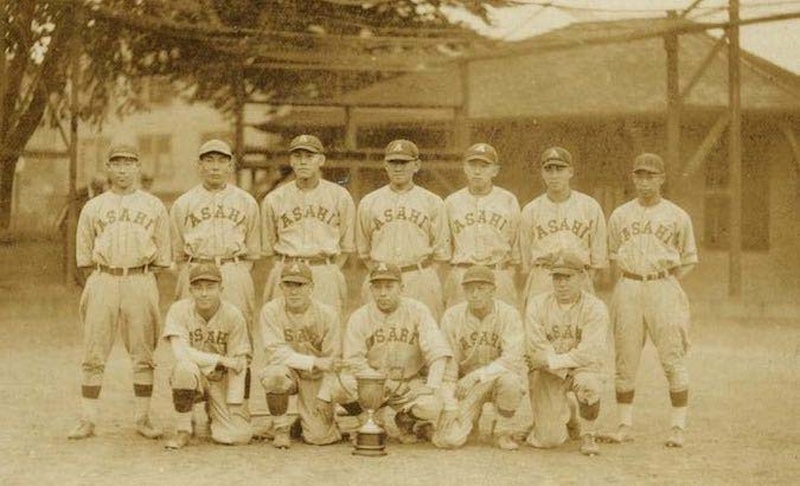

In 1930, Vancouver’s Asahi baseball team won the Terminal League Championship for their second time. Thereafter, Asahi won the championship of the Burrard League three times straight starting in 1938 before coming to a halt after the Pearl Harbor attack, after which the members were sent to road camps, internment camps, or POW camps.

The whole local Japanese Canadian community was into the baseball craze. It was a decade that started with the world crisis and ended up in war crisis—Nikkei fishermen were deprived of their fishing licenses, the racism became rampant as the imperial Japanese army intruded deep into China. It pressured Nikkei community in many aspects of their life. Yet, apparently teenage-Niseis studied hard at school and they did try to enjoy their sporting life as much as they could.

In 1931, Canada’s Federal Government in Ottawa granted the right to vote for Japanese veterans of the First World War. Japanese students of the University of British Columbia formed a Japanese Student Club and started discussing the systematic racism that they were facing and they tried to find the possibility of franchise being granted. It was because they had been brought up in the belief of democracy and fair play.

One of the young Niseis who enjoyed every sport was Shozo Miyanishi (February 1912–July 2006). He used to drop at my office of the Nikkei Voice when he was in his early 90s and enjoyed talking about his pre-war sporting life. For him, chatting freely in Japanese must have been a “relaxing” and “refreshing” time, while, for a community news editor like me, it was a precious and invaluable oral history class. He was a Kika Nisei or 帰加二世 who was born in Canada and was sent to Japan for their education. (note Kibei Nisei 帰米二世 refers to Japanese Americans who were educated in the same way.)

Shozo, born at 2024 Triumph Street, Vancouver, was sent to Japan for education at the age of six. He lived in Maibara-cho, Shiga Prefecture until he finished third grade or so when he joined his uncle’s family that ran an exclusive restaurant called Kimparo to finish his higher elementary school (grade eight) in Zeze, Shiga Prefecture. He boasted that he had been called “Bocchan,” an honorific nickname for a boy. Shozo’s smiling face sure gives us an impression that he was from a decent family, who grew up enjoying every kind of sport. He showed me the photos he had taken in prewar days, giving his comment on every photo. His talk went on and on and eventually, we decided to set interview sessions rolling the cassette tape.

The following article was originally published in the Nikkei Voice (Japanese section), July/August, 2001 issue. Then, in 2018, for the 13th anniversary of his death, his fourth child Ron and I, former Japanese editor of the Nikkei Voice, worked on its revised edition adding more information together with some comments from Shozo’s second child, Shirley.

* * * * *

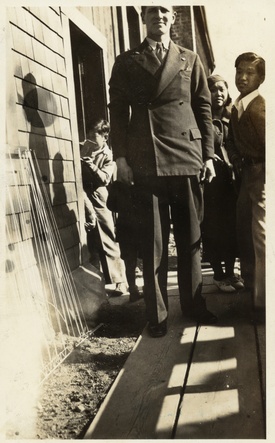

Shozo had brought a strange photo in which a towering white man dressed in a fine double-suit walking with his head a bit downward, but the top part of his head is out of the frame; it’s obvious that the photographer had hastily shuttered the camera to catch the sight of this tall guy passing by. This tall gentleman was the rookie baseball pitcher of Japan’s professional league, 19-year old Victor Starffin (1916–1957), a Russian political refugee in Japan. A very rare photo indeed.

Victor Starffin

In 1935, Starffin was in the newly formed “The Great Japan Tokyo Baseball Club” that toured North America; the team had two games with Vancouver Asahi at Con Jones Park Stadium (currently known as Callister Park) where the Asahi lost both games. Shozo hastened to take a picture of Starffin when the game started. “Starffin was a huge guy indeed.” It has been said that the rookie pitcher did not have good control but that he pitched at over 150 kph (100mph).

He was the only son of a White Russian who had been loyal to the Tzar. Thus, they had to escape from their home country when the Russian Revolution took place in 1917. They eventually settled in Asahikawa in Hokkaido, Japan in 1925 where Victor found his talent in playing baseball taking advantage of his oversized frame. At the age of 17 in his junior high school baseball team, he proved that he could become one of the best pitchers in Japan. When the media made him famous publicizing the news stories on him, the newly formed professional baseball team approached him and forcibly made him quit the school to join the pro-baseball team. According to the NHK’s TV documentary titled Baseball Was My Passport, the owner of the All Japan team, Matsutaro Shoriki (former head of the Metropolitan Police Board in Tokyo and the president of Yomiuri Newspaper company), aware that Starffin was a refugee from Russia, threatened him by suggesting that if he would not accept their offer, his family might be deported to Russia.

After the Russian Revolution, it was said over 2 million Russians escaped from their homeland. Thus, there had been no other choice for him but to live in Japan as a refugee who tried to assimilate into Japanese society but was never accepted. During World War II, he was excluded from the military service but instead was confined leniently in the village of Karuizawa together with other foreigners. There he became depressed and addicted to alcohol. After World War II, Starffin was back in uniform but was not the fastball pitcher he once was. He soon retired and at the age of 41, he died crashing his car into a train. He was on the way to attend the reunion of his junior high school. All his life, he was an “outsider” with no place to fit in and no ethnic identity. In his “hometown,” Asahikawa, the public baseball ground is currently called Starffin Stadium in his honor. Many prewar Niseis in North America share his anxiety and isolation to some extent.

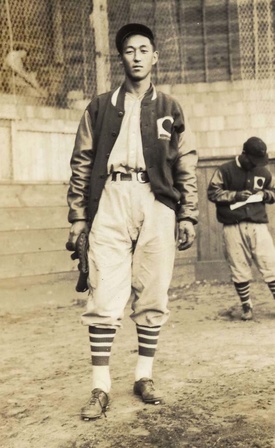

Jimmie Horio

For the prewar baseball players of Japanese descent overseas, it was an impossible dream to play in Major League Baseball. There was a huge wall of racism. It was 1947 when we saw the first black American major leaguer, Jackie Robinson (1919–1972). The career of a Nisei Hawaiian Jimmie Fumito Horio (1907–1949) was all the way a struggle against racism. Yet, he courageously went to play in the semi-pro league in California, enduring the hate speech thrown at him from the audience. But then, a Japanese professional league that was founded in 1934 approached Horio and invited him to Japan. Shozo’s photo shown here was taken when Horio came to Vancouver to play as a member of All Japan team in 1935. After the tour, he continued to play as a centre fielder for the Yomiuri Giants. But it was not before long when he sensed the danger of war; he rushed back to Hawaii just before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Had he stayed, he might have been drafted for military service in Japan.

To my question of “What would be the most popular sport among the Niseis aside from baseball?,” Shozo answered, “Rugby was quite popular, and we had ski club, swimming club, and more.” “Rugby” was an unexpected answer.

The photo Shozo took shows when the All Japan rugby union team visited Vancouver to play against the British Columbia Bears on September 24, 1930 at Brockton Oval in Stanley Park: they tied the game at 3–3. However, the rest of the six games were taken by the All Japan team. Considering the difference of body size, their technical level must have been way beyond that of the Asahi baseball team.

Fuji Ski Club

Nisei Canadians started a swimming club in 1930, then, in 1933, Fuji Ski Club was founded, which was allowed to join the Eastern Canada Ski Federation. Shozo said, “We had our own club house on Grouse Mountain. Nisei mountain climbers began to enjoy skiing in winter by renting the ski gigs. But renting it each time cost too much. Then, they got an idea of building a club house by themselves. Five or six founding members got together and recruited 30 members right away. A guy named Ozawa who ran a shoe store on Powell Street, where Japantown was located, was appointed as the president. I myself worked as the secretary.”

They built their own log house by leasing land owned by the British Columbia government. Carpenters consisted of five, or six Anglican church members from Shimane Prefecture. “They stayed at a nearby white men’s cabin and built it within a month of November. We also helped them carrying logs on weekends.”

Under the pressure of global depression in the early 1930s, Nisei workers must have worked at sawmills and factories on weekdays and yet, they went all the way to the mountain for skiing. Gathering for sports must have been an invaluable socializing time for the young Niseis.

The Niseis in the group photo taken in front of their own clubhouse look all cheerful and radiant. It brought my attention to a woman standing alone at the entrance of the log house. “She looks like the daughter of Tenning-san” said Shozo.

*This article was published in the Japanese section of the JCCA Bulletin as a 4-part series in 2019. The above English edition was rewritten and translated by Yusuke Tanaka in collaboration with Ron Miyanishi. Photos are courtesy of the Miyanishi Family.

© 2020 Yusuke Tanaka