The holidays are a special time of unity, with the end of each year bringing senses of joy and reflectiveness. For Japanese Americans experiencing incarceration during World War II, the New Year’s holiday elicited a number of responses that reflected both the importance of the traditional festivities and the anxieties of camp life.

For most Americans, the holiday season centers on Christmas; for Japanese Americans, New Year’s was (and, in many ways, still is) the center of the holiday season as an extension of the Japanese tradition of oshogatsu. In the prewar years, families celebrated the New Year by mochi making, or mochitsuki, along with preparing various osechi dishes such as fishcakes and pickled fruits. Japanese American dailies like the Rafu Shimpo and Nichibei Shinbun, printed special editions for the New Year that featured short stories and artwork. In their New Year’s 1941 issue, the JACL organ Pacific Citizen featured artwork by Chiura Obata and commentary on civil rights issues. Both the 1941 and 1942 New Year’s issues also featured loyalty pledges to the United States, with photos of Utah’s Secretary of State E.E. Monson and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt with JACL representatives.

Following Executive Order 9066, New Year’s festivities continued within camp, although with some modifications. The future psychologist James Sakoda later noted in his diary at Tule Lake that “since New Year’s is the big holiday for the Japanese people, they probably bought more things for that then they did for Christmas.” Although the Issei faced limited choices in camp as far as Japanese holiday foods to exchange with friends and family, camp stores stocked special gift items such as fruits and sweets during the holiday.

Throughout the week of December 31st, various camps boasted New Year’s activities. At Tule Lake, Sakoda noted the organization of a “jamboree” that included food vendors from the agricultural departments and games such as penny tosses. Towards the end of New Year’s Eve, a dance was held in either an auditorium or factory building in each camp, accompanied by a dance orchestra. At midnight, auld lang syne was played by a camp band to ring in the new year.

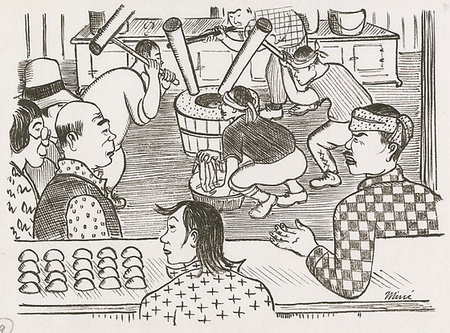

On New Year’s day 1943, celebrations continued with traditional Japanese oshogatsu ceremonies. Issei and Nisei joined in mochitsuki thanks to shipments of mochi rice from California, Texas, and Louisiana, or from wholesale sellers from Salt Lake City and New York City. At Poston concentration camp in Arizona, the Press Bulletin stated that mochi rice was brought in from Dos Palos, California—the site of the famed Koda farms that had once popularized Japanese rice growing in California. (Footage of mochi preparation at Heart Mountain concentration camp on New Year’s Day 1944 can be seen here. Footage of mochitsuki at Heart Mountain was also featured in Frank Abe’s 2000 documentary Conscience and the Constitution)

Special Japanese groceries were also obtainable thanks to outside importers from New York. Although alcohol was formally prohibited in camp, covert stills provided sake. Despite working on a limited budget, these ceremonies helped maintain a sense of community for the confined. Social worker Charles Kikuchi—later known for his elaborate diary of his camp experience—recalled how the Issei at Gila River pooled their money together to get mochi rice brought to camp, but couldn’t afford “those big red lobsters which are customary in Japanese homes.” Likewise, artisans constructed wreaths and other holiday decorations from local sagebrush found around the camp, while materials for pounding mochi were made from discarded wood.

Following the tradition from the prewar years, the various camp newspapers released a special New Year’s issue on January 1st. In addition to including a message from the camp director, the newspapers included both literary submissions and community reflections on camp life.

They were adorned with artwork designed by artists like Miné Okubo and Estelle Ishigo, and even occasionally included calendars for the year.

Unfortunately, New Year’s festivities were also halted on multiple occasions. At Tule Lake, the 1944 New Year’s celebration was cancelled because of the imposition of martial law, with military officials preventing mochi from being distributed among the confined.

Despite traditionally being a joyous time, for those in camp New Year’s reflections were emotionally tinged by the fact of their incarceration. At Poston, the 1942 New Year’s festival committee shared a frank but hopeful statement on the New Year that combined hopefulness for the future and despair over the realities of the incarceration:

“Year, 1942, an eventful, ruthless, war mad 365 days has finally parted our company. We are greeting the New Year, 1943, at Poston, Arizona, with high hopes that it will be a happy, victorious year…we all at Poston came to this desert jungle which was baked in unimaginable heat and intolerable dust under most unwelcome, undemocratic, and unAmerican circumstances.”

For others, the mood was even more abysmal. Charles Kikuchi lamented in his diary on December 31, 1942:

“I should feel gay and happy but I’m not. The next year doesn’t look so optimistic for all of us—all over the world. …Tonight, we are all supposed to be gay and force all of those hollow, dull pains out of consciousness. Quite a difference from last year when were free to do as we pleased.” For many like Kikuchi, the holiday underlined the inescapable reality of their confinement, and reminded many of how their lives were uprooted. In Manzanar, the 1943 New Year’s celebrations came just three weeks after the Manzanar “riot” in which two inmates were killed by guards. In the 1943 New Year’s edition of the Manzanar Free Press, the editorial section declared 1943 to be the “Year of Decision” for Japanese Americans, who faced the question of whether or not to maintain their American identity in the face of discrimination.

New Year’s 1945 brought with it a sense of hopefulness and relief, as a result of the news of the end of exclusion and a chance to return home. At Tule Lake, The Newell Star’s 1945 issue noted that the end of exclusion from the West Coast on January 2nd signaled an end to their confinement, with Director Best wishing the confined best wishes upon their journeys home. The issue was also tinged with sorrow, as it listed the events of the Army occupation that dominated the first half of 1944 and reminded readers of the murder of Shoichi James Okamoto by a guard. In the New Year’s 1945 issue of the Gila News-Courier, readers could find a special message from author Pearl S. Buck, expressing the hope that “never again must there be such a blot upon our democratic life.”

New Year’s in camp brought about a number of conflicting emotions. Camp inmates celebrated the holiday, carrying on or adapting many old traditions regardless of their situation. Still, for many it was impossible to forget the harsh realities of their lives in camp or the profound losses they had incurred due to their wrongful incarceration. New Year’s was celebrated throughout the U.S., but for Japanese Americans in camp, the holiday represented more than just the passage of time: it was a sign of their continuing perseverance and survival as a community.

© 2020 Jonathan van Harmelen