1. Introduction

In the period between the Civil War and 1919, Chicago, Illinois very likely experienced more labor upheavals than any other city in the U.S., in the number of protests, and their breadth, intensity, and national importance.1 Chicago was a mecca in America’s radical labor movement, especially after the Haymarket Affair of 1886.

In contrast, socialism was imported to Japan, mainly from the United States. The 1894 Sino-Japanese war and the concurrent rapid industrialization of Japanese society helped foment acceptance of socialist politics, economic theories, and active labor movements. Well-known Japanese socialists came to Chicago beginning in the late 19th century and left their footsteps, where various new and radical ideas — from Christian socialism to anarchism — had been simmering for a few decades.

Sen Katayama, the first Japanese socialist educated in the U.S., constantly reported on Chicago in his publication, The Labor World, which helped spread knowledge in Japan on socialist activism there. For example, an article in the April 18, 1898 Chicago Tribune was translated into Japanese and appeared in the June 15, 1898 issue of The Labor World, claiming “Labor takes its stand; Chicago Federation to retaliate on nations that aid Spain. Adopts a resolution proposing a Boycott on the products of hostile countries.” Similarly, the articles “McKinley as Bricklayer,” from the September 9, 1899 issue of the Chicago Tribune, and “The Machinists’ strike,” from the March 3, 1900 issue, appeared in The Labor World on November 15, 1899 and May 15, 1900, respectively. As part of his role in connecting socialists in Japan and Chicago, Katayama became an exclusive agent for The International Socialist Review in Japan in 1904.2

Furthermore, Charles Karr, publisher of The International Socialist Review in Chicago, began amplifying the voices of Japanese socialists and supported their movements in November 1900. From all reports, it is realistic to assume that radical, socialist Chicago was an ideal, a place only dreamed of, for young Japanese socialists who wanted to witness the energy of the American working class.

Takeshi Takahashi boarded the SS Empress India with seventy dollars to his name on February 16, 1906, and arrived in Vancouver on March 1.3 He was a 19 year old student who had once attended Waseda Middle School in Tokyo.4 Waseda was known in those days as a school with a liberal atmosphere, a school where Isoo Abe, one of the founders of the first socialist party, established in Japan in May 1901, taught after returning to Japan from the U.S. in 1895. Takahashi arrived in Chicago in mid-March 1906, with a trunk filled with Japanese translations of books on socialism, including some by Karl Marx.5

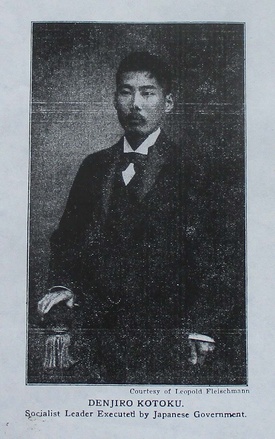

2. Denjiro Kotoku and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)

When Takahashi arrived in Chicago, Denjiro Kotoku was busily meeting with American socialists in the San Francisco Bay Area. Kotoku, a journalist who was severely persecuted by the Japanese government because he fought vigorously against the Russo-Japanese War, (which broke out in 1904,) had been sent to prison early in 1905 “as a Marxian socialist and returned as a radical anarchist.”6 In prison, Kotoku completely changed his outlook due to his communication with Albert Johnson, a seasoned San Francisco anarchist. Kotoku came to San Francisco in December 1905, after being released from prison because, in his words, “there is no other means to get freedom of speech and press than to quit the soil of the state of siege and go to a more civilized country.”7 He organized Japanese immigrant workers in the Bay Area and established the Socialist Revolutionary Party with about forty Japanese workers in Oakland, California.

Kotoku returned to Japan in the summer of 1906, but the Socialist Revolutionary Party continued to organize Japanese immigrants through its publication of Revolution, in Berkeley, beginning in December 1906. Interestingly, Kotoku’s stay in the U.S. coincided with the escalation of anti-Japanese sentiment and the Japanese exclusion movement in California. Japan’s victory in the war against Russia, the threat of “Yellow Peril” from Europe, and the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 vigorously escalated racist hysteria against the Japanese. As result, the San Francisco Board of Education passed a resolution to segregate Asian from Caucasian students in the classroom in 1906. Migration of Japanese laborers from Hawaii and Mexico was stopped in 1907 and the “Gentlemen’s Agreement” in 1908 halted Japanese labor migration to the U.S. Unfortunately, even American socialists participated in this anti-Japanese propaganda.

Samuel Gompers, of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), loathed Asian immigrants and called Sen Katayama a “perverse, ignorant and malicious mongrel...with a leprous mouth.”8 At the 1904 AFL convention, a resolution was passed that demanded the extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act to include immigrants from Japan. The California Socialist Party and the National Executive Committee of the American Socialist Party passed anti-Asian resolutions in 1906 and 1907 respectively, which resulted in a similar resolution passed by the Socialist Party of America at its national congress in 1910.9

On the other hand, in Chicago in 1909, a resolution calling for the amendment of the Chinese exclusion law to “include the Japanese, Corean, and ‘all other Asiatic races’” was vigorously debated at the National Women’s Trade Union League convention and the adoption of this amendment was urged by delegates of the San Francisco waitresses union, who attended the convention. But the resolution was “defeated overwhelmingly” by delegates from the University of Chicago Settlement, (a reform institution that provided poor immigrants with services to remedy poverty,) and some other delegates from New York, who “led the debate in favor of letting down the barriers to all races.”10 Was this due to the liberal soil of Chicago, where radical socialists had founded the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1905?

The IWW supported Issei activist Denjiro Kotoku and the Socialist Revolutionary Party that he helped form for Japanese immigrants, but were strongly in opposition to the Socialist Party of America. The IWW opposed anti-Asian resolutions adopted by the AFL and the Socialist Party of America and recruited Japanese members to join them instead.11 The IWW and the Socialist Revolutionary Party regularly exchanged publications12, and beginning in June 1907, the IWW even began distributing a leaflet entitled “Address to Wage Earners,” that was written in Japanese.13 IWW literature was sent “by all manner of routes” to Japan14 and Kotoku wrote a letter of thanks to the IWW in 1907, reporting that “I received the pamphlets, leaflets and reports of IWW which I highly appreciated.”15 In return, he sent his publication, Osaka Heimin Shimbun, to the IWW.16 In solidarity with the IWW, Japanese socialists and anarchists had grand expectations for the development of a similar social movement in Japan. Takahashi arrived in Chicago in the midst of this politically complex development of labor movements in the U.S.

Notes:

1. The Encyclopedia of Chicago, page 794.

2. Katayama, Sen, Beikoku Dayori, No. 9.

3. List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the US Immigration officer at Port of Arrival/U.S. Border Crossings –Canada To U.S. 1895-1960.

4. Shakai-shugi-sha Museifu-shugi-sha Jinbutsu Kenkyu Shiryo 1.

5. Maedako, Hiroichiro, Akai Basha, page 27.

6. Kotoku’s letter to Albert Johnson, dated August 10, 1905, Mother Earth, August 1911.

7. Kotoku’s letter to Albert Johnson, dated October 11, 1905, Mother Earth, August 1911.

8. American Federationist, May 1905.

9. Ichioka, Yuji, The Issei: The World of the First Generation Japanese Immigrant, 1885-1924, page 106.

10. Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1909.

11. Crump, John, A Critical History of Socialist thought in Japan from the end of the Russo-Japanese War to the Great Race Riots, page 236.

12. T. Takeuchi’s letter, March 30, 1907, Industrial Union Bulletin, April 13, 1907.

13. Industrial Union Bulletin, June 1907.

14. Wobblies of the World: page 37.

15. Industrial Union Bulletin, Dec 21, 1907.

16. Industrial Union Bulletin, April 4, 1908.

© 2020 Takako Day