japanese(-American?) radioman (played by Eddie Luke, Keye Luke’s younger brother) introduces Tokyo Rose as host of the show, but she remains unseen. Her disembodied voice is heard over the speaker as she interviews the GIs about their treatment.

The broadcast is interrupted by American planes which bomb the radio station. Sherman is wounded in the bombing but escapes in the confusion that follows. After taking the clothes and identity papers of a Swedish newspaper correspondent who has been killed, Sherman gets to the Swede’s home. There he meets Timothy O’Brien, an Irish newspaperman, who connects him with the Japanese underground.

Sherman makes his way to their secret cave headquarters, where he meets a team of agents who are working to get vital information out of Japan. These agents are portrayed by ethnic Chinese actors (including the remarkable 1930s proletarian novelist H.T. Tsiang). While the picture is not clear on their origins, most have Chinese names and appear to speak Chinese (when Sherman tries to leave, they shout “Chee Lai!” [stand up]).

The exception is Charley Otani (played by Chinese American actor Keye Luke), a Nisei from California. Otani refuses to tell how he got to Japan, but he reveals his American identity; when he hears music, he says, “Last night I was in America I went dancing at the [Los Angeles] Palladium.” Otani informs Sherman that an American submarine is coming to pick him up at anarranged rendezvous, but that he himself will stay on in Tokyo, because, he says, “There is more work to be done.”

Sherman is happy to leave Japan, but says that he wants to kill “Tokyo Rose” first. Otani agrees to help him. With Sherman again disguised as the Swedish journalist, the two sneak into the Radio Tokyo studios on the pretext of interviewing “Tokyo Rose.” They enter her studio while she is recording, kidnap her and force her to leave the station with them. They are chased by Suzuki and a unit of armed Japanese soldiers, but Sherman dispatches them all with a hand grenade.

They head to the appointed meeting place, where O’Brien informs them of the Atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Russia’s entry into the war against Japan. Then the agents say goodbye to Charley Otani and go out to meet the American submarine, presumably with “Tokyo Rose” as their prisoner. (According to Lotus Long, the script originally called for the character to die, but then the producers decided on a more ambiguous ending).

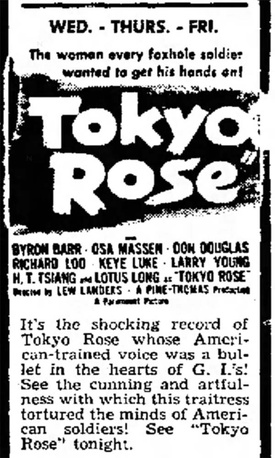

Tokyo Rose first opened in February 1946, then went into general release that spring. Advertising for the movie claimed, “It’s the shocking record of Tokyo Rose whose American-trained voice was a bullet on the hearts of G.I.s! See the cunning and artfulness with which this traitress tortured the minds of American soldiers!”

The movie was a financial success. However, it was greeted with mixed reviews by critics. The Hollywood Reporter called the film a “timely melodrama” that featured a lot of action, “none of it lost.” A reviewer in another journal agreed on the pacing but stated that it was rather “far-fetched” and regretted that it has not been released during the war. Donald Kirkley, writing in the Baltimore Sun, called the film “singularly inept,” explaining that it was “a fine specimen of the kind of infantile melodrama which reached the screen too often during the late conflict.”

Interestingly, the film’s (fictional) portrait of a Japanese American traitor did not attract criticism from the Pacific Citizen, which had denounced wartime propaganda films that depicted Japanese Americans as spies or saboteurs for Tokyo. Rather, focusing on Keye Luke’s character, editor Larry Tajiri lauded the film as a positive portrayal of Nisei secret agents working with the Japanese underground.

From a historical point of view, the film Tokyo Rose dramatizes the anti-Japanese climate of public opinion facing Japanese Americans as they left camp and sought a place for themselves in American society. One the one hand, it has certain progressive features, as compared to wartime hate films such as Little Tokyo, USA, or Let’s Get Tough. The film featured a heroic Nisei agent as well as a villain, and even the evil agent is at least played by a Japanese American actress—Lotus Long was the first Nisei performer to grace the Hollywood screen since early 1942.

All the same, there is something incongruous, and rather disingenuous, about a U.S. propaganda film centering on Japanese propaganda. The Japanese characters such as Colonel Suzuki are one-dimensionally evil. As for Tokyo Rose, she has no subjectivity—the audience is not given any information about her past, nor any explanation as to why she collaborates with Japan. Even as a fictional story, Tokyo Rose is unsatisfying in psychological terms.

Worse, the film was not merely a fiction, but a dangerous distortion of the truth.

By August 1945, the New York Times and other media outlets had reported that there were a number of women who performed English-language broadcasts on Japanese radio, and that none of the broadcasters involved actually called herself Tokyo Rose—it was a sobriquet invented by American GIs. Yet the film portrays an actual woman who calls herself and is called Tokyo Rose.

What is more, the film portrays Tokyo Rose as playing incessantly on GIs fears of unfaithful spouses, and asserts that her broadcasts were thereby directly responsible for the deaths of demoralized American soldiers. However, wartime studies of morale found that GIs considered Japanese propaganda broadcasts humorous, and did not take them seriously.

Just two years after the film’s release, Iva Toguri D’Aquino, a wartime broadcaster, was arrested and brought to the United States to stand trial as the “real” Tokyo Rose. Her 1949 treason trial, marked by government overreach, intimidation and perjured testimony, resulted in her conviction and imprisonment for 6 years in a federal penitentiary. Iva Toguri D’Aquino was pardoned by President Gerald Ford in 1977, but the pardon could not erase the injustice done her. This injustice had its roots in the black legend of Tokyo Rose, which the film Tokyo Rose did so much to propagate.

© 2021 Greg Robinson