My name is Marissa, and I'm a Girl Scout from South San Jose, California. I love the smell of coffee, a good book, the sea at sunset, a couple of cats, and most of all, keeping history alive. I am currently working on my Gold Award, which is the highest award a Girl Scout can earn. It requires over 80 hours of work and leadership on a project that helps the community and has sustainability.

I am a fourth generation Japanese American. My maternal family came to America from Japan in 1923, while my paternal family immigrated from Japan to Peru. My dad came to America in 1988 as an engineer, learning English as his third language after Spanish and Japanese. But while he spoke Japanese, my mother didn’t. As a child, my parents only spoke English to me and my brother, and as a result, English was our only language. In school, mom and dad wanted me to focus on Spanish, while I wanted to learn Japanese. I was the only Asian I knew who didn’t speak the language of their ethnic country, and I felt as if a part of myself was being lost. As I got older, and the older folks in our San Jose Japantown began to pass away, I realized just how much of my culture and history was being lost as well.

In elementary school, I took odori (traditional Japanese dance) lessons with a well-known Sensei. She and my mom had danced together when they were young, and we were part of the very niche Bando community. But in fourth or fifth grade, Sensei passed away due to breast cancer. She was 51. It was then that I realized that our culture was disappearing. None of the other Bando members were willing to take on the role of Sensei, so with her death came the end of our entire Bando school. I would never be able to dance as well as my mom or my aunt, who had become legendary within the Bando community, because there were no more teachers.

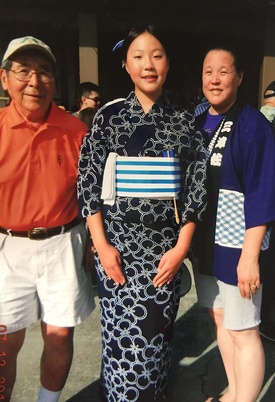

Yet another example of this loss of history, loss of culture, was with my maternal grandparents, who are also from San Jose.

My grandma’s house is full of interesting family heirlooms and weird knick-knacks, hiding in all sorts of nooks and crannies. When we visited as kids, she used to show us ancient tomes, detailing hundreds of years of Japanese history in beautiful kanji and woodblock prints (ukiyo-e), or intricately decorated stones that her mother made as a young girl. I loved hearing her stories, and as I watched the excitement light up her face, I realized that she had been trying to share our history for years, to uninterested family and friends. As age got to her, she eventually gave up and no longer tells us stories, but I still remember the wonder I felt each time I uncovered a new leaf in our family history.

My grandfather was the polar opposite. While grandma was quite talkative, he was very quiet and peaceful, always the one to buy us candy or take us to the movies. It is part of the Japanese culture to avoid any sort of bad memories or problems in an effort to fit in with the group, and not make anything about oneself. Because of this, he never spoke about his life, and it was hard to learn anything about him. It was only as he was getting older and sicker, that he decided to talk. Mom and I took notes as he spoke about the years he spent on the farm in Utah, after they fled California due to Executive Order 9066, which called for the roundup and relocation of any Japanese on the west coast. None of us had known any of this information, and it really made me realize how much of my own history I was missing. This, coupled with the joy and relief I saw on both of their faces as they told their stories and left parts of our family history behind, made me decide that I wanted to protect their stories and our history, protect this important part of America.

For my Gold Award, I have decided to educate the public on Japanese incarceration during WWII and how Angel Island fit into the narrative, in order to preserve this important part of American history, and to make sure something like this never happens again. I teamed up with the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation to locate, contact, and interview five living descendants of Japanese people who were interned at Angel Island during WWII.

First, I received a list of internees who were incarcerated at Angel Island during WWII, and then I used Ancestry.com to do a general search on the five names I randomly selected. Going off of the information I found in obituaries, I was able to find their living descendants, and I used Whitepages to find potential addresses. I then sent handwritten letters to each address explaining my project. Some of the families were harder to locate, so I posted the list around the Japantown community. I put it in the newsletter for our temple, the San Jose Buddhist Church Betsuin, and made weekly announcements in service. Some people came forward when they recognized names on the list (Angel Island held many internees from the Bay Area and Hawaii.) Finally, I interviewed them, either in person or via email, and published their stories on the Angel Island Immigrant Voices website and later on the Discover Nikkei website.

The genuine happiness of the descendants of these five people I had researched due to the preservation of their history and the interest it was garnering in others warmed my heart, and I knew I had to pursue this further. I am currently using this information to design four unique retractable banners, turning these stories and the history of Japanese incarceration into a professional traveling exhibit for Angel Island that will visit museums and historic sites all over the country for years to come.

But to truly make an impact, I had to take this to a new level. I led two 40-minute weekly webinars—one on Japanese incarceration and Angel Island and the other on incarceration in Hawai'i and the development of the 442nd Regiment—for youth and adults, highlighting how the problems of the past are still prevalent today, with the death of George Floyd and similar incidents. By explaining how to take action and eradicate social injustices, I make sure that everyone can learn a lesson from history that is applicable to their own lives. I refuse to let this generation continue with their eyes on the ground, impervious to the consequences of staying silent. I am proud to be a teen leader, keeping history alive in the minds of the youth and making a difference, one person at a time.

© 2020 Marissa Shoji