Q: I only experienced Idaho through the Minidoka Pilgrimage and during that time, as you said it becomes like a “mini pop-up Japantown” and I don’t feel like I got a full grasp of what Idaho feels like. Can you describe what it feels like to you being in Idaho on a regular basis? And further elaborate what it felt like coming back from a Southern California college experience?

As part of a college paper I had to write, I had to look up my town and it was 96% white, which was just mind-blowing. It has grown a lot since then and it is starting to get more diverse, but I grew up kind of being somewhat tokenized. There were maybe a couple of Asians at my school.

Going to college, I think I have a very unique experience just because of the dynamics of Soka University. It is 50% international students and a large population of students are from Japan. I remember interacting with one friend, who is Japanese American and told me her grandfather was at Manzanar and that she didn’t identify with the Japanese students. I was able to better understand the differences between Japanese American and culturally Japanese identities.

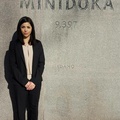

But I definitely got culture shock coming back to Idaho after college, especially during my first internship at Minidoka. I remember interning at this rural town where the population was maybe 800, and I looked up at this conference room and the staff was 12 middle-aged white people. And I think that was the first time I’d been a room where I stood out since before college. It was really striking.

But since then I feel like through work and the camp stuff, it has been a lot more about creating community. With the pilgrimages, the "pop-up Japan towns," and JACL, I’ve been getting involved and meeting the community that I didn’t know was here. Growing up outside of the community and feeling isolated, I've been able to reclaim and create community, and I feel fully part of things now.

Q: Did you ever wish that you grew up in a different area, location, and place? If so, why?

I think I always wanted to be around more of everything. I think a lot of people can't wait to get out of their hometowns, but growing up in the suburbs ora rural area, I felt my family was really mixed and well-traveled. I grew up going to Japan and Mexico.

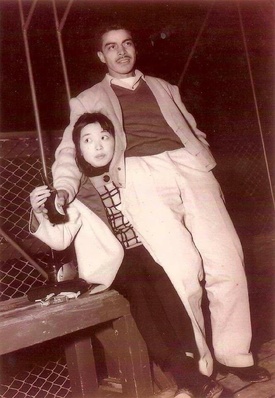

My grandpa was born to migrant laborers and they worked in the fields, and part of the reason why my grandparents were able to connect in Japan was because the farms that my grandpa’s family was working on in the 30’s and 40’s were owned by Japanese Americans in the Central Valley. He grew up with Nisei, interacting with them, joining them after work for ofuro, and they taught him children’s songs in Japanese, so when he went to Japan he had this knowledge. He always had this desire to see the world and travel the world. This was a kid in an immigrant family in Bakersfield, and he went to Europe and Japan in the military. When he was stationed in Germany he used his leave time to go to the opera and wineries. My grandma, too, grew up in a small fishing village and had this desire to do things differently. She went to fashion school in Tokyo.

I think having this background where people wanted to see more of the world, I always have grown up knowing my family was very open-minded and wanted to see what was out there, which is kind of a different mindset when you’re from a small town where people don’t always have it set as a priority to go see the world and see other ideas. I feel like that was the biggest benefit of growing up in a mixed family, where you already have this open-mindedness because you already have a clash of cultures, values, and ideas. I was already ready to go somewhere new and see the world. I think I am still like that but I am finding ways to feel like I am creating value in where I am now. Like feeling rooted. I came back for graduate school because of Minidoka and I am still trying to find my mission here.

Q: Going into your work at Minidoka, what is the experience like? What do you enjoy? What are you finding more about yourself and in creating community?

Obviously, pilgrimages are the best things ever. That is when Little Tokyo comes to us. We can go a long time without being around people so that is when burnout can set in, so whenever we have a chance to go on a pilgrimage, visit another site, or travel to Seattle, Portland, or Los Angeles and reconnect with people it is really energizing. When I’m able to have a phone call with a survivor or a colleague in the field, that is what fills my bucket to keep going.

I think the best part of the work is interacting with people that have such deep connections to the site that come and are able to enjoy the fruits of the labor. We get a lot of people sending us heartfelt letters, emails, and phone calls saying how much our work means to them. That is always the most important thing to me. I have a folder where I save letters. That is how we build our community too.

It can be hard to strike a balance in this kind of work. Obviously, we are passionate about it, care about it, and are connected to it, but when it is your day in and day out you start to see it as tasks to be done or projects to be managed. But when you see people interacting with it and telling you their story, their journey, what it means to them, or their family connection, those things are so precious. It is hard to strike that balance, especially when you’re dealing with this traumatic history day in and day out, so you have to separate it from yourself. So when you have these moments that humanize it, it just brings it back to the mission and to why we do it. I really feel like it is a privilege to be trusted to do this work.

Q: What are the challenges do you think you are to your location?

Most people think that Idaho is super remote, but I think we are the closest site to a major population center. There are still people, like me, who grow up here and have never learned about the incarceration. But now that the sites are being more publicized in the news, anytime we have a development we have people coming into town and telling us "my uncle helped build it" or people that grew up nearby saying "my parents told us not to talk about it and that it was not important enough to be preserved." It is a mixed bag here. People don’t learn about it.

But overall, I think there is a positive acceptance of this being a part of the local story too. A lot of our visitors are people who were either descendants or people who are on the road and will tell us “I grew up with a friend or in-law that has this as part of their history that wanted to learn more." It is a mixed bag, but I feel like those seeking out the site are already receptive to the story. I think the biggest challenge is to get the history more widely known in the state. I am in Boise and two hours from the site, and it is kind of surprising to strike a conversation with someone and find out they have a good amount of knowledge about it. It further reinforces my mission of broader education about the site and the history.

Q: Any last closing thoughts?

I think it is important for people to know that there is community here. Just because I didn’t know about it doesn’t mean that it wasn’t here. We’re only 30-40 minutes away from Ontario, Oregon, which during the war was the largest free JA community because it was just outside of the exclusion zone. Because there was such a large population of Japanese Americans there and they knew it was a safe space, many people resettled there and in nearby areas of Idaho that are more rural. There are also communities that were here before the war. The pre-war Japanese community in Idaho is something that I haven’t delved into much but they were here from the 1880s on the railroad and in agriculture all over the state. So a lot of the communities that we have are pre-war and, of course with resettlement, that mix of people who knew someone that could sponsor them so they left camp to go work on a farm where other JAs were. So there is a really robust traditional and multi-generational community here.

There are still folks who came here both pre-war and post-war. The community is getting smaller because we are losing a lot of our elders, and our local JACL is mostly a few families. But we are here and have been here for 100 years. We have four local JACL chapters across Idaho and on the Oregon border: Boise, Pocatello-Blackfoot, Idaho Falls, and Snake River.

Boise is really growing and it is becoming the city to move to, so I think we are having more and more people visit or move here that are looking for community. We also have a growing Shin Nikkei community here, since we have Micron, HP, and start-ups moving here. So there is more of a business community here, with families coming from Japan. We also have IJA (Idaho Japanese Association), and that is more of the Shin Nikkei community but our JACL works together with them. So there are different avenues with IJA, JACL, and Friends of Minidoka for people to get involved in community here.

Q: Tell us more about what you provided for us to download.

I wrote this zine in a creative writing class in 2012, at about the same time I was unpacking my identity for the first time in a lot of the ways I discussed with you. It's fun to look back and see how my feelings about my identity have shifted, and how much of my identity is rooted in my grandparents, who I am very fortunate to still have with me. I have been thinking a lot about how my identity will shift when that isn’t the case. One note - the “cosmic race” as imagined by José Vasconcelos was based on anti-Black and anti-Indigenous ideologies that a mixed/Mestizo race was a transcendent race of the future. There were echoes of this in magazine articles from the early 2000s talking about mixed people of the future that I also highlighted in the zine. Conversations around blood quantum and mixed generations are often heard in the Japanese American community as well. This raises the question of how we can strive to celebrate all people without continuing to erase historically marginalized groups.

To learn more about the Friends of Minidoka and Mia’s work, visit: www.minidoka.org

*This article originally appeared in the "Diaspora" issue of Yo! Magazine, an online zine celebrating and exploring Japanese American stories, food, and culture.

© 2020 Dina Furumoto