At the US-led Pan-American Conference of Foreign Ministers held in Rio in January 1942, ten South American countries, excluding Argentina, resolved to sever economic relations with the Axis powers, and on the 29th of the same month, the Brazilian government also declared the severance of diplomatic relations with the Axis powers.

As part of its crackdown on "enemy nationals," the São Paulo State Security Bureau imposed restrictions on Japanese immigrants, such as "prohibiting the distribution of anything written in their own language," "prohibiting the use of their own language in public places," "prohibiting travel without a pass issued by the Security Bureau," and "prohibiting moving without prior notice to the Security Bureau."

Because of the times, although the "Japanese Pool" was completed, there were some defects in the paperwork, and it was banned soon after it opened. Tosaki Shinzo and Yamazaki Yoichi quickly went to the city of São Paulo to ask the Director of Sports of the State of São Paulo.

"They kindly showed us the procedure, and even though they were ordered to close temporarily during the war, they passed through with a letter of permission from Mr. Pasilia. It can be said that 'Director Pasilia created the world-famous Okamoto Tetsuo'" (Paulista Newspaper, September 18, 1952). Although he was an "enemy national," Okamoto was treated as an exception, and he continued swimming, even joining the local Yara Club to hone his skills.

Immediately after the end of the war, in March 1946, a "winner-loser conflict" broke out, plunging the Japanese community into unprecedented chaos.

After Japanese-language newspapers disappeared in 1941, Japanese immigrants had to rely solely on Imperial General Headquarters announcements on the shortwave radio station Tokyo Radio, and during the war they had been conditioned to believe that reports in Brazilian newspapers were a "conspiracy by the United States."

Therefore, immediately after the end of the war, Japanese people were divided into the "winners" who did not want to believe in Japan's unconditional surrender, and the "losers" who quickly accepted defeat, and faced the risk of more than 20 Japanese killing each other. The killings peaked between April and July 1946 and continued until the beginning of the following year, 1947.

The situation started to improve with the publication of Japanese language newspapers at the end of 1946, but the divisions continued for nearly ten years. In 1948, with the aftereffects of this conflict still lingering, Tetsuo, who was just 16 years old at the time, participated in the South American Championships held in Uruguay.

"The first swimming meet and the night in the capital" (Yukimura)

--My father, Sentaro, was delighted to compose such a poem.

In 1950, an event occurred that changed Tetsuo's life. A swimming team that was a pioneer of postwar exchange between Japan and Brazil arrived in Brazil on March 4th. The team included coach Masanori Yusa, captain Shuichi Murayama, Hironoshin Furuhashi (aka "Flying Fish of Fujimaya"), Shiro Hashizume, and Yoshihiro Hamaguchi.

In the prewar 1930s in Japan, competitive swimming was called "the country's specialty" and Japan dominated the world. For example, in 1932, the Japanese team won gold medals in five of the six men's events at the Los Angeles Olympics. One of the key athletes of that era was the team's coach, Masanori Yusa (two Olympic gold medals, one silver medal).

Okamoto, who had already become a member of the Brazilian national team, spent just over a month participating in friendly competitions with the Japanese delegation in cities with large Japanese populations, such as São Paulo, Marilia, and Londrina in Paraná state, and was deeply impressed by the world's fastest swimming.

With everyone standing, the national flag is raised and the national anthem resounds loudly in the night sky.

As a defeated nation, Japan was unable to participate in the London Olympics in 1948. However, as soon as Japan was allowed back into the International Swimming Federation in June 1949, six swimmers, including Furuhashi and Hashizume, were invited to participate in the U.S. Championships in Los Angeles in August, where they set new world records in the 400-meter freestyle, 800-meter freestyle, and 1500-meter freestyle.

As this was before the San Francisco Peace Treaty (September 8, 1951) was signed, there were no US dollars in Japan, and this great achievement was only made possible through donations from the executives of the Japan Swimming Federation and Japanese Americans living in the U.S. At the time, local newspapers praised the fish as the "Flying Fish of Fujiyama," which greatly encouraged the Japanese people.

The following year, in 1950, he was invited by the Brazilian Ministry of Sports to tour South America. Taking advantage of this opportunity, the All-Brazil Swimming Championships were held for four days from March 22nd at the Pacaembu Pool in São Paulo, where Furuhashi achieved great feats, including setting a new South American record in the 400m freestyle. At this time, by special arrangement, the Japanese flag was fluttering in public for the first time in eight years since the severance of diplomatic relations, providing great comfort and encouragement to the Japanese immigrants who had endured the difficult wartime period.

Yoshiaki Umesaki (93, Nara Prefecture), who actually went to the Pacaembu pool to watch the tournament, recalls, "Before the tournament, some people were quite cold and wondered what all the fuss was about, and I was the same. But as I watched the Japanese athletes perform, before I knew it, I was joining in the fun, and in the end, I was really moved."

He added, with deep emotion, "When the Hinomaru flag was raised, Kikuji Iwanami, who was standing next to him, was in tears." Iwanami gives the impression of being a calm intellectual, but on this particular occasion he seemed unable to contain his excitement.

"There were no winners or losers that time, everyone gathered at the pool. Because it was a swimming championships in Brazil, normally the majority of the spectators were Brazilian. However, at that championships half were Japanese. In that atmosphere, Furuhashi and the others won, beating the Brazilian athletes by more than ten meters. Seeing them win we all felt relieved, and when the Japanese flag was raised we all shed tears. Looking back on it now, it was a truly special day," he recalled.

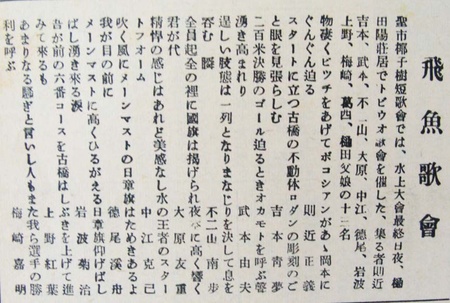

Umezaki was 27 years old at the time and was the youngest member of the tanka poetry society, Yashikoju. He went to see it with some of his seniors, and before the excitement had worn off, he stopped by a member's house to hold a "Flying Fish Poetry Gathering." The work was published in the April 1, 1950 edition of the Paulista Newspaper.

As Umezaki says, Iwanami Kikuji, a leader in the Brazilian tanka world, has published a poem filled with passionate emotion: "When I look up at the Hinomaru flag flying high from the mainmast, tears often well up in my eyes."

Other poems include, "Everyone stands, the national flag is raised, and the national anthem resounds high into the night sky" (Ohara Tomoshige) and "Furuhashi's motionless form as he stands at the starting line is like a Rodin sculpture, gazing at the viewer" (Yoshimoto Seimu). Most of the ten poems praise the bravery of the Japanese country and the Japanese athletes.

But there was one poet who wrote about Okamoto, with a different perspective. He wrote, "As the finish line of the 200m final approached, the voices calling for Okamoto rose up" (Takemoto Yoshio), vividly conveying the atmosphere.

Umezaki vividly remembers that time, saying, "It was a time when there were no famous athletes coming from Japan. There was a big fuss about flying fish, and no one was paying attention to Okamoto yet. Takemoto was a leading figure in the literary world of Colonia, and he took an interest in us second-generation athletes. He was someone who had high hopes for the younger generation, so perhaps he wrote the poem about Okamoto."

*This article is reprinted from the Nikkei Shimbun (August 11th and 12th , 2016 ).

© 2016 Masayuki Fukasawa, Nikkey Shimbun