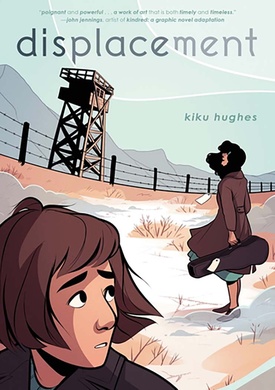

A time-travel graphic novel about intergenerational Japanese American camp history is a surprise. But even for readers versed in this history, Kiku Hughes’s Displacement is a powerful innovation in camp literature and Japanese American literature overall. Displacement brings together several current conversations in camp history: intergenerational trauma, the relevance of camp history for present-day history, tracing genealogy, the tradition of resistance to incarceration, and Japanese American queer history.

As a loosely autobiographical book, the main character “Kiku” is visiting San Francisco’s Japantown on a trip from Seattle when she’s pulled back into a scene from her grandmother’s past. The next day, she experiences another temporal displacement and goes through eviction with other Japanese Americans before coming back to the present. After returning to Seattle, she experiences several such “displacements” until she’s trapped in the past for almost a year. (Readers of Octavia Butler’s novel Kindred will recognize this form of time travel, rooted in traumatic history, and Hughes pays tribute to Butler in her notes at the end of the book.) Some of the physical and psychological scars from camp have an impact on the main character, and it’s not until she tells her mother about her travels that the reason for these temporal displacements becomes clear.

Hughes’s ingenious use of the time-travel device allows her to include several plot twists which refreshes the camp narrative for those who know it well. Along with Kiku, readers might know what happens next for those in camp, but readers do not know what will happen to the main character, why she’s time-traveling, and when she’ll finally travel back to the present. As befitting a book that travels through time, Hughes’s color palette uses a mix of sepia tones with muted colors which highlight a blend of the present and past. Her illustrations and pacing work beautifully together and are emotionally nuanced.

Importantly, Displacement is centered on the strength of Nisei and Sansei women. From the Nisei characters who mentor Kiku in camp (including a welcome cameo by Hughes’s literary ancestor, Miné Okubo) to the women who resist incarceration, to the Sansei activists who resist the model minority myth and form Tsuru for Solidarity, women are a powerful force in Hughes’s book.

Displacement is also a powerful queer intervention in camp literature, since it features a queer main character who is out as well as a requited love interest in the form of the Nisei character May (Masako) Ide. While May is not based on any one real-life Nisei woman, Hughes says, she did have the gay photographer Jiro Onuma in mind while writing the book. (Onuma makes a couple of cameo appearances.) Kiku experiences eviction and incarceration as a queer, part-Japanese, single young woman; she is outside of nuclear family formations which at times seem to deepen her sense of alienation and displacement, especially with the way that families were incarcerated as groups. However, she’s able to find a chosen family with other Nisei young adults, mentors, and neighbors while she’s trapped in the past, and she’s also able to deepen her sense of family through her mother and grandmother’s histories. (One historical point which might stretch readers’ credibility is the presence of queer couples at a camp dance. Hughes points to historical photos of women dancing together as “friends” during the same time period.)

The book also shows the important complexity of perspectives on cooperation and resistance. Whether it’s the election of a block manager in camp, the loyalty questionnaire responses, the choices to serve or not in the military, or the decisions to pass on the Japanese language to later generations, the book treats all of these situations with compassion and understanding. Choices are not demonized along a binary (good/bad) continuum.

As a younger Sansei (and the proud mom of a Yonsei queer teenager) who is co-writing a graphic novel about camp history and working on my own book about intergenerational trauma, I was heartened and inspired to read Hughes’s book. I look forward to reading what she writes next.

* This article was originally published on the International Examiner on November 3, 2020.

© 2020 Tamiko Nimura / International Examiner