The name of Léonard Foujita (AKA Tsuguharu Foujita) has lost much of its luster today. However, in his heyday in Paris in the 1920s, Foujita was not only the most celebrated Japanese artist in the world, but (along with Hollywood star Sessué Hayakawa) arguably the most famous living person of Japanese ancestry.

Born Tsuguharu Fujita in Japan in 1886, the son of a Japanese general, in 1913 he left Japan to seek his career as a painter in Paris (where he changed the spelling of his name to “Foujita” and most often went by his last name alone).

Although his debut exhibition encompassed a fascinating range of subjects that included paintings with gold leaf-like backgrounds that fused Christian and Japanese medieval iconographies, he soon settled into his most popular subject matter: portraits of ethereal Parisian nudes and languorous cats. Within the span of several years, he became one of the leading representatives of the circle of modernist painters collectively known as the “School of Paris.”

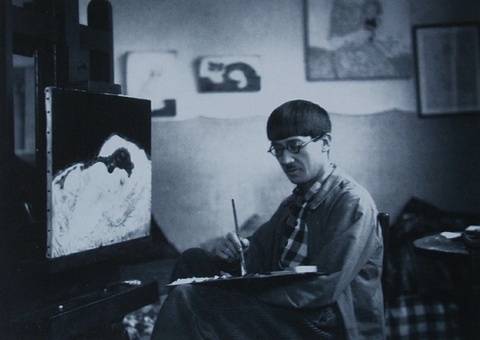

Foujita’s hallmark style fused elements of Western oil painting techniques with the fine lines and shading of Japanese woodblock prints and India ink brush painting (sumi-e), respectively. Foujita developed a uniquely opalescent white paint he called grand fond blanc, which, when overlaid by his perfectly executed black line drawings, imparted an effect that delighted bohemian and bourgeois audiences alike. Yet he also earned considerable notoriety for his flamboyant appearance, with his bowl haircut (a half-century before the Beatles), outsized eyeglasses, tiny moustache and outrageous costumes, many of which he designed for himself.

After sixteen years in Europe, Foujita began a period of international travel that commenced with his first trip back to Japan, from 1929 to 1931. His triumphant return to Japan, accompanied by his third wife Youki, occasioned many appreciative commentaries. Renowned novelist Kawabata Yasunari, for instance, made sure to mention Foujita in his own modernist literary masterpiece, The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa (1929-30). In the work, Kawabata recorded Foujita’s presence at the Casino Follies in Asakusa, observing: “Just back from Paris, the accomplished painter Foujita Tsuguharu has come to see the review, accompanied by his Parisienne wife Youki.”

After his stay in Japan, Foujita migrated to the United States for a series of gallery exhibitions. In November 1930, Foujita arrived in New York, where he had a show at the Reinhardt Galleries. He remained 10 weeks in New York. Among his many interactions with fellow artists during his stay, he made the acquaintance of the famed Japanese-born American modernist Yasuo Kuniyoshi. In January 1931 he moved on to Chicago for a show at the Arts Club.

Upon his return to Paris in March 1931, Foujita found Youki romantically entangled with his friend, surrealist poet Robert Desnos, and abandoned her to him (the two later married). Instead, Foujita resolved to tour Latin America. Ironically, it was at least in part Desnos’ enthusiastic visit to Cuba that seems to have sparked the idea for Foujita to tour Latin America. Foujita was also inspired to leave France after he received a hefty tax bill from French authorities for the large sums of money he had made during the 1920s. Foujita made the journey accompanied by a new romantic interest, Madeleine Lequeux, better known as Mady Dormans, a dancer at the Casino de Paris.

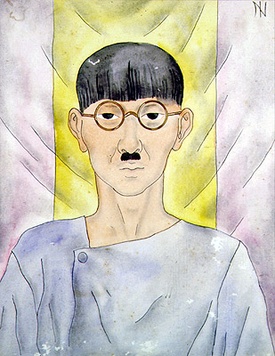

Foujita and Mady’s first stop was in Brazil. They arrived in Rio de Janeiro for a four-month long stay, conveniently timed to include the two major annual holidays of New Year’s Eve and Carnival. The Brazilian modernist community warmly received Foujita as a representative of the School of Paris. The painter Candido Portinari, whom Foujita had known in Paris, hosted him and introduced him to artists such as Emiliano di Cavalcanti and Ismael Nery, and the writer Manuel Bandeira. Their interactions not only extended to witty caricatures and expressions of mutual affection, but also an exchange of avant-gardist techniques, including the ultimate homage of imitating one another’s painting style. Nery’s watercolor of a nattily dressed Foujita and Mady receiving visitors to a gallery exhibition of his work stands out as one of the most elegant records of this brief, but intense encounter.

The Brazilian modernist poet, musicologist, and critic Mario de Andrade assessed Foujita’s work and praised him deeply in a review for the January 20, 1932 edition of the Díario Nacional, saying “Fujita [sic] represents one of those rare cases, aside from the intellectual arts of the word, of an artist of non-European race and essence, who has succeeded in becoming important from within the European conception of art” (Circulo, 49).

Andrade identified what he saw as the central theme of Foujita’s work: not the incapacity to faithfully reproduce the essence of European art, but to purposefully “betray” it. He argued that Foujita was indifferent to merging Japanese and European art, as others so often believed. Rather, he was an artist whose work was characterized by its “extreme silence, shall we say, plastically: a profound emptiness in his paintings and drawings. His sharp lines, the vast, blank surfaces, the true synthesis in its representation of theme, the relative coolness, or placidity of expression. All of these elements of his art, finally, leave me in a state of amazement.” (51).

Foujita took advantage of his time to paint. Although he continued to produce familiar works in portraiture, Foujita’s travels through South America marked a significant departure from his signature style. Not for the first time (or the last) would he court controversy, yet now he dedicated his work toward a wider palette of racial skin tones and social classes. Foujita was predictably drawn to the spectacle of pre-Lenten festivities in Carnival in Rio de Janeiro and À la porte au Carnival, and scenes from the red light district, such as his painting of four women in dishabille, seen from inside a bordello window, which was simply entitled Mangue, after the district itself.

Foujita also captured Rio’s vibrant street life of the city, in a marked departure from the modern themes that made his work so coveted by Francophile high society. In Deux gamins nègres (Two black youths), the young men wear looks of frustrated boredom and stare out beyond the picture plane. In People in Rio de Janeiro, five black female figures form a unified composition. Two barefoot little girls stand in the foreground next to a seated young mother with a melancholic expression on her face and hands fidgeting nervously. Two other young women stand ramrod straight with arms akimbo, one with her back turned and the other sternly facing left. Only the little girl at the center of the composition gazes directly at the painter, her head turned slightly and quizzically as he sketches them.

So began a new period of experimentation with ethnographic sketches, often done against a neutral beige background. His impeccable use of line and shading are still in force, but now his attention to intricate fabrics and textiles is directed to depicting indigenous folk garb, rather than the brocade curtains and bed linens of the Parisian boudoir. Foujita enthusiastically pursued this new approach along his travels through South America, and it continued well past his return to Japan in 1933. Some of these later works included such “exotic” subjects as a carnivalesque urban street musician in Chindon Performer and Serving Maid (1934), and a tattooed elderly Okinawan woman and her two grandchildren (1938) against a sumptuous tropical background.

Perhaps surprisingly, Foujita mostly seems to have flown under the radar of the Japanese Brazilian press during his time in Brazil. The overwhelming majority of the Japanese Brazilian community was concentrated in coffee plantations and agricultural colonies in the interior of São Paulo State. It was still a young community, about one hundred thousand strong, but growing at a frenetic clip in the early 1930s. More than sixty percent of that number had arrived in the previous five years alone.

It did not help that Foujita spent most of his time in Rio de Janeiro, and only in January belatedly arrived in São Paulo. Foujita was not as taken with the grey, commercial metropolis of São Paulo as the enchanting and considerably sunnier Rio de Janeiro. He complained in a letter to Portinari, “here it is cold and rains,” whereas he added, “we very much enjoyed our stay in Rio.” In fact, amid the turmoil of the Great Depression, the Manchurian Incident, which had occurred on September 18, 1931, and the larger political situation in both Japan and Brazil dominated the headlines of the ethnic Japanese press. The sole mention of Foujita’s visit in the five Japanese dailies appears in the supplementary Portuguese-language section of the Nippak Shinbun from January 1, 1932. He is lauded as “one of the idols of Montmartre and Broadway, admired in all the cultured cities of the world.”

Despite the lack of publicity attending his visit, Foujita did interact with community members. He met with the young Issei artists Tomoo Handa and Yoshiya Takaoka, who went on to co-found the Seibi Group of Nikkei modern artists in 1935, along with Walter Shigeto Tanaka, Kiyoji Tomioka, Yuji Tamaki, Hajime Higaki, Kichizaemon Takahashi, and the writers Kikuo Furuno and Yoshimi Kimura. Nor did Foujita’s influence end there. In 1935 novelist Orígenes Lessa penned a short story about an ill-fated young Issei artist who briefly becomes “the Brazilian Foujita, the national Foujita.” Due to the connections he made on his visit to São Paulo, Foujita would receive several promising Nisei artists such as Jorge Mori in Paris after the war.

After leaving Brazil, Foujita spent the next five months in Argentina, where he was met with almost unbelievable fanfare. According to his multiple accounts, sixty thousand visitors flocked to his exhibition, and ten thousand admirers stood in line to receive his autograph. Needless to say, he sold all his displayed works, and was directly commissioned for society portraits such as that of Carolita Cárcano de Martínez de Hoz.

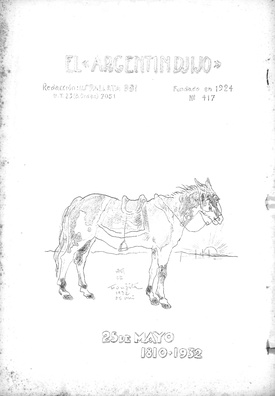

His interactions with the considerably smaller Japanese-language press in Buenos Aires likewise improved upon his experience in Brazil. He drew and signed an illustration of a horse, a popular gaúcho theme, for the May 1932 cover of the Buenos Aires-based Aruzenchin Jihō (or El Argentin Djijo, as it was then spelled in Spanish), and wrote a short article in his own hand congratulating Argentina in commemoration of its independence day. Unlike the better-established Japanese newspapers published in Brazil and the United States, the Aruzenchin Jihō was still mimeographed at this time.

After visiting several cities in Argentina, Foujita continued on his way through Bolivia and Peru. In Paris in Japan, art historian Emiko Yamanashi cites from Foujita’s travelogue Swimming Over Land (Chi o oyogu, 1942) in a section entitled “Observations of South America,”

During my long years of living overseas, I might even say among the unrepeatable experiences of my entire life, if someone were to ask me what lake I liked the best, I would say more than any other one I have ever seen I love Lake Titicaca on the border between Peru and Bolivia, in South America.

It is a fairly typical example of Foujita’s public statements, in which he was never prone to divulging his personal sentiments. Yet his works such as Llama and Four Women (1933), panned as disappointing by some of his Japanese and Latin American critics, reveals a desire to capture scenes in striking contrast to the spectacles of modern life his audience had come to expect.

Foujita and Mady arrived in Cuba on October 28, 1932, their only stopover in the Caribbean, before continuing onward to Mexico. Relatively little is recorded from the trip, although it remains open to interpretation whether this was due to the artist’s desire to keep Havana’s considerable charms to himself or other mitigating circumstances. According to biographer Phyllis Birnbaum, Foujita and Mady’s usual bohemian antics caused their fair share of trouble: “A Cuban journalist noted that ‘she created more confusion than a cross-eyed traffic cop.’” (Glory in a Line,168-169).

© 2021 Greg Robinson & Seth Jacobowitz