The idea of a war confrontation between the United States and Japan during the interwar period was a constant theme in the written press, in diplomatic circles and in public opinion in general. However, despite the increase in deepened tensions between those two countries in the early 1940s, the outbreak of the Pacific War—with the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941—came as a surprise to a vast majority of the planet's inhabitants. In Mexico, he hastened to break diplomatic relations with the Axis Powers, soon joining the concentration policies of the Japanese, German and Italian communities that lived throughout the national territory, adding the confiscation of their property and properties.

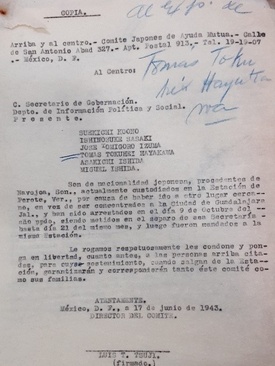

Sergio Hernández has documented in detail the reaction of the Japanese community to the federal government's demand for their displacement, either to Mexico City or Guadalajara 1 . In many ways, the administration of President Manuel Ávila Camacho was not prepared to implement these actions at the level of those carried out by the United States government, with the construction of 10 confinement centers that housed 120 thousand Japanese and their descendants 2 . In that sense, improvisation was a constant and, therefore, different media were produced in which the Japanese community was concentrated. The founding of the Mutual Aid Committee (CAM) was key to organizing it, and being the interlocutor with the authorities of the Directorate of Political and Social Research (DIPS) of the Ministry of the Interior.

However, the roots processes were differentiated. Some had the protection of state authorities who served as guarantees, others used their networks of political contacts to be protected and have some privileges such as residing in their own homes. However, the vast majority of the Japanese community had to move. The above not only implied spending large economic resources, particularly for those who were in distant places; They also had to face the fact of what to do with their properties and businesses. A large part sold their assets; others, however, “entrusted” neighbors or friends with their properties in which everything from dispossession to acts of honesty and solidarity were observed. On the other hand, for the Japanese married to Mexican women who had started a family, there was the certainty that some of them could continue to take care of the business or work to guarantee their livelihood, but it did not mean eliminating for the displaced the growing concerns for the well-being of your loved ones.

There is no doubt that the concentration order generated fear and a lot of uncertainty. Japan and its compatriots—inside and outside its territory—were considered enemies of the Allied Powers. Japanese migrants, who had considered Mexico their home and had assimilated into its culture and customs, were now considered a “threat” to the nation, some of whom had their naturalization revoked, as well as the cancellation of their process to obtain it.

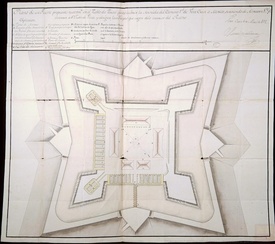

In this context, the story of five Japanese who did not comply with the concentration order is framed. All of them were detained by the federal authorities and, later, they were sent to the immigration station in the city of Perote, Veracruz, located in the San Carlos fortress and built in the last quarter of the 18th century, the same as during the 20th century. It was converted into a prison and during the Second World War it housed citizens belonging to the Axis Powers, mainly Germans and Italians, but also some Japanese.

Miguel Ishida López, son of “José” Asakishi Ishida and Felícita López, was 20 years old in 1942. In Navojoa, Sonora, he worked in the “Lucio” Surai soft drink shop. However, when the owner was concentrated, he was left without a job. In his search to earn an income, he left for Agua Caliente, Chihuahua, working with a salary of 3 pesos in a mine in that town. Miguel stated that after a month of being in that place, “Tomás” Tokuhei Hayakawa and later his father arrived along with “Isaac” Ishinosuke Sasaki and “José” Tomigoro Iduma.

On October 9, 1942, they were all arrested and so was Miguel, even though he was Mexican by birth. A pistol was found on him, without ammunition, and a 30/30 rifle with two useful expandable cartridges. In his interrogation before José Lelo de Larrera, head of the DIPS, he justified his possession by being the guardian of the mine and to protect himself against wild animals and some criminals.

His father “José” Asakishi Ishida entered the country on May 15, 1907 through the port of Salina Cruz, later he went to Monterrey to work in a brewery, and then moved to Chihuahua, Guaymas and finally to Navojoa, working as a farmer. While in that city, he received the order from the municipal president to go to Guadalajara. He says that, lacking money, he did not do it and went on foot with Sasaki and Iduma to the Agua Caliente mineral where his son Miguel was. Ishida was residing in that place for four months earning 2 pesos a day. In the interrogation before the DIPS, he pointed out that he recognized the mistake of not having complied with the ordinance to gather, because he was too poor to cover the expenses of his transfer.

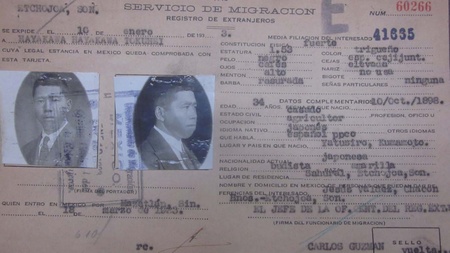

“Tomás” Tokuhei Hayakawa, originally from Kumamoto, entered the country in March 1923 through the port of Manzanillo, later he went to Navojoa, Sonora, to dedicate himself to agriculture and then moved to Etchojoa. When diplomatic ties between Mexico and Japan were suspended, on December 8, 1941, he grew vegetables on the Basconcobe ranch, municipality of Etchojoa, Sonora, belonging to the Ruiz Sánchez brothers, with financing from the National Bank of Mexico. Upon notification of the concentration, he left his business to Avelino Fernández to cover the outstanding accounts.

According to Hayakawa, he went to Agua Caliente, Chihuahua, to collect an alleged debt of 2 thousand pesos from Andrés Johnston. When he arrived at that place he found out that he had died, so he dedicated himself to working, earning a salary of 3 pesos a day. During the interrogation before the DIPS, he stated that his son Víctor Fumito Hayakawa was in Japan, but due to the start of the armed conflict he could no longer return to Mexico.

“Isaac” Ishinosuke Sasaki, 49, entered the country on March 19, 1923 through Nogales, from Los Angeles. Later he went to Navojoa, then started a business in Ciudad Obregón and married María Salcido, having six children with her. At the Basconcobe ranch he had rented four hectares for cultivation and, while there, he received orders from the municipal president of Etchojoa to concentrate. Sasaki pointed out that since he had no money, he went to the place where “Tomás” Tokuhei Hayakawa was, declaring before the DIPS that “he certainly loves his homeland, but he loves Mexico more, because he has lived here for quite some time and having gotten married.” with a Mexican woman…”

“José” Tomigoro Iduma, 56 years old, also worked on the Basconcobe ranch. He entered in 1906 through the port of Manzanillo, worked on the railroad, and later carried out agricultural activities. Iduma married Eloisa Ibarra, having seven children, and declared that the idea of going to Agua Caliente was with the objective of working and raising money for his move to Guadalajara. Likewise, he reiterated the fact that he has not spread ideas or propaganda in favor of the Axis nations and that he was dedicated to his work to provide financial support for his family.

On October 19, 1942, all of them were presented and admitted to the Perote immigration station under the responsibility of the special population inspector, Facundo Tello. Eight months later, on June 17, 1943, the CAM requested that the five detainees be released, a request that could be achieved with their endorsement. Some time later, most of them obtained, with the support of municipal and state authorities, permission from the Secretary of the Interior to return to Sonora and Coahuila, or embark on new paths by resuming their work activities and being able to be with their families.

The justification given by them for disobeying the concentration order was the lack of financial resources to pay for the transfer and their maintenance in Guadalajara. Perhaps it was the most important reason, but it can also be explained by the atmosphere of uncertainty and great anxiety regarding the change of a situation unprecedented for them since their arrival in Mexican lands. Surely, the quality of being enemies of the Mexican State was not easy to process for them and neither for their families.

Grades:

1. Sergio Hernández Galindo, “ The worst viruses: racism, lies and misinformation against Japanese immigration ”, Discover the Nikkei , May 1, 2020.

2. Sergio Hernández Galindo, “Japanese migration in Jalisco: From their entry into the concentration during the Second World War”, in Melba Falck (coordinator), Japanese Presence in Jalisco, University of Guadalajara, Japan Foundation, 2020.

© 2020 Carlos Uscanga