One of most divisive chapters of the Japanese American incarceration is the story of Tule Lake. While established as a traditional War Relocation Authority (WRA) camp, it was declared a “segregation center” by the WRA to meet Congressional demands issue loyalty oaths and begin military recruitment within camp. Of the 120,000 Japanese Nationals, and Japanese Americans that were incarcerated starting in 1942, about 10,000 were labeled as “No, No” Boys: troublemakers who refused to answer two questions of the infamous ‘loyalty oath’ related to loyalty and military service, and were labelled anti-American. Of the approximately the 10,000 at Tule Lake, less than 5,000 were stripped of their American citizenship and repatriated after the war. Although some had lived previously in Japan, for many it was their first time to leave the United States.

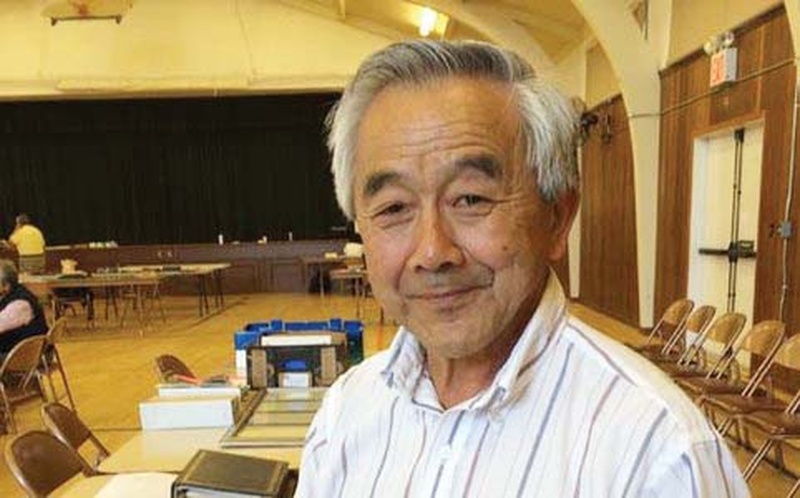

Thanks to the activism of Barbara Takei and Konrad Aderer’s film Resistance at Tule Lake, the story has become recognized. I had the chance to interview teacher and activist Henry Kaku about his family’s experience in Tule Lake and repatriation. Born in 1948 in Japan, his family repatriated to Japan after their incarceration in Poston and Tule Lake Camps.

* * * * *

JVH: Were did your parents live before the war? What was their work?

HK: My father, Keige Kaku, was born 1915 near Fresno, and his family moved to Brawley, California, near the Mexican border around 1930. There his family worked as farmers. My mother, Sumiko Tajii, grew up in Calexico, California, near Brawley, and was born in 1920. When WWII began, they were not married, but were sent to Santa Anita Race tracks, and then to Poston Incarceration Center in Arizona, the largest of the camps. There they met and married while incarcerated in Poston. Shortly after in 1943 my sister was born in Poston.

Before the war, my father joined the peacetime army in early 1941, and was sent to Georgia in the Army Corp of Engineer for training. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, the Commanding Officer kicked my father out of the army because of his Japanese ancestry and was sent home, something that would later influence his decision to repatriate.

JVH: Did they immediately go to Tule Lake? How long did they stay at Tule Lake?

HK: When the military issued the loyalty questionnaire to all persons over 17 years of age in it were two infamous questions that they asked to “weed” our those who were considered dissident and trouble makers: No. 27, where they asked if you would serve in the military; and No. 28, where they asked if they would swear allegiance to US and denounce any loyalty to Japan and to the Emperor.

My father refused to answer No. 27 saying “I was in your Army and you kicked me out!” Being angry he was refused to answer No. 27. Those who did not answer one or more of the questions or answered NO, were designated as “No No” boys and sent to Tule Lake in mid to late 1943.

My Mother, having just had a child, did not want to be separated from my father so they all went to Tule Lake. In Tule Lake my Brother was born in mid 1945. My father had been separated from my mother at this time. My mother, sister, and brother were incarcerated in Tule Lake until March of 1946.

My father was taken away in early 1945 and sent to Bismarck, North Dakota and put into an INS Detention Center, incarcerated next to German and Italian Officers. It is ironic, because my father said he received his best treatment at the Bismarck camp because, unlike the WRA camps, the POW camps were regulated by the Geneva Convention and were required to meet a certain standard. Mostly they had warm rooms and the food was much better than in the WRA camps.

JVH: Why did they choose to repatriate?

HK: This is a long question to answer with multiple reasons, but I will try to summarize it. I don't think they really realized what they said when they said they wanted to repatriate. Much of why they decided was out of anger: losing everything they owned, put behind bars in prison, and losing their freedom.

My mother really did not have much of a choice if she wanted to stay with my Father.

My father, though, was ANGRY. He was angry for being kicked out of the army and sent home. When he got home he found his father had been taken away by the FBI. He asked the WRA if he could stay behind for one week to harvest the crop in the farm, but was denied. He went into incarceration wearing his Army Uniform.

While being incarcerated he was voted as Block Leader. While he was incarcerated he voiced his anger about being incarcerated, that “We” should not be here, we are AMERICANS, he was in the US ARMY. They had no right incarcerating us and force us to sell off everything we owned. Because of this the other young men – specifically the new and young JACL leaders – had my father removed as Block Leader. He later received numerous death threats.

While in Tule Lake, he was later threatened by “No No” boys because they saw him as a SPY for the “loyal” Japanese Americans because he had served in the US Army. He was constantly angry about his treatment by both the government and his fellow inmates. My grandfather, who was a leader within the Hoshi-Dan group, listed my father with his brothers as supporters of the group. Although my uncles were active within the group – my uncle Hiroshi was a bugler during the Hoshi-Dan marches – my father refused to be a part of it. But because he was listed by his father, he was sent to Bismarck for over a year and was separated from my Mother, Sister, and Brother.

While he was in Bismarck he chose to repatriate, and my mother and siblings went along. By the end of the War he wasn’t given a chance to change his mind about repatriating and was sent to Japan. The entire family, with about 5,000 others, were stripped of their US Citizenship, despite having been born in the US and were US Citizens.

JVH: Why did you become stateless when you were born in Japan?

HK: In Japan my parents were not considered Japanese Citizens since they were born in the United States. Since the US Government had stripped them of their US Citizenship, I was ineligible for US Citizenship. So when I was born in Japan in 1948 I was considered “stateless” like my parents.

JVH: What was it like in Japan?

HK: I do not remember much about growing up in Japan. But I remember my parents feeling conflicted about their identity. After 6 months of being in Japan, the US occupying forces met with my Uncle Isao and spoke with him and my Father. They were hired by the Army Corps of Engineers because of their linguistic skills and worked with them during the occupation. He had the opportunity to send me and my siblings to the American Army School, but instead sent all of us to Japanese schools in the neighborhood. At home, my parents never spoke English to us so the neighbors would not think that we were from America. My parents wanted no one to know we were once American.

In 1955 my parents hired Wayne Collins from San Francisco to represent my family to regain their US Citizenship. In October 1956, we returned to the United States and became Americans again. As soon as we got off the ship in San Francisco, my parents suddenly only spoke to me in English. When I came to the U.S., I didn’t even know how to say the ABC’s or even to say hello. It was like that for another year. When I started school in the U.S. I was eight years old and I was placed into first grade – 2 years behind the others – because I could not speak English.

JVH: When your family returned to the US in 1956, were they accepted by other Japanese Americans?

HK: To my knowledge I think they were. We came to San Jose first and lived with my uncle’s family at their farm until my parents were able to rent a home in Palo Alto. Because we were with our family the transition wasn’t so difficult. Also the first home we rented was from a Chinese American family and we were accepted there as well. We joined the local Buddhist Church so we were also around other Japanese Americans, and as long as we did not talk about the war experience and having been in Japan, the others did not know.

JVH: Did your family talk with you about their experiences during your childhood? Did they talk about it with other members of the community?

HK: So my father and mother were very vocal about the experience. We heard them tell us many stories of being in the “Camp” as they called it and their experience after the Pearl Harbor attack. Whenever WWII came up, my father would go on and on. My mother would talk about how her neighbors were shot at as teenage kids. She told us once that a mother’s newborn baby died in her arms after arriving at Poston because it was too hot and she was unable to nurse the baby and there was no medical help. Another incident my father would tell us was when a Mr. Okamoto was killed at Tule Lake. We were lucky in a sense because I knew many stories and knew that they were in a concentration camp. Growing up many of the Sansei’s (third generation) Japanese Americans knew VERY little about the Camps. They knew which camps their parents were in, but that was it. Most families did not talk about their experience.

As for the general public, my Caucasian friends knew nothing about the incarceration experience. I got into an argument once when I was in high school with my best friend’s father about my family’s experience. He said we were all put in camps for our protection.

JVH: Do you share your story with the community? What is your message?

HK: I have been giving talks for over 15-20 years at high schools, middle schools, junior colleges, and at Sonoma State University near where I live. I am currently the Chair of the Oral History committee of the Sonoma County JACL Chapter that speaks to the public.

In the last ten years, I usually presented two messages: first, to know about the incarceration in order to avoid repeating it. The second is that individuals can make a huge difference. Although there was significant racism on the West Coast spread by the white community, a number of people stepped up to make a difference. I remember one family went to a Japanese American home and stayed there to make sure no one ransacked it. While the family was in camp, the white family harvested the crop, sold it, and saved the profits for the family until they eventually returned. Stories like that help to show people can help when times seem desperate.

With the current president, my message at talks is to show what happened 75 years ago to my family is happening now. Refugees coming from Central America are being separated at immigration camps just as the Issei were separated from families – like my own by the FBI. I recently spoke with the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors, and told them hardly anyone stood up for us; it is time that we speak up for the immigrants coming to this country for asylum.

* This article was originally published on Nikkei West on January 25, 2020.

© 2020 Jonathan van Harmelen