My first surname (unpronounceable for some call center workers) has always raised a series of questions (some very strange and funny) that I have been able to answer and respond to with greater solvency as I grew and got to know myself. Are you from China? Why do you have that last name if you are Peruvian? Where are your parents from? Are you Japanese or Peruvian? Do you know anything about animes? Speak Japanese? How do you say “hello, Chinese”?

The truth is that I am a fourth generation Nikkei from Lima. However, this answer, apart from closing the round of questions, only fueled it. When I get to that point, I can't help but remember a testimony from the poet José Watanabe in which he told how, as a joke, his friends blamed him for the breakdowns of their Japanese appliances and congratulated him on Kurosawa's films.

Clearly, many of those who look at us (the Peruvian Nikkei) end up identifying us more with the country of the rising sun than with Peru. However, we are more involved with the Peruvian nationality than some believe. In fact, my ancestors and many other Japanese in Lima helped shape the current version of our capital.

THE RAPID PROGRESS OF THE JAPANESE

Since the end of the 19th century, Peru began to receive a large contingent of Japanese peasants who were escaping the poverty of their industrializing country. The men came with a work contract and the women came “called” by their husbands.

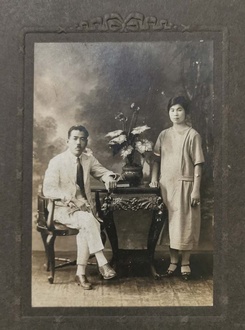

My great-grandfather Shiro Nakagawa arrived in Peru on the ship Anyo Maru in 1918 and years later he married great-grandmother Asano Sawa. My other great-grandfather, Kotaro Sakata, arrived in the country aboard the ship Duke of Fire in 1903 and settled in Mala. A few years later, my great-grandmother Saku Watanabe arrived and they started a family.

According to research by Dr. Mary Fukumoto, 1,174 migrants accompanied great-grandfather Kotaro on that boat. Certainly, the trip was complicated, but that would only be the beginning of a series of difficulties that they would face.

This group of immigrants faced xenophobia and racism from citizens who viewed their arrival and rapid progress with distrust. It didn't take long for the Japanese to begin to improve their economic status thanks to collaborative work and mutual support in the form of tanomoshi .

Many of those who stayed on the farms became yanaconas, like the Sakata Watanabe family: Kotaro, Saku, Elena (Fujie), Juan (Yukio), Fernando (Yukinori) and Yukito.

Those who settled in the capital opened businesses. This was the case of the Nakagawa Sawa, who even had a telephone in their premises when this device was a luxury for very wealthy people. My grandmother told with great pride the reason for this privileged acquisition: they washed the president's clothes and, for their comfort, he had ordered them to install a telephone.

The ventures were prospering and, soon, Japanese business guilds had been created. An emblematic case is that of the Hairdressers Association, founded in 1907. 17 years after this event, it is recorded that, of the 171 hairdressers in Lima, 130 belonged to a Japanese family. As the years went by, certain businesses became identified with the Japanese: wineries, bazaars, restaurants, carpentry shops.

The case of hair salons is a good example of this. Raúl Porras Barrenechea stated that “there is nothing more Lima than getting a haircut in a Japanese hair salon.”

The Japanese migrant community was so strengthened that it decided to participate in the celebrations for the centenary of the independence of Peru (1921) and the 400th anniversary of Lima (1935), so, for the first, it gave a monument to Manco Cápac (son of the Sun god, like the Japanese, the children of the rising sun) and, for the second, he gives the Nippon pool. Currently, this pool no longer exists and, in its place, we can find the North Stand of the National Stadium of Lima. On the contrary, the Inca sculpture can still be visited in the La Victoria district.

THE WAR THAT SEPARATED FAMILIES

Apparently, the most difficult years were over. However, very difficult times were still to come. It was the 1940s and World War II was raging thousands of miles from Peru. The Sakata Nakagawa family, like many other families of Japanese parents, fragmented: the Peruvian government, in alliance with the Allies, began to capture them to take them as prisoners of war to concentration camps in the United States. Some of their land was confiscated and they were forced to hide what little they had left for fear that everything would be taken.

I remember that it was said at home that my great-grandparents had buried a vase full of gold jewelry and other valuable objects in the farm, believing that, when everything was over and they returned to Peru, they would have enough to live on for a while until they recovered. As a child, I imagined the vase and also the treasure map while Dad recalled, as a meaningful paraphrase, his grandfather's words on the way to the ship that would transport him to Texas: “You don't have to cry. “Japan will win the war and give us double what they took from us.”

The truth is that, as we all know, Japan was defeated and, with that defeat, the hopes of recovering even a part of what was lost disappeared. During that time, those who remained in Peru endured harassment. The Japanese and their descendants were the enemies and any of their activities generated suspicion. Many schools closed, properties were confiscated and the exercise of various associations was frozen. The current Teresa González de Fanning school occupies the land that belonged to the first Japanese school in Lima: Lima Nikko, before the expropriation.

I remember with true rapture that Aunt Fujie, still in the concentration camp, through a letter whose back bore the phrase “enemy mail examined,” expressed to her brother how much she missed Lima. After the war, the Sakata prisoners (Kotaro, Saku, Fujie and Yukito) moved to their parents' hometown: Kumamoto. In another letter, already written from Japan, the only daughter of the Sakata Watanabe family told enthusiastically how she had found out that Peruvian children of Japanese parents were already being allowed to return to their country. However, despite the deep desire to return, no one did.

Aunt Fujie's letters showed the disappointment she experienced upon setting foot in Kumamoto, probably a very different place from the one she had heard her parents talk about. Maybe what happened to the obaachan Miyagi in the story “Okinawa exists” by Augusto Higa was happening to her. The old woman met every day with a friend at her house in downtown Lima to remember the blurry and distant childhood memories in Okinawa, Japan.

When she is hit by a car, the narrator tells the reader that, with her, Okinawa has died. And the land of the parents is an idealized place that no longer exists physically, but only in the imagination that family stories have built. The children of those migrants were born in Peru and identify with the climate, flavors and sounds of their city.

My grandfather Fernando (Yukinori) and his brother Juan (Yukio), who were not captured, were permanently separated from the rest of their family. Fernando settled in the Center of Lima, and formed a business and a new family. He opened a mechanical workshop in Jirón Leticia, behind the Nakagawa family laundry in Jirón Inambari, and married María Angélica (Shizuko) Nakagawa, a native of Lima.

My grandfather and my grandmother, like good Nisei , were very methodical and orderly people, a little sparing, but, above all, they were hardworking. Fortunately, their businesses prospered, as did many other Japanese families, which were spread throughout the city. I still remember my grandmother identifying families by their businesses: “Oh, your last name is Tokeshi! You are surely family of the watchmakers of Jirón Cañete.”

Each surname referred to a business and an address in Lima. Even today we can find some surviving businesses. I walk along Jirón de la Unión and see the Kurinaga jewelry store and the Arakawa bazaar; Also, the Tsukayama restaurant in the Central Market, and I can't help but wonder about the stories that are remembered behind those old counters.

For me, walking through Lima is reconstructing the history of Japanese immigration and, with it, my family history. Before, I used to walk along Colmena Avenue to the University Park and then go through Jirón Leticia or Jirón Inambari to imagine the family I never met. When I step onto Abancay Avenue and see the traffic congestion, I remember my father's stories of how, back in the fifties, he could play soccer on those same tracks that today are crossed with great difficulty.

Dad says that before not many cars passed by there and that that made it the favorite field to occupy when leaving school, a large school unit that housed children with Spanish, Italian, Quechua, Japanese and Chinese surnames, probably grandchildren of immigrants as well. that he.

CHILDREN OF A BOAT

The Japanese and their Peruvian descendants have collaborated with the transformation of Lima. Can a Lima menu be conceived without the olive octopus? Could we think of La Victoria without its Manco Cápac square? Can we imagine our city without a refreshing raspadilla under the summer sun? What is more Lima than homemade yapadel? What Lima native hasn't eaten some fried yuquitas with their rachi or udon soup at the Central Market? Can a peña criolla be called a peña that does not have the composition “Mal paso” or “Sacachispas” in its repertoire? Who doubts that Nikkei gastronomy is an important component of Peruvian cuisine?

I think that a sentence by the poet Watanabe fits like a glove here: “Beyond race, the Nisei (now Nikkei) are included in the contradictions of a Peruvian nationality that is still in formation.”

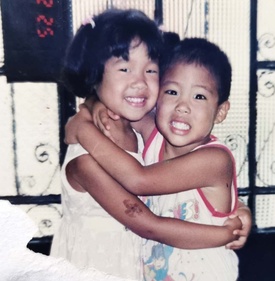

For me, Japan was in the food that my grandmother prepared, in the idioms that expressed everyday knowledge that she insisted on teaching me, in the Buddhist chants that she sang while leaving incense in the butsudan . However, I am aware that those flavors had Peruvian ingredients, that the phrases were translated into Spanish for me, and that our butsudan was full of little cards of local saints.

The descendants of those pioneers are Peruvians. Paraphrasing the urban narrator Augusto Higa: neither half Peruvian nor half Japanese, but Peruvians who do not deny their Japanese roots.

Finally, I see it this way: we Nikkei are the children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren of the courageous adventurers who dared to explore the unknown to provide a more dignified life for their loved ones. So, I think that we Nikkeinos descend from an Asian country. We Nikkei get off a ship.

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article published in Kaikan magazine No. 123, and adapted for Discover Nikkei. (This text was published for the first time on the Ríohablador portal ( https://riohablador.com ), a group made up of graduates from the Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences of the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima).

© 2020 Yuri Sakata Gonzáles/Asociación Peruano Japonesa