“Throughout a lifetime, one comes across by chance or by arrangement a certain energy that aligns with one’s own. Individual components are integrated to form a common energy to focus on how we see the world. This alignment when experienced, yields a state of well-being, comfort and assurance. The aesthetic and cultural practices in my work are related to my interest in Eastern philosophy, with its expression of serenity and spirituality. It recognizes the important aspect of time known as ‘the temporal moment’. There is a constant reference to appreciate the realm of ‘now’, not to focus on obsolete past or the unknown future. In Japanese art, the idea is to manifest the techniques but react intuitively and naturally, hence the result would be ‘Artless Art’...”

- From Akira Yoshikawa, Artist’s Statement

When Hamilton, Ontario artist and curator, Bryce Kanbara sent me a message that the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) had just acquired four of Akira Yoshikawa’s works for their permanent collection, I have to admit that I was unfamiliar with him.

Checking out his website, akirayoshikawa.com, I learned that he was born in Hiroshima, Japan, in 1949. His mother, Toshiko (nee Kodama), who was born in 1920 in Mission, BC, and was a victim of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb. She immigrated back to Canada in 1961 from the Eba district of Hiroshima with Akira who graduated from the Ontario College of Art in 1974 with a Special Commendation from the Department of Experimental Art. His work has been shown in exhibitions across Canada for many decades.

When asked to comment about Akira’s work, Bryce referenced a piece that he’d written in 1991 for the “Visions of Power: Contemporary Art by First Nations, Inuit and Japanese Canadians” exhibition at Harbourfront in Toronto: “Yoshikawa's is a perfect example of extended ethnic art, pulling familiarly towards the past and simultaneously stretching forward, and creating a mild and unprovoking tension. Our minds open and then empty in observing its harmonious refinement. In a way, Yoshikawa's work is the belated, graceful transition that we have been waiting for. Behind it are the silent and formal paintings of the Golden Niseis period (Nakamura, Kiyooka, Tanabe), and the traditions of Japanese art.”

Explaining how the AGO acquired Akira’s landmark work, Renée van der Avoird, Assistant Curator, Canadian Indigenous + Canadian Art, explained: “Over the course of 2019,” she recalls, “Akira welcomed me into his studio on three separate occasions. We discussed many aspects of his career in-depth, looking at work in storage as well as images in publications. Akira even installed certain works in his living room so that I could get a sense of what they'd look like in the gallery. Together, we pondered the question: which work would best represent his long and esteemed career? After careful consideration, we selected Spirit of Kendo (1988), a major work from Akira's early-mid career when he was exhibiting frequently across Canada. The work embodies his alluringly simple and concise visual vocabulary.

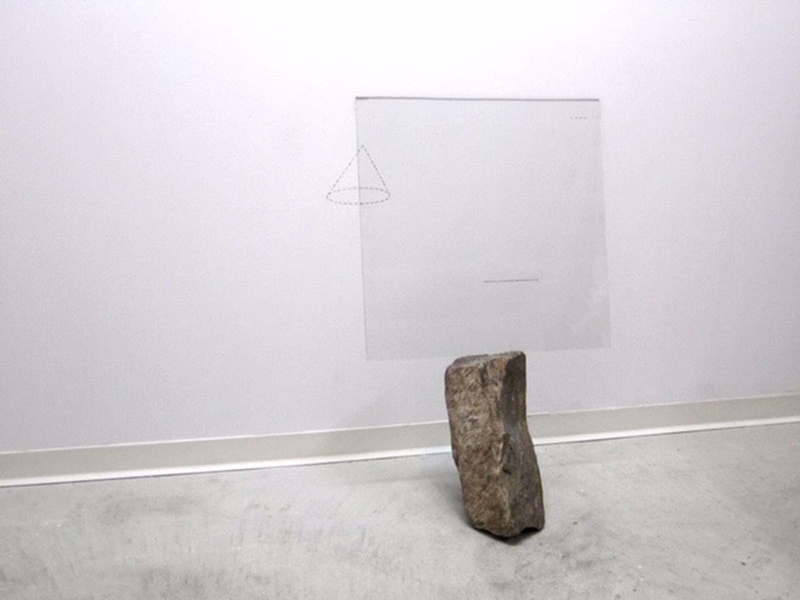

“Akira explained that Kendo is strenuous martial art in which ceremony, discipline, and precision are paramount. Spirit of Kendo reflects these values — a five-foot steel bar leans from the floor directly onto a large-scale graphite drawing pinned to the wall. The drawing is intense: three layers of heavily applied graphite epitomize the artist’s physical endurance. The diagonal line of the steel bar recalls the stroke of a bamboo sword, striking decisively into the space of an opponent. In this meditative yet energetic piece, Akira illustrates a moment of action through a series of poetic oppositions: heavy and light, solid and delicate, movement and stillness.”

The AGO purchased Spirit of Kendo directly from Akira. He offered to donate three untitled drawings to complement Spirit of Kendo. The drawings exemplify his interest in Minimalism, specifically the steel structures of well-known abstract artists like Richard Serra and David Rabinowitch. “In contrast to the precision of Spirit of Kendo,” she elaborates, “these drawings are purposefully smudged and stained, revealing traces of the artist’s hand. Geometric shapes cut from hot-rolled steel are mounted on to the drawings. Akira made these works after he stopped practicing kendo. As he distanced himself from the discipline of the martial art, he also moved away from restrictions within his practice and began to embrace elements of chance - hence the smudges. Together with Spirit of Kendo, the trio of drawings offers a strong representation of the height of the artist’s career.

Placing Yoshikawa’s work into the larger historical Canadian context, van der Avoird points out, “The acquisition of these four works addresses the AGO's mandate to develop a collection that reflects the cultural history of Toronto. Akira's work relates to works by other Toronto artists of the same generation, specifically the experimental early-1970s cohort of Ontario College of Art students: Colette Whiten, John McEwen, Barbara Astman and Ian Carr Harris, among others. Akira's work also resonates with the work of other Japanese Canadian artists in the Collection, notably Nobuo Kubota and Kazuo Nakamura, whose work similarly focuses on simple gestures, geometric forms, and inherent dualities (solid/empty, light/dark, organic/geometric, etc.).

Akira’s former OCA teacher and multidisciplinary artist Nobuo Kuboto adds, “That is great news about Akira. The sale of one of his works to the AGO has certain advantages: The AGO is a prestigious and important gallery. Other major galleries in Canada may investigate his work as a result. There is also the possibility that he may have more opportunities to show his work. He may also be noticed by other publications such as Canadian Art and major newspapers for critiques of his work.”

* * * * *

First, congratulations on the sale of your art to the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). When did you know that they were first interested in acquiring your work?

I had my initial meeting back in February 2019 with Georgiana Uhlyarik, the head curator of Canadian Art, along with her assistant curator, Renee van der Avoird. I was overwhelmed when they suggested that they were interested in acquiring my works. The acquisition process took three separate committees before the artworks were finally accepted into the collection.

Can you go into some detail and describe each of the four pieces that were acquired?

The four works they acquired are: Spirit of Kendo, 1988; Untitled #36, 1992; Untitled Composition, 1995; and Untitled #2. 1992. Let me just focus on one work “Spirit of Kendo”, a large-scale graphite drawing work completed in 1988: Size: 96”(h) x 50 x 13 (installed); Media: steel bar, graphite stick drawing on paper

During my early 30s, I was looking for a totally new physical activity to challenge myself. I had never done any martial arts up to that point. I heard from people that martial arts can help you to strengthen not just physically but also mentally. Through this process I had the romantic notion of attaining a higher level of consciousness. I was interested in cleansing my mind. I went to classes attentively a few times a week and loved every minute of it. One thing that was made clear to me was a common thread that runs through the Japanese way of life. It is the concept of “to endure”.

In kendo, one is told to practice one technique repeatedly, until you reach exhaustion. At that point it is finally embedded in you mentally and physically so that it has become a part of you. In the work “Spirit of Kendo” there are at least three layers of dense cross hatching drawn with graphite marks you see on the paper. This is my way to express the endured hardship one needs to go through in the Art of Kendo. The climax of the work is where a five foot long steel bar leans quietly but defiantly against the softness of the drawn paper.

The AGO is such an iconic institution in Canada. What does it mean for you to be included in its collection?

To have my works included in the Art Gallery of Ontario collection is such an honour. To think that there is a possibility of having my works installed in the same space with iconic pieces from their collection gives me a tremendous thrill.

As a Japanese Canadian, what does this mean for the JC art community?

I hope the Japanese Canadians would feel proud that the Japanese Canadian artworks were in a major art institution. I saw Kazuo Nakamura’s painting for the first time at the AGO while I was still in high school. I didn’t know who he was but I remember there was a sense of connection I felt because of our Japanese names. Never did it occur to me that we would be in a group exhibition such as the Japanese Canadian Centennial Exhibition organized by the National Gallery of Canada decades later.

There are works by other Japanese Canadian artists in the AGO collection such as Nobuo Kubota, Roy Kiyooka, Takao Tanabe, Louise Noguchi, Jon Sasaki (Instant Coffee), and Ron Terada.

Can you talk a bit about your family history?

My mother Toshiko Kodama was a Nisei, born in 1920 in Mission, BC on a family-owned strawberry farm. She departed for Hiroshima with her father just prior to the start of the Pacific war. My dad’s family is from Funairi in the city. My mother’s family had a farm in Miri, in the northern outskirts of the city.

While living in Hiroshima after the atomic bombing, she had to work to support the family; both my father, Yukiyoshi, and my sister, Hatsue, were very sick from the after-effects of the atomic bomb. She utilized her knowledge of English and Japanese as an interpreter, and worked at the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) a research hospital, managed by the Americans. While working there, she made a lot of American friends. They encouraged her to return to Canada after the deaths of my father and my sister.

Around the same time, she met a Swedish writer named Edita Morris. Morris wrote a bestseller book called “The Flowers of Hiroshima” which is a story based on my mother as a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Morris also suggested to her to return to Canada so that I would experience a better living condition. My mother decided to return to Canada in 1961. I was 12 years old at the time.

Why Toronto?

My mother’s intention was to go to New York City to meet up with her acquaintances from ABCC in Hiroshima. However, she realized that it was easier to enter Canada since she was still a Canadian citizen. She connected with her family friends from Mission, BC, particularly with the Nakashima family, who had moved to Toronto by that time.

This was the main reason Toronto was chosen as the destination which is also not too far from New York City, a place where she was still thinking of moving to. Once we arrived in Toronto, she got a job offer immediately at the Toronto General Hospital. She lived in Toronto until she passed away in 2006.

© 2020 Norm Ibuki