As the war between the United States and Japan approached in 1941, the states of Baja California, Sonora and Sinaloa had a population of Japanese workers that numbered around two thousand people. By then, immigrant communities were already fully established in different cities and towns and played a very important role in the production of fish, vegetables, cotton, and various commercial lines.

The arrival of this large number of immigrants dates back to the first decade of the 20th century. The first wave came to work in the important copper mine of Cananea, Sonora. Another important group was hired by North American companies that needed numerous workers to build the various railroad trunks that would link Mexico and the United States. Another wave was concentrated in the Mexicali Valley, a place where they dedicated themselves to opening and preparing agricultural fields, in the midst of the revolutionary struggle between 1911 and 1917, which would give way years later to the great cotton emporium that would export large quantities of this fiber. to the United States and Japan.

In the following decades, thousands more workers continued to arrive for two reasons: First, due to the economic boom of the region and, secondly, due to the insertion of the Japanese communities that were already solidly established in Mexican society. These elements allowed immigrants to call their countrymen to start a family or to work in Mexico.

One of these new immigrants was Mitsuo Akachi who arrived in the region in 1927. Before emigrating, Mitsuo worked in a factory but understood that with this job he could hardly improve the living conditions of himself and his large peasant family. Akachi was born in 1908 and was attracted to Mexico by the news that immigrants sent in which they described the economic success they had achieved in this country. The Japanese had transformed themselves from poor workers into small, medium and even large merchants by managing to save and accumulate a small amount of capital.

Akachi had barely turned 19 years old when, along with three other young people, he traveled to Mexico. The four immigrants arrived by boat to the port of San Francisco and from there they moved to the Mexican border where they entered through the city of Nogales, Sonora. By that year it was already impossible to settle in the United States because American President John Coolidge had signed a law based on race in 1924 to prevent any Japanese citizen from immigrating to that country.

All these waves of emigrants leaving Japan were linked by peasant networks that allowed the flows of workers to be organized and supported based on the emigrants' place of origin. In the case of Mitsuo Akachi and his companions, they all came from the Nagano prefecture and were invited by their countrymen who were already firmly established in Mexico.

Upon entering Mexico, Akachi moved to the city of Huatabampo, Sonora, where he worked odd jobs. Later to the town of Los Mochis, Sinaloa due to the economic boom that that region enjoyed due to the important growth of the sugar mill and the growing cultivation of various vegetables. In this small town there were already other Japanese who advised Mitsuo to open a “refreshment shop” in the market; that is, a small stand where he prepared fresh water from barley, hibiscus and other fruits; drinks that were highly demanded by consumers due to the intense heat characteristic of that town.

In 1931, Mitsuo met a young Mexican woman, Concepción Robles, with whom he fell in love immediately, marrying that same year. Since then, the Akachi would work hard and successively open various businesses that would leave a deep mark on the commercial life of Los Mochis.

The Japanese immigrant community was already fully established in this place. They were owners of small, prosperous businesses such as nixtamal mills and grocery stores. Mitsuo, for some time, collaborated with one of his countrymen, Mr. Kuninosuke Akachi, who owned a nixtamal mill located next to the market. This business was so successful that it allowed this Japanese man to return to Japan enriched along with his entire family in 1937. 1

Mitsuo Akachi also worked with an American merchant, Charles Hay, who recognized in the Japanese great responsibility and capacity to the point of making the decision to transfer the grocery store to him. The North American considered that Akachi would maintain the business successfully and would pay him the remaining part of the transfer debt that they both decided would be paid in installments. The store called “The Mountain” opened at 5 in the morning and closed at 10 at night; The couple worked very intensely to sustain the business and manage to pay the debt.

The couple not only managed to pay off the store's debt but also managed to raise a capital of 30 thousand pesos, money with which they set up a store in 1940 dedicated to haberdashery, stationery and the sale of novelties. The haberdashery, called La Violeta , located on the central corner of Leyva and Juárez streets, was a success, because in addition to the personalized attention of the owners, it had everything that customers requested, even imported merchandise. The year 1941 came with very stimulating news for the Akachi, because after 10 years of marriage, they would receive their first daughter, of the four they would procreate. The end of that same year, however, ended with bad omens due to the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States.

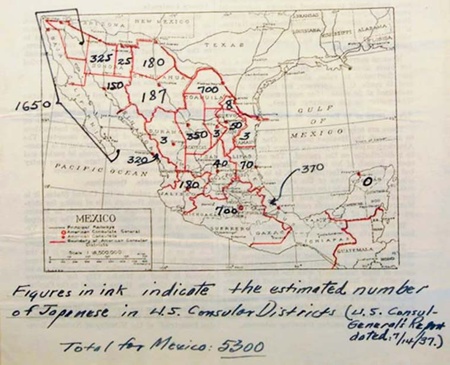

At the beginning of 1942, Mitsuo Akachi received the order from the Mexican authorities so that, along with all the immigrants living in Los Mochis, he moved to Mexico City. The Japanese would be concentrated in this city so that they would be closely watched. The North American government was the one that requested that the Mexican government immediately concentrate the Japanese who lived along the entire border, since it considered them, according to its criteria, very "dangerous" people with the capacity to carry out sabotage or even being part of an “invading army.” The FBI and the United States consulates, installed in the various cities of Mexico, had been collecting information for years on the number of immigrants, place of residence and economic activities to which they were engaged.

The first months of 1942 were really sad and painful for the Akachi. Mitsuo was forced to abandon his wife and newborn daughter. Concepción was in charge of tending the haberdashery alone so that there would be no lack of sustenance for the entire family. Within this tragedy that all immigrants faced, at least Mitsuo, being married to a Mexican woman, did not have to undersell his business and move with the entire family to the concentration places as happened with the rest of the Japanese families.

In Mexico City, concentrated communities were grouped in different neighborhoods of the city. Mitsuo moved with a large group of Japanese to the Tacuba neighborhood. In this area, the Japanese opened small stationery and grocery stores. For children who were already of school age, the community organized to rent an old house and create a place where the children, in addition to the public school they attended, could continue their studies of the Japanese language and other activities.

The recognition of work and honesty that the Japanese workers had managed to forge in Los Mochis and throughout the state of Sinaloa, allowed the state governor, Colonel Rodolfo Loaiza, to intervene to request the Secretary of the Interior, Miguel Alemán, to return to the immigrants with the commitment that the state and municipal authorities would take charge of monitoring them.

Thanks to this effort carried out by the governor who had the approval of the same population, Mitsuo and other concentrates managed to return to Los Mochis in 1943. The support and attitude he received from Mexicans in general made Mitsuo feel an integral part of Mexico despite the breakdown of relations between his native homeland and the country that had received him. Since then, Akachi began to consider processing his nationalization as Mexican, a status that was granted to him in 1956. By then he already had four children and had opened the first department store in Los Mochis that had a great presence in the lives of and the history of the city.

Mitsuo Akachi rooted strongly in the country that received him. For this reason, he reiterated that, although he was not born in Los Mochis, he felt an integral part of this place where he managed to build a place where he could live better and create a family. Mitsuo did not stop working until he was 94 years old when he died. Los Mochis was the place where he decided his remains would remain along with those of his wife who died at the age of 99.

Note:

1. The story of this family can be read in “ Jesus Akachi: The life and contributions of a Nisei to Mexico ” (October 4, 2016).

© 2020 Sergio Hernández Galindo