Every story has a point, a narrative, and a conclusion, but when I sat down to write this I couldn’t come up with any of those things. In part, I think it’s an occupational hazard of being mixed. Everyone’s understanding of self changes over time, but being mixed is often the lens through which I see this change and complexity in my own life. Blackness gives me access to a community, a history, and a world that is beautiful, joyful, powerful, and glorious. It also means I experience a great deal of pain and trauma that non-Black JA folx do not have to carry. It means I can experience painful alienation within the Black community. It means that many other less privileged folx in that community experience violence that I do not. Being a Buddhist JA also generates similar complex experiences, albeit with different stakes and different kinds of violence. So does being mixed when being mixed is different than being Japanese American and Black altogether. So does being female, and so does being queer. As a result, I’ve decided to share a few stories that I feel embody these ever-changing complexities.

I can’t remember a time when the Japanese American community was not present in my life. Though I was born in the Bay Area, I was three years old when my parents moved our family back to Los Angeles so that I could attend Nishi Center (Nishi Buddhist Temple’s pre-school). My Sansei mother was raised in LA, and returning also meant attending Senshin Buddhist Temple every Sunday, as well as a whole host of other JA activities like Sansei Baseball and several ill-fated attempts at JA basketball. In my formative years, I did not have to wonder whether my name, my religion, and my culture were valid and important. No place is perfect, but Nishi was pretty close.

This is not to say that my Japanese American Buddhist education in the early 2000’s is not a product of its time. I unquestioningly colored in the Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria n Nishi kindergarten as we learned about Columbus. I didn’t realize I was perpetuating Indigenous erasure and genocide — issues that had yet to be foregrounded in the Japanese American community in the ways that are so necessary for the dismantling of racism and settler colonialism. Even using land acknowledgements at the beginnings of meetings and events would go a long way (though not far enough) in recognizing that the land we have fought so hard to preserve against gentrification. Little Tokyo and other Japantowns, all of the spaces we consider “ours,” are only made possible because the Tongva people who were there before us were wiped from our history despite still existing today.

When I left Nishi for public elementary school, I was pretty miserable. Like many other children, I felt the discomfort of being “othered” throughout my childhood. Having a Japanese American name, lunch, and extracurricular activities were often more a source of embarrassment than they were of pride. It will always be extraordinarily difficult to explain what being raised in an intergenerational ethnic enclave community is like if you haven’t experienced it. How can I, at seven, articulate that even if the activities we do in the JA community aren’t actually Japanese in origin, they represent a powerful part of our history and help us understand, live, and heal today?

On top of that, I also feel some Black growing pains within the JA community itself. I became revolted with my body in the way that is only produced by gendered anti-Blackness. I was constantly thinking about slavery, King, and the Black scientists and inventors in my chapter books. I started picking up on the anti-Black comments that older community members made in my presence. My hair began to change and gained a more Black texture and curl pattern, and my mother and I were at a loss of how I could treat it properly. I’ve always been a lil bit of a butch queer, but that’s kind of hard to articulate at 9 when everyone else wants to wear pink tank tops from Justice and Claire’s. I once asked one of my former counselors at LABCC (Los Angeles Buddhist Coordinating Council) camp what they remembered about me during this time. They responded that my hair would get crazier every day of sleepaway camp. I think about this a lot, and how much that represented who I am, how I felt, and how the community saw me at this time.

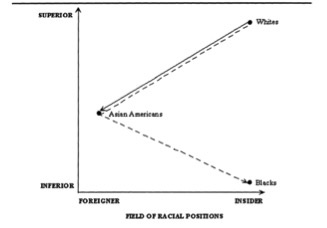

This changed drastically when I started high school. In college, I took a class called Afro-Asian Formations of Race with Prof. Daniel HoSang and, for the first time, was truly able to articulate my high school experience. In the class, we discussed how “Blackness” and “Asianness” as racial categories have been built together and in relation to each other. One of the early works we read was Claire Jean Kim’s paper on racial triangulation.1 While this is an older work and has therefore been, in my opinion, justly and thoughtfully critiqued over the years, the main gist is this:

- White people “valorize” Asian folx in relation to Black folx: Asian folx are considered smarter and more intelligent, more capable of professional and academic success, etc. This is the basis for the “model minority” myth.

- White people also present Asians as foreign and unassimilable to both white and Black folx on cultural and racial grounds. The idea that all Asians are presumed to be foreign-born or “fresh off the boat,” and the exotification of Asian goods, people, and culture; all of these things are part of it.

- It’s worth noting that the cultural “othering” of Black Americans is, to a certain extent, impossible, because of the erasure + homogenization of Black folx during slavery.

In high school, this triangulation was placed on my body, my mind, and my intellectual labor. When I received good grades or spots in high-level AP classes, it was “obviously” because I was Asian American. When I spoke out or dissented or felt anger or sadness, I was gaslit and tone-policed for being Black. I attended a typical Obama-era “post-racial” public high school, where “colorblind” teachers who "didn’t see race” policed Black and brown students of color for intellectually curious behaviors. Those same behaviors were lauded in white male students and in students who “acted” and “performed” whiteness.

I watched for years as this coding of Black students as loud, rude, and dumb destroyed investment in classes and instructors. This was compounded by the fact that “progressive” teachers used their “liberal” political stances to undermine and gaslight students who dared to be dissatisfied. I had extensive privilege that shielded me from the worst of this: my father is a college professor, I was academically capable of getting into Yale at a school where most were not, and I’m also Japanese American. However, I was just as patronized and tone policed as soon as I would challenge the presented curriculum because my challenges were inherently more threatening; they defied Asian stereotypes, confirmed Black stereotypes, and ultimately were policed. It was so bad that as I write this, I refuse to place my high school experiences in present tense for fear that they will again become real.

It was at that point that the Japanese American community became much more urgently essential to my identity and sanity. I was able to go from a hypercompetitive space that denied my identity, history, and lived trauma to programs like Kizuna or Jr. YBA (Youth Buddhist Association). These spaces and the wonderful people who made them possible allowed my thoughts, being, and personhood to be affirmed in ways that I so desperately needed. I was drowning; learning about community organizing and JA history kept me afloat.

Of course, all things must come to an end. Things became somewhat awkward when I decided to go to school at an Ivy League East Coast school. While friends and community members were thrilled (and as expressed, I literally would not have made it through high school or into college without them), it was sometimes tough to be different in a community that thrives on collectivity. It is tough to have a college experience that doesn’t revolve around NSU and Culture Night, good boba runs, and lots of Asian Americans. Additionally, my acceptance also changes my role in the community; I am growing up. Some people are not sure what to do with me; others decide they are going to be threatened. Both (often unknowingly or unconsciously) also enact anti-Black violence in that process. It’s impossible to know how much misogynoir interacts with people’s personal experiences and ideologies, but you know it when you feel it. In short, I went to college just a little bit heartbroken by leaving, but also because I didn’t feel I could stay.

Ultimately, college gave me exactly what I needed. Yale has a particularly strong Black community — one of the main reasons I chose the school — and for the first time I am able to really and truly be Black on my own terms. This includes big adjustments and personal reflection. My proximity to Blackness means that I am normally one of those most oppressed by colorism and anti-Black alienation in JA spaces. However, that isn’t the case when I’m in a room full of Black people. I laugh and I cry. I protest, a lot. I stay up late through fall, and then through winter. I miss 85 Degrees. I’m mad when I realize how cheap dorm supplies are at Daiso. I’m exhilarated by first loves and first snows. Sometimes life feels like the Gilmore Girls, and other times I am vehemently reminded that it is not. I find it tough to explain the pressure and violence of being Black at an elite, predominantly white institution, and it is something that I don’t think younger JA folx really hear, realize, or truly think about when I talk about college.

Now, I feel like I am starting to appreciate and understand the JA community for all it is and all it is not. If nothing else, I think that the JA community understands that everyone grows and changes. I was so worried that I’d be forever left out if I disappeared for a couple years, but I’ve found that isn’t the case at all. People come and go to find and lose themselves, but we can always come back. Over the past few months, in part because quarantine relocated me to Los Angeles, I’ve been able to return home, on my own terms, in so many ways. In particular, examining how JA Buddhism and other non-Western religions can be used to imagine alternative systems to policing, punishment, and labor exploitation has been an extraordinary and deeply comforting intersection upon which I’ve balanced. I don’t know what will happen in the future or how my relationship with the community will continue to change. I do know that, no matter what, it will always be there if we continue to nourish, invest in, and create space for ourselves.

Note:

1. Claire Jean Kim figure: Kim, Claire Jean. "The racial triangulation of Asian Americans." Politics & Society 27.1 (1999): 105-138.

*This article originally appeared in the “Diaspora” issue of Yo! Magazine, an online zine celebrating and exploring Japanese American stories, food, and culture.

© 2020 Mariko Rooks