“For over 100 years, it (VJLS) has served Vancouver’s Japanese Canadian and local communities as a community-based educational, social, and cultural centre. This designation is a stepping stone towards having historic Japantown recognized as a Historic District by the federal government and I wish everybody continued success in this greater vision.”

— Santa J. Ono, President and Vice-Chancellor, University of British Columbia

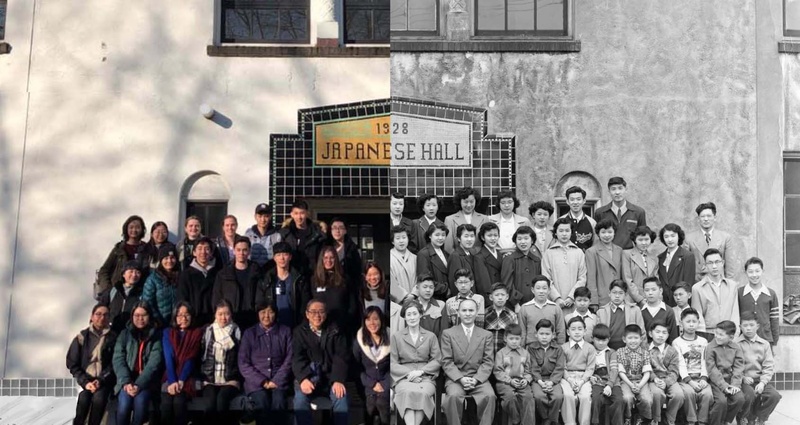

The Vancouver Japanese Language School (VJLS) and Japanese Hall have been designated a National Heritage Site. What a long, bumpy ride it has been….

This is an auspicious event for all Canadians, especially those of us of Japanese descent. Many of us, including yours truly, have family connections to the pre-WW2 VJLS located at 487 Alexander Street in the former Japantown/Powell Street area. My aunts Dorothy (Toshiko) and Kaye (Misae) went there.

I was fortunate to speak with resident historian, Laura Saimoto, Japanese Hall Community Relations Committee Chair. The school was founded in 1906, under the guidance of Japanese consul K. Morikawa, who formed a steering committee to guide the creation of the Vancouver Kyoritsu Nihongo Gakko (Vancouver Japanese Citizens). The original wooden structure stood at 439 Alexander Street. At first, the school followed the Japanese curriculum and taught math, history and science. In 1919, the curriculum changed teaching of the Japanese language only, leaving core subjects to be taught by the public school system. Its name was changed to "Vancouver Kyoritsu Nihongo Gakko" (Vancouver Japanese Language School). It was the first of 50 Japanese language schools that operated in BC before WW2. In 1928, the Japanese Hall, designed by Sharp and Thompson Architects, was added prompting the name change to the Vancouver Japanese Language School and Japanese Hall.

Just as my own students struggle with e-learning during these uncertain Covid-19 times, I feel a certain kinship with the teachers both before and after the lost internment years. Imagining the VJLS’s closure that affected 1010 students. While my own students struggle with a new learning mode and culture, I wonder if they could ever imagine being forced to leave their homes, being herded into Hasting Park animal stables, then exiled to internment camps in interior BC? As tough as these times certainly are, I take some strength from knowing how they persevered through those unimaginable times.

Afterwards, the 475 Alexander Street location was rented and occupied by the Canadian Armed Forces opened the Army and Navy department store until 1952. In 1947, half of the property was sold by the federal government to pay for the upkeep. In 1949, JCs were allowed to return to coastal BC. When the tenants vacated there in 1952, there was extensive damage to the heating system caused by a particularly cold 1950 winter. The other half of the VJLS property was reclaimed in 1953, the same year that the school reopened. In 2000, a five-storey wing was built adjoining the 1928 building.

Laura Saimoto, a second generation student of the school, was raised in the Kerrisdale area of Vancouver with her mom, Ritsu, a former student of the school, Dad Cy, and sister Deb.

* * * * *

First of all, congratulations on getting this very important designation. What does this practically mean for the school going forward?

Thank you. We are indeed humbled and truly grateful to become Vancouver’s new National Historic site. We join Metro Vancouver’s family of National Historic sites: Stanley Park, Lions Gate Bridge, and Steveston’s Gulf of Georgia Cannery. Going forward, the national designation brings much needed awareness and acknowledgement of Japanese Canadian history particularly in the Powell St. neighbourhood, the Internment and Dispossession.

Throughout 2020-21, we are aiming to do renovations to launch an Interpretive Centre. The centre will tell the story of our organization as a prism for sharing the Japanese Canadian story and bringing it to the present of the Downtown Eastside. The Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, once the vibrant market village of Historic Powell Street, was home to 8000 Japanese Canadian residents and over 400 businesses within about a three-block radius. It is not public knowledge in Vancouver, BC, let alone Canada nationally.

So our National Designation will provide us the base to launch Heritage Tourism and Education initiatives, such as historic walking tours, student field trips, and Pro-D training for in-service teachers to promote the education of history where it happened. Our operational model is the Tenement Museum in New York’s Lower Eastside, which was the early immigrant settlement area of New York City.

Can you go right back to the beginning? What is the story of how and why the school was built? Who were the founding members? How was money raised to purchase the land and build the first school? How much did it cost?

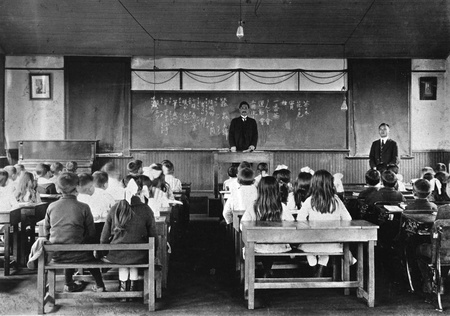

Founded in 1906 by early Japanese immigrants to Canada who built the original school house on 439 Alexander, it operated as a regular academic school in the Japanese language from 9 - 3 pm until 1919. In 1920, the school’s leadership, hoping to give a future to their children for a life in Canada, changed to a second language school. Children then attended after public school from 4 - 5:30 pm Monday to Friday.

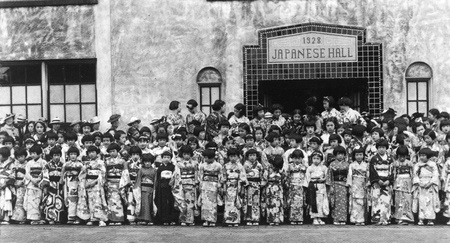

As the community continued to grow, the school continued to grow. Outgrowing the original building, the organization’s leadership fundraised $40,000 from the community across BC to build the 1928 Heritage Building. Recognizing that it could not be financially sustainable as a second language school, the leadership broadened its role in the community to a Japanese Hall (community centre), with education being one of its main pillars. As the educational, cultural, and community hub of the Japanese Canadian community in the Powell Street neighbourhood, when the war broke out in 1941, the student population was over 1000 students in a community of 8000. It was the largest of the 50 Japanese language schools operating in BC.

In modern terms, it is hard to imagine today going to Japanese School everyday after school. But before the war, there was no institutional childcare or after school programs. Both parents likely worked, so the Christian Church toddler kindergartens served in English served as both immersion English childcare and after school Japanese language programs served as immersion Japanese after school programs for working immigrant parents.

Who were the first principal and teachers? Any notables through the years? Now?

Principal Tsutae Sato was one of the main education leaders prior to World War II and also served as secretary on the board during the Internment. He was a great educator and one of the community leaders who helped to prevent the sale of the building during the war. In 1978, he received the Order of Canada for his half a century of service to educate the Japanese language and culture.

From senior alumni interviews, attending Japanese school everyday after public school was just a regular part of life. Most children attended Strathcona Elementary School, ran home for a snack at 3 pm, then went to Japanese school. My mother lived on Main & 22nd at the back of the family’s dry cleaning shop, so she took the streetcar (interurban) down to the school on her own in grade 1.

As part of our commitment to the education of our own history and Japanese Canadian history, we are planning the creation of an archives that will house many of our storied historic treasures, and eventually, expand into an accessible digital archive. A big part of this archive is our alumni database creation. We have a large number of student and membership lists which will enable alumni and their descendants to see when their relatives attended the school or served in a leadership role such as being a board director. So it’s coming!

Were classes pre-1942 mostly focussed on after school programs? Was it based on the Japanese curriculum? How many grades/levels were there? Did non-JC members enrol in classes too?

Prior to the war, the school was a second language school, so focussed on daily after school programs. What is interesting about the content of the teaching curriculum is that the educator’s leadership, led by Principal Sato, made a conscious decision when they switched to a second language school in 1920, to not educate children under the propaganda of the Imperial Empire of Japan. As the children were born in Canada and learned English at School, they had the intention to educate the Japanese language and culture so that if families went back to Japan, which was often the family intention, they would be able to get by. The first generation thought deeply about what and how they were teaching in classes. So for example, they stopped using solely Japanese Ministry of Education textbooks, starting to develop their own teaching materials, and in the late 1920s, starting using the western calendar year 1930 instead of the Emperor Reign year like Showa 5.

What kind of relationship did the school have with the greater community? How did that evolve over the decades too?

The Japanese Hall was the education, community and cultural hub of the pre-war Japanese Community in the Powell Street neighbourhood. Eight thousand Japanese Canadians lived in the area, with over 400 businesses along a three-block radius. The school was the largest of the 50 Japanese language schools operating in BC.

How did it typically deal with issues of racism and exclusion from the greater white community?

There was institutional racism and racial segregation, such as Japanese Canadians and naturalized British Subjects (like my grandfather) did not have the right to vote and were restricted to practicing their professional only within their ethnic community. The Powell Street neighbourhood was a fairly enclosed ethnic enclave, where you could buy anything Japanese.

So for kids, as Dr. Horii, one of our senior alumni told us, he did not experience racism until the Internment. At his elementary school, Strathcona Elementary, the oldest school in Vancouver, it was like a United Nations, with many immigrant children of various ethnic backgrounds. However, for adults, the restrictions on education, career opportunities, and business were limiting. The integration with the greater white community was happening at different levels. For example, the Asahi Baseball team led the way to melt racial barriers. For the school, an amazing discovery we found out while doing the research for our National Historic Site submission was that our architect, Sharp and Thompson was one of the most elite architectural firms in Vancouver in the 20th century. They also designed UBC Point Grey Campus, the Burrard Street Bridge and the very ‘white’ Vancouver Club. For this to cross the racial lines was very unique. Through personal and business relationships, it seems the bridge-building was happening.

How did the internment affect the school? How did it avoid being sold by the BCSC? Who took care of it until 1949? Was it repurposed? What was its status at that time (1942-49)? I’ve heard that some teachers/principals were targeted in the round up of JC leaders? Is this true?

When WWII broke out, the School was forced to close and the property appropriated by the federal government (BCSC). As it was a non-profit charity, owned by the community, it’s status was in legal limbo. All the board of directors were interned in different internment camps or passed away. The government, not knowing exactly how to deal with ‘associations’, as they called non-profit community organizations in those days, waited to sell-off association properties until 1946.

The government tried to force the board to sell, at a very undervalued price, however, the board refused, and through their lawyer, who was a downtown white firm, they used delay tactics and used the system to beat the system. From 1942-49, the Hall was leased to the Department of National Defence and then to the Army and Navy Department Store. With their lawyer’s support, they managed to get back into good standing with the Company of Registrars (in default due to no filing of annual reports and financial statements), and were able to reclaim the Hall in 1952. Thanks to the huge efforts of community volunteers who came back to Vancouver after the Internment, the Hall was cleaned up, repaired and reopened classes in 1953.

What was the state of the school after WW2?

The school had been heavily damaged by the tenants during the war. Community volunteers, themselves starting from scratch, got together to repair and clean-up the school for use again as a school. My father, who was a teenager at the time, helped to clean-up, repair and paint the now beautiful school bannisters.

When the ban on JCs returning to BC was lifted in 1949 what was the state of the JC community in the old Japantown Powell Street area? What was left of it? Did some return to the area?

The Powell Street neighbourhood was a social and economic vacuum after the war, what eventually became known as ‘skid-row’ and presently the Downtown Eastside. What was once a vibrant market village with children playing on the sidewalks, roller-skating to Stanley Park, baseball played in the Powell St. Grounds, it became a slum. Very few Japanese Canadians moved back to the neighbourhood.

© 2020 Norm Ibuki