…for me and my family anyway. Back in 1920, my father first came to Canada from a small village called Kiyama, Fukui-ken, Japan. His father, my grandfather, had brought him and his chonan, his first son, my uncle, to work. Poverty plagued Japan at the time, according to Toyo Takata, our first Nisei historian, and jobs were hard to come by. So many came to North America temporarily to find work.

It was the time of the “Gentleman’s Agreement,” so they couldn’t easily immigrate with wife and children in tow. Not until the late ‘20s. In any case, my grandfather owned a rice farm in Kiyama and didn’t want to give it up.

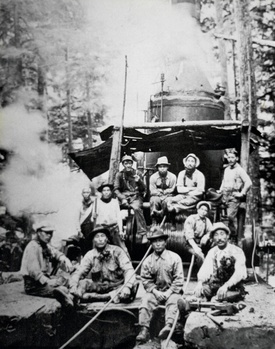

Hidematsu, my grandfather, had made several trips to Canada in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, so he was very familiar with the labour situation in British Columbia. As far as I know, he primarily worked in the lumber industry, but I understand he took jobs in mining (mostly on Vancouver Island, probably in the Cumberland area) and in railroad work.

His first son, Shigetaro, would inherit the farm, but, I’m guessing, Hidematsu wanted his sons to have work experiences. Moreover, he knew the best chance for his second son to have a good life was in Canada. Matsujiro (my father) after all stood to inherit nothing.

So it was that Hidematsu brought his two sons to Canada. He set up Matsujiro with a job and a place to stay. Must have been quite a shock to learn that his father and brother went back to Japan, forcing Matsujiro at fourteen-years-old to fend for himself.

I don’t really know how he felt, but there is some indication in a letter home while he was aboard the ship to Canada.

Hello to the household,

…My mother, my older sister and so on, not a day goes by that I fail to think of them. Tell them not to worry about me…

From the ship, Watada April 15, 1920.

The remarkable thing about the letter was the fact that he hadn’t put it in the mail on board or in Vancouver. He simply rolled it into a bottle and threw it into the Pacific Ocean. It eventually floated up the coast and followed the Aleutian Archipelago until an Aleut plucked it out of the water. He in turn gave it to a US Navy Captain stationed nearby. The officer recognized it as being written in Japanese and so naturally thought it was a bit of espionage. He sent it on to Washington DC, where translators found nothing insidious about it. They sent it on to Japan. A decade later, my dad retrieved the letter during a visit, which he brought back to Canada. It and the story are part of the family lore.

My favourite story about my dad concerns his first venture into gaijin territory. During the first weeks of his stay, he explored Gastown, which neighboured Powell Street (where the Japanese lived). The oldest part of Vancouver, it was rough and tumble at the time, consisting of bars and rundown hotels for the white workers who came to town. My father, being a curious boy, wandered into a café, probably because he smelled the food cooking. He sat at the counter and waited.

Eventually, the short-order cook approached him and allegedly said, “What’ll it be, Mac?” My father didn’t know English and so stared at the gaijin until the man opened a menu in front of him.

Dad must’ve understood because he pointed to an item in it. The cook nodded and proceeded to prepare food. In a few moments, the cook placed a plate of sausage and eggs before the young Japanese boy.

Matsujiro had never seen food like that before, though he said the aroma was heavenly. He proceeded to devour his breakfast with particular attention to the sausages. He found them to be a taste sensation.

He returned to the same café and ordered the same thing everyday for a couple of weeks. He confessed to me that he felt he got lucky and didn’t want to risk ordering something else, in case, he hated it. In due course, he grew tired of sausages and so stopped going. In fact, he never had sausages for the rest of his life.

There are many more tales to tell but I have limited space.

Let me conclude by acknowledging that other families have been here for more than 100 years. Japanese Canadians have been here since 1877 (again according to Toyo Takata), but 2020 is quite a milestone for my family. It gives us a sense of belonging. I am indebted to my father for having endured so much: the loneliness and insecurity of his adolescence, abandoned as he was in an alien land; the internment and then exile to another alien part of the country; and the hard life he led as a blue-collar labourer in Toronto. I suspect there were moments of great joy and love, but in general, he led a life of struggle and sacrifice so that his family could enjoy a future of opportunity and promise.

Matsujiro Watada died in 1987, and if I could say something to him now, it would be, “Dad, you did all right. All my love to you.”

© 2020 Terry Watada