“The exhibition title evolved from Sisters to Tashme Sisters because both of them began belated examinations of their origins in an internment camp and the significance of their upbringing in a post-war JC family. However, with the exception of a couple of paintings Barb produced for this exhibition, there is no evidence of this background in their bodies of work. For me, this exclusion deepens the fascination with the richly dissimilar paintings they make.”

— Bryce Kanbara, Tashme Sisters exhibition curator & owner of You Me Gallery in Hamilton, ON

“Sunshine Valley,” sounds like a place that should possess idyllic, pastoral splendour, not the former BC site of an internment camp. Tashme, the site of the former internment camp, never existed, was never an incorporated village or town and for all intents and purposes, has slipped into obscurity, a topic for academics to parse and ponder about.

When I made the trip out to Tashme last summer with my pal Brad, I saw that it hasn’t really changed much since the last time I visited a couple of decades ago: a collection of trailer homes, tents, and cabins situated in a nice valley. Now a summer resort of sorts. It’s abundantly clear to me that were it not for the extraordinary efforts of Ryan Ellan, a non JC (Japanese Canadian) who setup the Tashme Museum on the site there would be little there to signify that it was a prison camp.

Ryan, a sign maker/graphic artist from Steveston has taken on this mammoth project as a tribute to the JCs who’ve made an impact on him. In August, he was in the midst of moving the old school house to a location closer to the museum.

When I was there, I imagined seeing the place through the eyes of my old friend, filmmaker and former Nikkei Voice newspaper editor Jesse Nishihata: “What would Jesse think about this?” I am sure that he would be impressed by Ryan’s noble undertaking. With his critical documentary filmmaker’s eye, though, I can imagine him being irked somewhat by something palpable that is missing. But what, exactly?

Viewing the National Film Board documentary, “-- of JAPANESE DESCENT” an Interim Report (1945) again, directed by O.C. Burritt and accompanied by a bouncy, happy soundtrack. The propaganda piece takes a rather patronizing look at us. We are portrayed as a jolly, smiling group of brown exotics meant to reassure white Canada that we “Japanese” (Japanese Canadians was never used) were obedient and content to be “prisoners” (that word was never used) living in swell looking “homes” (“shacks” was not used either). Words do matter. I imagine that the average white Canadian of conscience seeing this as a pre-movie newsreel in 1945, might have gone home feeling reassured that all was well.

After all, didn’t the narrator reassure us:

“It should be made clear that Japanese residents in these towns are not living in internment camps. Travel between towns in the same group is not restricted. These relocated people should not be confused with those who were dangerous or had subversive tendencies and who were arrested and interned by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police at the outbreak of the war with Japan.”

The internment camps were portrayed as being well served by a compassionate and caring government whose decision to “relocate” JCs had “resulted in a general improvement in the general health level” of JCs, referring to the tuberculosis sanitorium in New Denver. Do any of us in 2020 believe that internment was for our own good?!

Arriving back in Toronto, full circle, I was pleasantly surprised to see that the Tashme Sisters exhibition was at the art gallery at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre (JCCC). The title of the show prompted me to ponder about the importance of memory of internment, the importance of it as communities continue to struggle to define themselves, the importance of mining the memories of those who are left and, indeed, the importance of memory as it relates to how a community defines itself for future generations. Isn't this all worth fighting tooth and nail for?

Preoccupied with these ideas, I revisit Michael Fukushima’s NFB (National Film Board of Canada — yes, the same people who brought us --of JAPANESE DESCENT) documentary Minoru: Memory of Exile (1992) which begins:

Let our slogan be for British Columbia:

No Japs from the Rockies to the sea— Ian Mackenzie, Liberal Cabinet Minister, Vancouver,

1944 federal election campaign

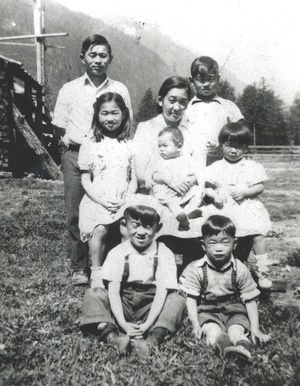

Even though Nisei sisters Mary, 74, and Barb, 76, have few personal memories of Tashme, the impact on them, their siblings and parents was profound. Uprooted from their Vancouver lives, cursed with the “Enemy Alien” label, herded on to trains, and put into internment camps, then east of the Rockies to Ontario where the Nishimura family settled on a farm in Cedar Springs.

* * * * *

MM (Mary Morris): I was born in Tashme after the war ended so cannot speak from any personal experiences of the camp, but my older siblings’ memories of Tashme are mixed. They remembered the bitter cold of the winters and the poor living conditions but they also have positive memories like playing with the other children and fishing in the creek. From conversations with my parents when they were alive, they felt that life in Tashme was tolerable since the family was always together and the internees helped each other out within the camp.

I can imagine, though, that the four years in the isolated, confined conditions with little freedom and contact with the outside world must have been very difficult at best.

Can you talk a bit about your parents? What kind of people were they?

MM: My father, Kinsaburo Nishimura, was a confident, hard-working, resourceful man who emigrated on his own from Japan at the age of 18 to Vancouver, B.C.. As a child living only with his mother in Shiga-ken, he worked in the rice fields and later in a store sewing “tabi” socks worn in “geta” or wooden Japanese shoes.

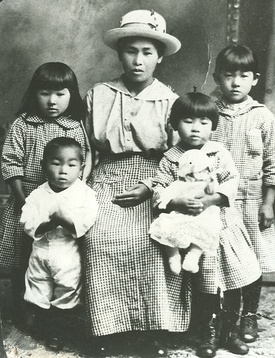

My mother, Yachiyo (Miike) Nishimura, was a reserved, kind, and generous woman who was born in Vancouver. Her parents emigrated from Kumamoto, Japan in the early twentieth century. Shortly after the U.S. and Canada declared war on Japan in December 1941, the Canadian government ordered the evacuation of all persons of Japanese ancestry from the west coast to 100 miles inland.

My father and most JC men were sent inland to build roads and camps. My mother’s inner strength helped her to survive those war years, especially the months in Hastings Park which was a group of livestock barns where JC families were kept while the internment camps were being built. With her four young children including a six-month old baby, my mother had to endure the appalling conditions of Hastings Park on her own.

Do you still have relatives there?

MM: Yes, I would think we still have relatives in both Kumamoto and Shiga-ken, but the family has lost contact with them over the years.

MBG (Miiko Barbara Gravlin): In 1965 during my Canada Council tenure in Japan, I visited my father’s cousin, Mitsuye and family in Osaka for three days. Our parents visited them in the late 1970s and may have reunited with other relatives. My youngest sister Gerry and husband George Hewson who obtained their black belts in aikido in Japan visited my Dad’s brother, Shinkichi, in 1980. He returned to Japan before the war and was stranded unable to come back to Canada. The Hewsons also visited my Mother’s sister, Hatsuko Tamura and relatives in Kumamoto, Kyushu where my grandparents came from.

Where did they live in BC? What kind of life did they have there? Work?

MM: Our parents lived in the Japanese community of “Little Tokyo” in Vancouver. When my father immigrated to Canada, he worked in a Matsushita department store but later worked as a cab driver and eventually for a bakery where my mother also worked. When war broke out he had his own bakery delivery business.

Can I get the names of your siblings?

MM: My siblings, in order of birth are John Kinichi, 1933; Joan Yaeko (Hamade), 1936; Stanley Mitsuo, 1937; Fred Fumio, 1941; Barbara Emiko (Gravlin), 1943; and Geraldine Yumiko (Hewson), 1950.

MBG: In 1975 when I married, it was less practised to keep one’s maiden name. My fine art resume published me as Barbara ‘Nishimura’ and to add ‘Gravlin’ seemed awkward. For a few years, I was in limbo signing some art works with “Nishimura or ‘Miiko’ or ‘Gravlin’.

My original idea for the art exhibit was called ‘Sisters’; Mary later suggested ‘Tashme Sisters’ in a discussion with Bryce Kanbara, the now former curator at the JCCC gallery.

Are there any family stories of life in Tashme that you can share?

MBG: My earliest memories are of lining up with Mother in Tashme to the laundry or bathing facilities. I remember the clatter of dishes and chatter of people having meals in a large hall. My dad told me, when I was born in 1943, my parents ran out of names for me so his butcher colleague named me ‘Barbara’ which didn’t endear me to the name.

One vivid incident occurred in a fall I had from our camp shack doorway. I remember being attracted to bright sunshine coming from an open doorway and falling out. My older brother recalls the sightings of white deer roaming the mountains. It became the subject of a small painting of Tashme at the JCCC.

MM: I do not have any personal memories of Tashme since I was born a couple of weeks after the war ended in September 1945. My older siblings remember the brutal winters when ice formed inside the walls of the tar paper shacks.

However, they also have pleasant memories as well, like the spectacular Rocky Mountain scenery which surrounded them, playing hockey, marbles, and judo with other children, entertainment in the form of movies and events at the high school, and a large “ofuro” (bath) about the size of a small swimming pool. They also remember bear sightings, forest fires, a measles outbreak and communal meals in a large hall. My father worked in the butcher shop and was paid $55/month.

Did your parents ever consider settling in BC?

MBG: I’m unaware my parents considered settling other than in Canada. All my JC relatives relocated eastward as well as my grandparents, Uhei, and Tachi Miike who went to work the Alberta sugar beet farms with my aunt and uncle, cousins. It was a harrowing choice as they worked under brutal conditions in an unforgiving climate.

What about going to Japan?

MM: I believe my father considered moving the family to Japan at one point since he was bitterly disillusioned by the treatment of the Japanese Canadians. It took my parents a year to make the decision to move east instead. Returning to their home in Vancouver was not an option, since the federal government ordered that all JCs could only move to Japan (most were born in Canada, my father having lived in Canada for 25 years) or eastward from British Columbia. Besides, all of the family possessions were sold during the internment years and there would have been nothing to return to in B.C.

© 2020 Norm Ibuki