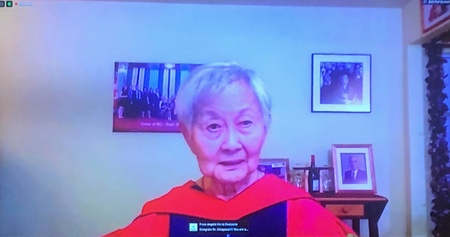

On November 26, 2020, in an official ceremony that needed to take place online because of the COVID pandemic, Keiko Mary Kitagawa received an Honorary Degree from the University of British Columbia. If the online ceremony lacked some of the pomp of the normal in-person ritual, the deep meaning of Mary Kitagawa receiving such an honour was not lost on those who took part in the ceremony through live streaming.

Among those was UBC President and Vice Chancellor Santa J. Ono, the first Japanese Canadian to serve as President of the university. Dr. Ono had been born in Vancouver when his father had been teaching at UBC, returning to become installed as UBC President in 2016, nearly ¾ of a century after UBC had unceremoniously removed 76 Japanese Canadian students in 1942. Those students were on many people’s minds as Mary received her honorary degree. She had been instrumental in the struggle to grant them the UBC degrees that they had been denied after their forced removal in 1942.

Mary’s recognition with an honorary degree in 2020 brought full circle to many moments, in particular to a pair of UBC ceremonies now linked forever. The online ceremony echoed the broken circle in the history of Japanese Canadians that had been closed in 2012 with the granting of honorary degrees to the 76 Japanese Canadian UBC students of 1942 exactly 70 years after their original expulsion.

In supporting the nomination of Mary Kitagawa for a UBC honorary degree, Dr. Stephen J. Toope, current Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University who had been President and Vice-Chancellor of UBC in 2012, wrote that Mary is “the architect of one of the most meaningful days in the century long history of UBC.” The series of reparation measures that the University took to pay tribute to the 1942 Japanese Canadian students, according to Dr. Toope, was a “difficult, and yet ultimately cathartic process” that UBC would not have undertaken “if it had not been for the tireless advocacy of Mary Kitagawa.”

Former President Toope detailed the process at length:

Mary Kitagawa provoked us to examine our present relationship to our past acts, and how our actions at this moment in dealing with what has passed is not a backward-looking exercise, but one that expresses the values and ideals to which we aspire for the future. I am certain that UBC would not have undertaken such a thorough, thoughtful, difficult, and yet ultimately cathartic process, if it had not been for the tireless advocacy of Mary Kitagawa for three long years. At the Tribute Ceremony held in May 2012, we were fortunate that through the indefatigable detective work of Mary and Tosh Kitagawa, along with the cooperation of many Canadians across Canada, the UBC ad hoc committee was able to find 21 surviving students out of the 76. In addition, Mary and Tosh were able to help the committee find descendants and family members of the 55 deceased students who could receive degrees on their behalf. As a result of this process of community crowdsourcing and dogged research, the special degree congregation in May 2012 became a powerful and emotional event. I was not the only witness among the packed audience that day who watched through watery eyes the parade of elderly men and women in their 90s marching slowly across the Chan Centre stage.

One former student insisted on getting up out of the wheelchair being pushed by his granddaughter, in order to proudly walk on his own to receive his long overdue diploma. We were witnesses to history that day: in remembrance of the historical wrong that had occurred 70 years hence--for which we acknowledged collective responsibility that afternoon--but also to an historical moment of hope and grace in grappling with the shared past that shapes us all. History was made that day in the honouring of the stories of endurance that each of those 76 students represented, as well as in the lives of the descendants there to witness this moment of recognition and redemption. For many who were fortunate to be there that day, the act of redemption was contained in the simple triumph of students finally attaining a goal long thwarted; but it also meant so much more. As many of the students expressed in the days and morning before the ceremony, they had lost ago lost any hope of completing the university degrees that they, and their long-deceased mothers and fathers, had so desired three quarters of a century before. Even as they received UBC degrees, there was little practical value to finally receive in the sunset of their lives the light they had deserved in the dawn of their days. Degree credentials and the doors that might have been opened 70 years before had long ago ceased to matter.”

Dr. Toope quoted one of those students, 88 year old Mits Sumiya, from his remarks shared on the Discover Nikkei Journal after the ceremony about how he had felt upon returning to the alma mater that had exiled him so long ago: “I saw Mary Kitagawa and her husband Tosh...Mary was carrying a big sign “UBC WELCOMES MITS SUMIYA.” I had never seen these people before but suddenly they were my extended family welcoming me home. A warm euphoria coursed through my veins and we hugged and we laughed and I felt home at last! This euphoria stayed with me throughout the week I was in Vancouver.”

Dr. Toope went on:

The redemptive act for me lay in the gift that the students gave the rest of us gathered there that day, a sense of hope that the wrongs of the past could in some way made right, even with the passage of so much time. This gift was made possible by Mary and Tosh Kitagawa’s tireless work on behalf of those 76 students whom they had never even met. Mary began her campaign because she believed that there had been a wrong that should be made right, and that this would be a “degree of justice” for those students. For UBC, the ceremony provided a way of finally welcoming home students we had been derelict in our duty to protect—rather than resisting the forces of bigotry and expediency, UBC had been complicit in destroying their sense of belonging at the campus they called home. This was the gift with which the Japanese Canadian students of 1942 graced us with that day in May 2012: that in their grateful appreciation of a return to the home they had lost, we regained a measure of the humanity that we ourselves lost on the day we exiled them.

It is notable that in an era when a number of formal apologies have been made by governments for historical wrongs in the past, almost none of the extensive global media coverage of the event mentioned the formal apology I made as President on behalf of UBC for what had happened to them seven decades before. UBC’s reckoning and recognition of our responsibility in 1942 became a minor part of that day’s events, subsumed by how the stories of the students’ journeys touched a universal chord in all of us fortunate to be there that day. This was the gift of redemption given to us by Mary Kitagawa in having the courage and fortitude to force us to live up to our own ideals.

The degree ceremony in 2020, eight years after the one in 2012, reflected the institutional legacies that Mary and Tosh Kitagawa’s tireless work helped create for future generations of students. Dr. Gage Averill, Dean of Arts, remarked in his support of the nomination of Mary Kitagawa for an honorary degree that permanent legacies resulted from commitments made by UBC Senate in tribute to the Japanese Canadian UBC students of 1942:

Mary’s campaign for the 1942 Japanese Canadian students was crucial to the creation of the Asian Canadian and Asian Migration Studies program (ACAM), and she has been one of the most dedicated supporters of the program since its inception. Indeed, in addition to participating in and guest speaking at different ACAM classes and events, Mary is also an active contributor to the program’s initiatives for public education and community engagement. For instance, in 2017, alongside a team of students, staff, and faculty from across campus, Mary stewarded the planning and implementation of a campus-wide Day of Learning to mark and reflect on the 75th anniversary of Japanese Canadian internment. The whole-day programming attracted more than 500 participants from across Greater Vancouver—many of whom would not have traveled all the way to UBC if not for Mary’s deep community connections and persistent efforts in promoting the event.

Unlike in many universities in the United States that have had Asian American studies programs and departments since the establishment of the Asian American Studies Center at UCLA in 1969, no Canadian universities in 2012 had a permanent Asian Canadian studies program. Since the founding of ACAM at UBC in 2015 and the creation of an Asian Canadian studies minor at the University of Toronto, the academic landscape of Asian Canadian and Asian migration studies has changed from disparate and often ad hoc courses to formal institutional presence, an important shift to counter the on-going marginalization of the histories and contemporary presence of Asian Canadian communities.

In his letter of support for Mary Kitagawa’s nomination for an honorary degree, UBC ACAM Director Dr. Chris Lee described Mary as “one of the most influential Asian Canadian leaders of our time,” stating that her “greatest legacy will be the individual students she has transformed — who will go on to transform the world in their own ways.” Indeed, the significance of Mary’s connections and contributions to UBC cannot be understood only through her campaign for the 76 Japanese Canadian students forcibly expelled in 1942, but “should be appreciated through the ongoing impact her advocacy and her life have on countless UBC faculty, staff, students, and alumni—and how they are each enriched and inspired to work towards a more just and inclusive society for all.”

Dean of Arts Gage Averill summed up the multiple letters of support from UBC students and alumni for an honorary degree for Mary Kitagawa:

Mary has also developed strong connections with the ACAM student and alumni community through formal and informal opportunities of engagement. In 2018, Mary co-taught ACAM 320A: The History and Legacy of Japanese Canadian Internment, in which she encouraged students to learn about and understand Japanese Canadian internment not only through academic research and scholarship, but also through survivors’ family stories and guest lectures from community members and activists. As the students point out in their collective letter of support, the opportunity to “learn from a community leader like Mary with her extensive knowledge in community organizing and social justice advocacy” was “extremely transformative.” The students also highlight Mary’s impact on their personal and community development outside of the classroom, as she and her husband Tosh have generously opened their home to students as “a space of gathering and community-building.” They have effectively extended the classroom into their homes in a deeply personal way and re-defined “engagement” in a way rarely seen in the university context. Over the years, along with her husband, Mary has built long-lasting mentorship and friendship with ACAM students and alumni, many of whom have come to view Mary and her husband as “community role models,” “knowledge holders,” and even “grandparents” to the ACAM community.

The impact of Mary and Tosh’s advocacy work reaches far beyond the University of British Columbia. In addition to being actively involved in community organizations such as the Greater Vancouver Japanese Canadian Citizens Association and research and public education projects such as “Landscapes of Injustice” at the University of Victoria, Mary and husband Tosh have also left a tangible mark in the public history of Canada.

In 2007, Mary noticed an announcement that the new Federal Government Building in downtown Vancouver was to be named after former Member of Parliament Howard Green, one of the leading proponents in the racist political campaign to remove Canadians of Japanese descent during WWII. Howard Green had been a principal architect not only of the removal, but also of the forced sale of the property and possessions of Japanese Canadians, arguing that seizing their property would leave them without a home to which to return, a process of permanent dispossession and exile that was much harsher and devastating than removal and internment in the United States.

Mary subsequently began a campaign to stop the building from being named after Green, and successfully rallied enough supporters to persuade elected officials to reconsider the name. The renaming committee eventually decided to name the building in honour of Douglas Jung, the first Asian Canadian elected to the Parliament of Canada and now the first to be recognized with the naming of a Federal building. The name change took place in 2008, after a year in which Mary’s determination and careful research persuaded countless people to actively care about the name of this building and learn about the untold histories of racial exclusion in Canada.

Mary and her family were among the more than 22,000 Canadians of Japanese descent who were unjustly displaced and incarcerated during and after the Second World War. Mary was only seven when she witnessed her father being taken away by the RCMP in 1942; the rest of the family were forcibly removed from their home on Salt Spring Island a few months later, and their family farm and properties were sold without permission.

After twelve long years of repeated forced relocation to different incarceration camps in interior BC and Alberta, Mary and her family were finally able to return to Salt Spring Island in 1954. However, their return was only the beginning of another long and difficult journey to rebuild their lives in the face of continuing racism. These early experiences of injustice shaped and informed Mary’s lifelong commitment to ensuring that stories of past wrongs are not only remembered, but also corrected and addressed through meaningful measures of reparation and action plans in the present. Indeed, Mary Kitagawa’s unequivocal advocacy for equity and justice has left an invaluable, transformative legacy in British Columbia and Canada.

Even before UBC granted an honorary degree to Mary Kitagawa, she had received several other honours, including being appointed to the Order of British Columbia (OBC) in 2018 “for her outstanding leadership and service in support of social justice, human rights, and historical reconciliation.” As her OBC biography described, the work of Mary Kitagawa and other tireless advocates against racism and injustice “has helped dismantle society’s systems of racial apartheid and legalized discrimination, create a more inclusive and just world, and demonstrate it is never too late to make right a wrong.”

History is never only about the past. When we think about what has passed, we always do it from a present moment that shapes the questions we ask and the answers we seek, and the legacies of the past live on in the ways we remember--and forget--those who went before us.

As a historian, I argue to my students that the great currents of history are borne by mass movements, social changes that reflect the aggregate actions of many people working together in concert or driven by larger shifts in economics and demography. As with many historians, I seldom argue for viewing historical change as the results of “great men,” seeing individuals instead as reflections of the broader changes that they often represent. And yet, even with the de-emphasis on the role of individuals, there is no denying that there are some people who nevertheless cannot be considered as anything less than significant historical actors who help change the world for the better.

As former President Dr. Stephen Toope stated: “If an individual’s broader impact on society is an important criterion for recognition by UBC through an honorary doctorate, Mary’s important role in helping reshape perceptions of our present relationship with our past makes her a deserving recipient.” Indeed, the legacy of Mary and her husband Tosh Kitagawa’s community leadership and advocacy extends beyond their cause’s immediate context, leaving profound and wide impact that continues to inspire people and institutions to recognize and reckon with the structural and personal responsibility we might bear for our shared pasts and futures. As an agent of change, Keiko Mary Kitagawa offers hope to us all that we can help reshape the legacies of the dark days behind us into better days to come.

* * * * *

Other Forms of Recognition Received by Keiko Mary Kitagawa

- 2019: Wallenberg-Sugihara Civil Courage Award

- 2018: Order of British Columbia (OBC)

- 2013: National Association of Japanese Canadian Leadership Award

© 2020 Henry Yu