A number of Japanese Americans have distinguished themselves within the ranks of academia. From famed sociologist Tamotsu Shibutani to the members of the Manzanar guayule project, Japanese American scholars in a variety of fields saw their careers shaped by the wartime incarceration. One such individual, who rose to the top of the scientific world and contributed to the field of molecular biology, was Harvey Akio Itano.

Born in Sacramento, California on November 3, 1920, Harvey was the oldest of four children born to Masao and Sumako Itano. During his youth, Itano was active with the Young People’s Christian Conference, serving as treasurer, and became an Eagle Scout. Throughout his youth, Itano distinguished himself as a top student. His father, a University of California (UC) Berkeley graduate from the Class of 1917, encouraged his children to attend that university as well. During his four years at Berkeley, Itano excelled in his coursework and was even offered advance acceptance to UC Berkeley Medical school in January 1942 on the condition that he maintain his good grades.

In tribute to his feat of shattering all previous Nisei scholarship records at Berkeley, the Nichibei Shinbun dubbed Itano “the ‘brain boy.’” He was also active in the school chapter of the YMCA, where he was befriended by chapter president and Japanese American supporter Harry Kingman.

The coming of the Pacific War in December 1941 had a profound impact on Itano. First, his father was arrested by the FBI on February 16, 1942, on the grounds of possessing radio parts, and remained in FBI internment for over a year. Itano tried to join the U.S. Army in January 1942, but as a Nisei was classified as 4-C (“enemy alien”) and rejected. Even after he was later re-classified as 1-A (available for service) his request for review was denied.

Following Executive Order 9066, Itano had to prepare for confinement, and thus missed his final exams for his last year. Yet because of his high GPA, Itano was able to skip the exam and still graduate at the top of his class. Like his fellow Japanese American students, Itano was unable to attend graduation due to his incarceration. Although at UC Berkeley’s 1942 commencement ceremonies Itano was awarded a medal for scholastic achievement – a feat noted in the San Francisco Chronicle and Sacramento Bee - Berkeley President Robert Sproul stated that Itano was unable to receive it “because his country had called him elsewhere.”

Itano was sent with his family to the Sacramento Assembly Center in April 1942, and in June 1942 was confined at the Tule Lake concentration camp in Northern California. Itano's time at Tule Lake concentration camp, however, ended within a month. Before Itano’s incarceration, word of his academic success garnered the attention of Midwestern academic institutions.

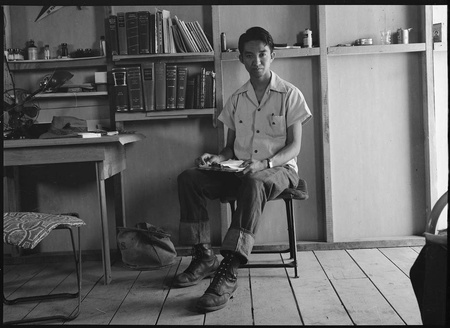

Immediately following his arrival at the Assembly Center in April 1942, Galen Fisher of the National Student Relocation Council contacted Itano with the intent of placing him at a school in the Midwest. Harry Kingman, who wrote numerous letters to government officials in support of Japanese Americans as a part of the West Coast Fair Play Committee, likewise encouraged Itano to apply to outside institutions. With letters of support from President Sproul and Vice President Monroe Deutsch, Itano successfully enrolled in St. Louis University Medical School. Although Itano spent most of his time in camp waiting for news of his acceptance, he was prominently photographed by noted photographer Dorothea Lange while in his barracks at Tule Lake.

In mid-July 1942, after special arrangements were made between the Dean of St. Louis University and the Army’s Wartime Civilian Control Administration, Itano became the first Japanese American student to leave the camps under the auspices of the new Japanese American Student Relocation Council. Itano was prominently mentioned in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in October 1942 as part of the first group of Nisei students to arrive in St. Louis, along with his brother Tsuyoshi.

While in St. Louis, Itano remained in touch with Rose Sakemi, a fellow Berkeley student who had become his girlfriend. Although Sakemi was sent to Poston, she left camp to finish her studies at the Milwaukee-Downer College and ultimately became a hospital dietician. Itano and Sakemi continued to court during the postwar years, and the couple married in 1949.

At St. Louis University, Itano met Edward A. Doisy, a Nobel Prize-winning biochemist noted for his discovery of Vitamin K. After Itano completed his medical studies in 1945, Doisy encouraged him to pursue biochemistry and suggested contacting Linus Pauling at California Institute of Techology, or Caltech, about pursuing a Ph.D. Pauling’s work on chemical bonds and the structure of molecules would win him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1954.

Itano’s interest in studying at Caltech may have been more than academic. A number of university faculty had been outstanding supporters of Japanese Americans during the war years. Robert Emerson worked as the project leader of Manzanar’s guayule project. Pauling himself had hired Japanese Americans returning from camp as domestics, despite harassment from white vigilantes in Pasadena. (The experience would help launch Pauling on an activist career that would culminate in his receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1962). Pauling eagerly agreed to take on Itano, and in 1946 Itano began what would become an eight-year program of study at Cal Tech.

It was during his graduate school years at Caltech, in collaboration with Pauling and S. Jonathan Singer, that the young Nisei made his most famous discovery, that of hemoglobin differences in sickle cell anemia. Using a process called electrophoresis, Itano detected differences in hemoglobin among red blood cells altered by sickle cell anemia. The discovery, which led to a formal publication in the acclaimed journal Science in November 1949, was recognized as the first solid proof of the existence of a “molecular disease.” Itano’s work generated strong interest in sickle-cell anemia and helped revolutionize views on molecular biology. In his nomination of Itano for the Theobald Smith Award, Linus Pauling stated:

“The discovery by Dr. Itano of the abnormal human hemoglobins has thrown much light on the problem of the nature of the hereditary hemolytic anemias, and has changed these diseases from the status of poorly understood and poorly characterized diseases into that of well understood and well characterized diseases.”

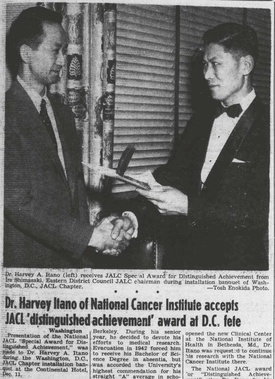

After receiving his Ph.D. in physics and chemistry from Caltech in 1950, Itano began working with the U.S. Public Health Service. In 1954, Itano and his wife Rose moved to Bethesda, Maryland, where Itano helped established a lab for the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Disease, a subsidiary of the National Institutes of Health. During his time at NIH, Itano continued his research on hemoglobin studies and protein sequencing. His work on sickle cell anemia garnered widespread acclaim among the African American community, whose members represented the population hardest hit by the disease.

In 1971, Itano was photographed by the Chicago Defender at the opening of an exhibit on sickle cell anemia at the University of Chicago. The following year, he received the Martin Luther King Jr. Award from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for his work on the disease. In 1979, Itano became the first Japanese American inducted into the National Academy of Sciences.

In 1970, Itano was recruited by the UC San Diego School (UCSD) of Medicine to be part of the initial faculty for the new school. Itano spent the remainder of his career at UCSD, retiring formally in 1988. In his later years, Itano regularly contributed to the Nisei Student Relocation Commemorative Fund, a scholarship founded by Nisei students to support Southeast Asian students, many the children of refugees. On September 11, 1992, Itano spoke before a special ceremony at UC Berkeley honoring Japanese American students like himself who had been unable to graduate in 1942 because of the incarceration.

He died on May 8, 2010 after a long struggle with Parkinson’s Disease. Itano’s passing was commemorated by numerous groups, with his obituary shared by UC San Diego, the National Academy of Sciences, and the Los Angeles Times.

Although Itano was one among many Japanese American scientists to advance our understanding of human health, his work on sickle cell anemia and career in public health underscored the relationship between science and social causes. Itano’s excellence stemmed not only from his ability to answer difficult questions in science, but also his desire to apply his research towards supporting others.

© 2021 Jonathan van Harmelen