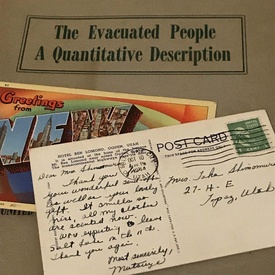

For scholars of Japanese American history, telling the story of incarceration is important yet difficult. Doing justice to the complicated narrative of camp life and the experiences at ten unique camps across the deserts and swamps of the U.S. is not easy. As a historian, I find it is important to look beyond government records and interviews when I write about the history of the incarceration. One way I do so is by examining objects of incarceration. In a previous article, I discussed the ways in which personal items such as postcards help tell broader stories of removal and resettlement and personalize the story of incarceration.

At the National Museum of American History and the Japanese American National Museum (JANM), artifacts such as letters, suitcases, or segments of barbed wire help to visualize narratives of the imprisonment experience. Although items such as a bill of sale or a death certificate seem typical, their association with the incarceration emphasize ways victims were stripped of their property, their liberty, or even their life as a result. While museums serve an important role as a repository for objects (hence the Smithsonian’s moniker “the Nations Attic”), exhibits allow museums such as JANM to transcend from its mission as a space for housing objects into a community center for preserving memories, and is why they are cherished by visitors.

In reality, not all artifacts related to the camp experience wind up in museums. Because the majority of artifacts are donations to museums, the place of origin of what one sees behind the glass is, sometimes, someone’s attic or garage. When they don’t find their way to museums, however, what happens to artifacts is a number of things: they remain with the family, they are tragically discarded, or they are sold off.

Over time, a market has emerged for camp artifacts. Like other items from World War II, camp artifacts such as letters, camp documents, or artwork have been bought and sold for a number of years. While there are multiple explanations for this, one central reason is the passage of the camp generation that saved their personal belongings. Now, as families inherit family heirlooms from camp, the question of ‘what to do’ with them is becoming more prevalent.

Yet activists have called into question the ethics of selling camp artifacts such as artwork created in the camps. The most famous example of this is the 2015 Rago Auction of camp artwork previously belonging to the Allen Eaton collection. Following the announcement of the auction, dozens of scholars and activists organized behind the groups “Japanese American History Not for Sale” and the Heart Mountain Foundation to successfully help call for Rago to suspend the auction and sell the artwork directly to the Japanese American National Museum.

While there is nothing illegal about selling personal possessions, selling objects of incarceration pose a number of ethical questions that are worth discussing. On the one hand, it is the right of the owner to decide what to do with such objects. At the same time, part of the mission of raising awareness of the incarceration experience is through education, and artifacts are one of the best ways to connect with the public on both the hardships and legacies of the camps.

Whether one choses to donate, sell, or keep such objects, the best thing for families to do is to learn more about what they have. Connecting objects through family stories not only serve as a personal history lesson, they add a value that cannot be appraised monetarily and are what make history enjoyable and enriching. If you choose not to keep them, check with a local museum, JANM, Densho, or the National Museum of American History. In addition to preserving artifacts, museums and advocacy groups like Densho photograph and scan artifacts so they can be shared online, providing educators and the public with a ready means for learning about the incarceration experience. And for those worried about permanently donating items to museums, Densho returns items to the families after they have been scanned. Whatever the choice, the lesson we can take away is the value of history is something that cannot be appraised monetarily.

*This article was originally published on NikkeiWest on April 10, 2020.

© 2020 Jonathan van Harmelen/NikkeiWest