3. Shoyu manufacturers in Chicago: Shinsaku Nagano

Hiroichiro Maedako, a socialist writer who lived in Chicago from 1907 to 1915, described Japanese production of shoyu in Chicago in his novel, Dai Bohu-U Jidai as follows. “Do you know that guy, Kimura? He has an office downtown and is in the food business. Kimura says he has good news and asks me, ‘don’t you want in on this?’ A lot of Japanese shoyu is now being sold in the US, but he says that shoyu can easily be made without using soybeans. To make a long story short, as the Japanese in Hawaii often do, you use dried fish and can produce a very similar color and taste as real soybean shoyu. Don’t worry, amateurs can’t tell the difference. Just mix it with real shoyu and sell it!”1

Kazuo Ito, a journalist who interviewed Chicago Issei in the 1980s also heard a similar story:

You import Kikkoman from Japan in barrels and mix it with your self-made “Chicago shoyu” and sell it as Kikkoman. You build a small shoyu brewery in the basement, and brew real shoyu with soybeans. A Jewish American invested his capital in the business and made a huge profit. The company was located near Wells and Clark.2

We really don’t know how much truth there was to their stories, but there was an Issei who produced shoyu in Chicago and became a very successful business man. His name was Shinsaku Nagano. Nagano was born in 1881 in Shizuoka and came to the US in 1906 as a practical trainee sent by the Shizuoka Tea Association. Nagano came to Chicago with a big dream of becoming a key player in the tea business.

In Chicago, Tomotsune Mizutani, who was assistant treasurer of the famous tea garden at the Columbian Exhibition in 1893, and later sent to Chicago as a representative of the Japan Central Tea Traders Association, had been promoting Japanese green tea since 1897 with a seven-year contract3 Mizutani established Gottlieb, Mizutany and Co. at 29 Lake Street in Chicago in 1901. He also started a Shizuoka branch of his company in 1906, mainly because Shizuoka is a center for tea manufacturing, then producing more than 60 percent of the annual tea production in Japan.4

We can assume that Nagano’s assignment in Chicago as a practical trainee of the Shizuoka Tea Association must have somehow been related to the Shizuoka branch of Gottlieb, Mizutany and Co. in Chicago. As if to confirm this assumption, Nagano started working as a clerk at Gottlieb, Mizutany and Co. after arriving in Chicago.5 After some time he started his own tea business, but had no success. Worrying about the uncertain future of the tea business, Nagano took a decisive step in starting a small shoyu retail store at 183 N. Wabash Avenue in 1911, Fuji Trading, which sold Japanese tea as well.6

In those days, sales of Japanese shoyu had begun increasing in the US. Exports from Japan totaled about $200,000 in 1908, but the amount increased to $300,000 in 1909.7 Most of the soy sauce used in daily life in the US was manufactured in the US, but some used Chinese soy sauce, imported from Nanking and Canton, which had stronger and thicker taste. Japanese shoyu was predicted to have bright future with a new market in the US if it could be exported more cheaply than Chinese soy sauce and adjusted to American tastes.8

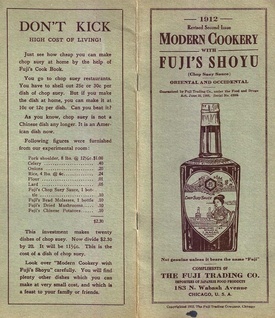

In addition to financial issues, the biggest barrier to Nagano’s business was exactly how to inform Americans of Japanese shoyu’s different but better taste than the products they had grown accustomed to. Nagano used every measure and opportunity to promote Japanese shoyu and devoted himself every day all day on its promotion. For a few years he struggled, but he reached a turning point in 1914 when World War I broke out. After that time, his business expanded exponentially.

Nagano’s wife, Kakuko, came to Chicago from Nagano’s hometown, Shizuoka, in October, 1915. Their first son, Shigeo, was born in Chicago the following year.9 By then, Nagano had started manufacturing shoyu at his own store and had extended his importing business to other goods, such as silk and china.10 In those early days, Mrs. Nagano’s contribution to Nagano’s success was tremendous. She wore kimono all the time, as they could not afford western dresses for her, and she worked hard in silence making shoyu in a dimly lit factory while Nagano stayed all day in the shop handling all the clerical work, sales, and deliveries.11 His shoyu was branded Fuji Chop Suey Sauce and could be purchased in a table-top bottle.12 The name “Fuji” for chop suey sauce was patented in January 1919.13 Although Kazuo Ito claimed in his story that Fuji shoyu was packed and sold in imported Kikkoman barrels because Fuji was not yet a well-known brand,14 there is no way of knowing the truth.

After the US entered World War I, Nagano’s business started growing by leaps and bounds because of the need to supply and feed the troops. After the war ended, Nagano bought a three-story factory at 116 Kenzie Street in 1919, and later bought a bigger factory at 22 E. Kenzie Street and moved there. The younger brother of his wife, 19 year-old Niro Mishiyagi, and the younger brother of Nagano, Jinshichi Fushimi, came to the U.S. in 1916 and 1917 respectively and helped with sales in Nagano’s business.15 In December 1921, a daughter, Grace Nagano, was born. Around this time, in October 1921 “Fuji Chop Suey Sauce” was patented.16

One of the reasons for Nagano’s purchase of bigger factory at Kenzie around 192217 was that he started manufacturing not only shoyu but also various other food products. Listed as Fuji Products were shoyu, bean sprouts, chow mein noodles, chop suey mixed vegetables, bamboo shoots, and water chestnuts.18 There were only three employees in 1921, but that number grew to 15 in 1924.19 And what’s more, Fuji Trading showed enough favorable growth to create branches in Hong Kong and Tokyo.20 Nagano also began a business importing food materials from Japan and China for the manufacture of shoyu in the US.21

4. Shoyu manufacturers in Chicago: Shinzo Ohki

In 1919, another man who was also interested in shoyu manufacture came to Chicago from Michigan. His name was Shinzo Ohki. Ohki was born in Kamakura in 1883 and came to the US in 1901. In Seattle, he met a Mr. & Mrs. Distan from Columbia City, Indiana and became their houseboy. Ohki went to Columbia City with them22 and graduated from Columbia City High School in 1907.23 Then he moved to New York. Working as a butler24 he graduated from New York University in 1911.25 Once back in the Midwest again, Ohki started his own tea and coffee business―Taka Tea Company (181 Bethune East Avenue) in Detroit.26

When Shinzo Ohki moved to New York, in a kind of brother-exchange, his four-year old younger brother, Chusuke, took his place in Columbia.27 Once Shinzo started his own business in Detroit, Chusuke helped him by becoming a delivery driver.28 Somewhat more than fifty Japanese lived in Detroit in 1916, and they established a Nippon Club, probably for mutual aid and entertainment. Shinzo Ohki got involved with the Club as an auditor.29

After a while, though, Ohki possibly felt negative about the future of the tea and coffee business in the same way as Nagano had. Besides Taka Tea Company, Ohki also started a soy sauce business and established the Oriental Show You Co. (20 Woodbridge Street) in Detroit30 to import soy sauce from China.31 After securing a Japanese driver who could deliver tea in a Ford automobile,32 Ohki went back to Japan in 1917, probably to marry, and while he was there visited Noda Shoyu in Chiba prefecture. Ohki learned traditional natural fermentation method of making shoyu in Noda and returned to the U.S. with his wife, Taka, in November 1917.33

Later, Ohki wrote a letter to Shinsaburo Mogi, son of Shichirozaemon Mogi (the Noda Shoyu family), who was active in the Chicago Japanese community as a successful businessman. Mogi came to Chicago with Fred Shigeyoshi Kitazawa around 1913 and started Yamato Importing Co. at 36 South State Street.34 Interestingly, their main business was not the import of shoyu, which was the family business, but wholesale import of silk and other textile items. Ohki expressed his impression of his visit to Noda as follows: “When I visited your factory in 1917, I was greatly impressed by the magnitude of your plant, as well as the advanced machinery you are using.”35

Did Ohki hear in Noda that Shinsaburo Mogi was in Chicago? In October 1919, Ohki came to Chicago with the Oriental Show You Co. The office of the company, which was then a wholesale grocery company, was located at 208 N Wabash Avenue.36 Saburo Iwanaga, brother of his wife, and Tojoio Sugawara as well, worked as clerks37 at the Oriental Show You Co. Ohki advertised shoyu imported from Japan in the newspapers. One of the ads read as follows:

AN OFFERING FROM THE ORIENT:

From Japan, the land of many wonders, comes this tempting new condiment to serve as a welcome surprise to guest, or make everyday foods more palatable at the family dinner.

ORIENTAL SHOW-YOU is a most zestful relish for meats, fish, soups, rice and vegetables. It can be used in cooking or served at the table as a sauce. …

Oriental Show-You at your Grocer’s … 35c…38

There must have been many competitors in the soy sauce market, as Ohki noted in the advertisement: “Notice the full name and spelling of ORIENTAL SHOW-YOU. Avoid imitations”. After a while Ohki not only imported shoyu from Japan, but also started to manufacture shoyu himself.

Around this time a newspaper article appeared, an article that might confirm the circumstances of the rumor that Ito recorded. The article reported that the ORIENTAL SHOW-YOU company complained that Fuji Trading was using a bottle for shoyu similar to the bottle Ohki used, and that resolution may be found in court.39

The 1923 Chicago City Directory listed Ohki as president of Oriental Show-You Co. and Shinsaburo Mogi as treasurer. Mogi was said to have made some investments in Ohki’s business40 and soy sauce manufacturing began at the address of the Oriental Show-You Co.41 The next year it became the Oriental Soy and Products Co.42 Mitsuji Kiyohara worked at Oriental Show-You Co. in Chicago as secretary.43

Kiyohara came to the US as a student in 1907; while studying at University of Michigan in 1917,44 he was the manager at the Imperial Soy Company in Detroit.45 Having learned that Ohki had moved to Chicago from Detroit, did Kiyohara follow him to look for new employment? At any rate, Kiyohara reported in the 1920 census that he was also an importer.

5. Beyond Boom and Depression

After the US entered World War I, the demand for Japanese goods and art decreased. But the restaurant business was on the increase among the Chicago Japanese.46 Naturally, the demand for shoyu must have also increased. Once Ohki started manufacturing shoyu in Chicago around 1922, Nagano had turned to a new business, canning, in 1924. Nagano, who had been paying close attention to the profitability of the canning business, moved to 317 West Austin Avenue in 1925, and transformed his company into a joint-stock corporation with circulating capital of $250,000 and more than forty employees, resulting in a top-class trading company, both in reputation and in reality.47 Canning vegetables imported from Japan and China48 was key to Nagano’s success.

On the other hand, the Yamato Importing Co. led by Mogi, who had helped Ohki of Oriental Show-You Co., moved to 305 W. Adams Street and dealt not only in clothing but also in wholesale dry goods.49 Yamato also exported bicycles to Japan.50 However in 1927, probably due to a decrease in business, Oriental Show You Co. (wholesale grocery) and Yamato Importing Co. (Japanese dry goods) shared the same address of 325 W. Monroe Street.51 Mogi left Chicago around 1927,52 Takemura also went back to Japan in 1927,53 but Kitazawa remained in Chicago to the last and took care of Yamato Importing Co. until it closed.54

In 1928, Ohki made his own return, back to the hometown of his youth in the U.S., Columbia City, Indiana, and restarted manufacturing shoyu and noodles there with capital of $75,000 and thirty one employees which brought in sales of $150,000.55 Ten years later, as of the end of December 1939, his Oriental Shoyu Company employed fifty Americans in the manufacture of shoyu and various other foods, and the company’s sales reached $270,000.56

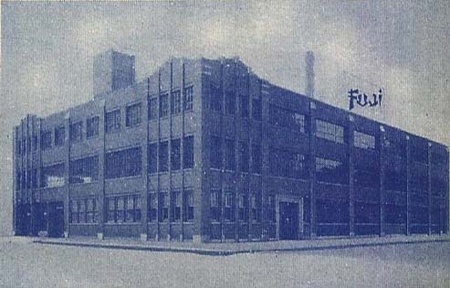

Who stayed in Chicago to the last and kept manufacturing shoyu? Shinsaku Nagano did. The proof that he realized his dream of having a business big enough to occupy a whole block for his own building can be found in the letterhead Nagano used in 1929: “Fuji Trading Co., Importers-Manufacturers, 311-317 West Austin.”57

In 1930, Nagano invested $500,000 in the purchase of a large plot of land at 441 W. Huron Street and built a new three story building with the latest equipment. Furthermore, he continued purchasing land in the neighborhood and expanded the building from three to five stories. Among the thirty-three employees of Fuji Trading, thirty were Americans58 and the annual sales of the company totaled more than one million dollars.59 Some Japanese in Chicago voiced their wish that a day would come soon when a Nagano Hall, a community hall for the people, would be built as Nagano had wished.60

Shinzo Koizumi, then president of Keio University in Tokyo, visited Fuji Trading in the 1930s. Koizumi, who had come to the U.S. to attend Harvard University’s tricentennial celebration, came to Chicago in October 1936. He had a guided tour of the Fuji Trading factory. According to his observations, a rather small three or four story building occupied almost an entire block and all food processing, manufacturing, and sales took place in the building. Fuji’s major products were Fuji shoyu and bean sprouts. They also manufactured and canned bamboo shoots there. Nagano employed about 50 people. Koizumi commented that as long as Chinese chop suey fit American tastes, the demand for Japanese products would be stable.61

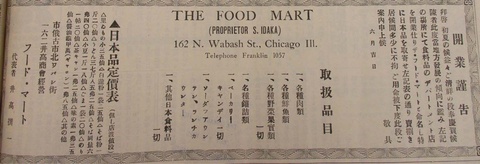

Of course, Fuji shoyu, made in the USA, had to compete with Kikkoman shoyu imported from Japan. Food Mart, a large grocery store at 162 North Wabash Avenue, which Senichi Idaka opened in June 1929, sold a gallon of Kikkoman shoyu for 1 dollar and 85 cents.62

As of the end of December 1939, Fuji Trading sales were $810,000. Compared with the Chicago branch of Japan Yusen Kaisha, one of the top Japanese shipping companies, with sales of $200,000, Fuji Trading’s record was far superior to others. There were only three Japanese employees, but fifty three Americans were working there.63 With such a large American work force Fuji Trading might be called an American company instead of a Japanese one.

It has often been said that Japanese and Japanese Americans could not find employment outside their ethnic communities on the West Coast in prewar days. But in the Midwest, in places like Chicago and Indiana, there were Japanese who built their own factories and hired many Americans.

According to the 1940 census, Shinsaku Nagano was already 58 years old, and the daily management of Fuji Trading had been taken over by Yoshi Miya (AKA Y. S. Miya) or Saburo Miyagishima, Nagano’s brother in law.64 Miyagishima was born in 1903 in Shizuoka, and came to the US with his future wife in 1922. He had helped in Nagano’s business since then.65

Notes:

1. Maedakoh, Dai-Bohu-u- Jidai, page 56-57.

2. Ito, Chikago Nikkei Hyaku-nen Shi, page 224.

3. Chicago Tribune, June 29, 1897.

4. Nippon Cha-Boeki Gaikan, page 160.

5. 1908 Chicago City Directory.

6. 1912 Chicago City Directory.

7. Nichibei Shuho, July 30, 1910.

8. Nichibei Shuho, April 20, 1912.

9. 1920 census.

10. World War I registration and 1920 Census.

11. Nichibei Jiho, January 3, 1931.

12. Chicago Shimpo, September 19, 1951.

13. Commissioner of Patents Annual Report 1919, No. 20491.

14. Ito, Shikago ni Moyu, page 166.

15. 1920 census.

16. Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office Volume 294, No. 23922.

17. 1923 Chicago City Directory.

18. Letter head, Ise/Zimmermann family collection.

19. Kaigai Nihon-jin Jitsugyo-sha no Chosa 1921, 1924.

20. Letter head, the Ise/Zimmermann family collection

21. Nichibei Jiho, October 13, 1928.

22. “Shinzo Ohki: Whitley County resident shares her discovery of a local legend,” Talk of the Town -Whitley County: Positive News in Whitley county (Posted on Oct. 11, 2019)

23. 1909 School Year Book-Columbia City High School, 1907.

24. 1900 Census.

25. Who’s Who in America, 1922.

26. Nichibei Shuho, March 10, 1917.

27. 1910 census.

28. 1912, 1914 Detroit City Directory.

29. Nichibei Shuho, February 12, 1916.

30. Washington, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1965.

31. History of Shoyu, page 9.

32. Nichibei Shuho, March 10, 1917.

33. Washington, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1965.

34. 1914 Chicago City directory.

35. History of Shoyu, page 807.

36. Nichibei Shuho, October 18, 1919, Chicago Telephone Directory, October 1919, October 1920.

37. 1920 census.

38. Chicago Tribune, March 13, 1920.

39. Nichibei Jiho, April 10, 1920.

40. Ito, Chikago Nikkei Hyaku-nen Shi, page 193.

41. 1923 Chicago City Directory.

42. Chicago Telephone Directory, June 1924.

43. 1923 Chicago City Directory.

44. 1917 School Yearbook.

45. 1917 Detroit City Directory.

46. Nichibei Shuho, May 11, 1918.

47. Nichibei Jiho, January 3, 1931.

48. Nichibei Jiho, October 13, 1928.

49. 1923 Chicago City Directory.

50. Ito, Chikago Nikkei Hyaku-nen Shi, page 193.

51. 1928 Chicago City Directory.

52. Ito, Chikago Nikkei Hyaku-nen Shi, page 193.

53. Nichibei Jiho, April 23, 1927.

54. Kaigai Nihon-jin Jitsugyo-sha no Chosa, 1928.

55. Kaigai Nihon-jin Jitsugyo-sha no Chosa, 1928.

56. Kaigai Nihon-jin Jitsugyo-sha no Chosa, 1939.

57. The Ise/Zimmermann family collection

58. Kaigai Nihon-jin Jitsugyo-sha no Chosa, 1931.

59. Nichibei Jiho, January 3, 1931.

60. Nichibei Jiho, March 29, 1930.

61. Koizumi, Amerika Kiko, page 204.

62. Nichibei Jiho, July 20, 1929.

63. Kaigai Nihon-jin Jitsugyo-sha no Chosa, 1939.

64. WWII registration.

65. 1930 census.

© 2020 Takako Day