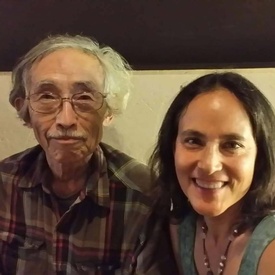

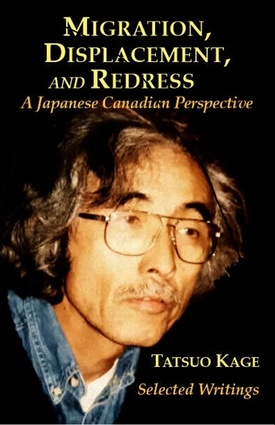

Reflections of a daughter on compiling her father’s book, Migration, Displacement, and Redress by Tatusuo Kage

About eight years ago, prompted by my mother, I started sorting through the piles of boxes and files in my father’s personal library study. This became an annual summer project. I found volumes of correspondence, committee meeting minutes, reports, articles, magazines, letters, and more. Digging through the archives, like a treasure hunt, I gradually organized my father’s original writings and memorabilia into several binders. One can grow accustomed to the people they live with, and eventually no longer surprised by their outstanding contributions: that is just my Papa, being Papa.

But when I was faced with the toppling stack of headlines about human rights breakthroughs, each headline having been years of dedicated work in the making, and when I read through the thoughtful and relentless articles, each promoting peace and understanding among us, my sense of responsibility as a global citizen and not just a proud daughter forced me to take action.

I decided to embark on sharing his collected works with the world. That initial housekeeping project evolved into a new publication that was successfully launched this season, entitled Migration, Displacement, and Redress: A Japanese Canadian Perspective. This work, the creation of my father, Tatsuo Kage, is for all of us, and so our family has gone to some lengths to present it to the community.

As a teenager I would peek into my father’s small, cluttered study, where his bookshelves were filled with titles related to Nazi Germany and ask him why he was studying Hitler. Typically, never taking his eyes off his desktop full of papers, he evaded my question, mumbling in Japanese, “Saaa ne…”, best translated as “Hmm, I wonder….” Disappointed, my burning curiosity had no choice but to leave the absent-minded professor alone until the next chance presented itself. And the next. One day, after many such failed attempts, he finally gave an explanation that stuck with me. “Since Japan was a close ally with Germany during World War II, I always wondered if what happened in Nazi Germany could also potentially happen with Japan, so I started researching.”

I remember my father periodically sitting on the floor of his home library with a paper cutter, glue stick, scissors, and scattered pieces of paper. He was editing and assembling the monthly newsletter, the old-fashioned way, for the Japanese Immigrants Association going back some 30 years or more. Every summer, I would find my father on the floor in the same manner, carefully labelling, cutting, matting, and pasting photos of some key community events, creating large display panels to be set up at the Human Rights Committee booth at the Powell Street Festival site.

During the 1980s in Vancouver, with his fellow new immigrants, my father organized and wrote scripts to be performed as skits for the annual Powell Street Festival – a downtown eastside park lit up by Japanese cultural events for a whole weekend. One summer, one of my teenage sisters was roped into playing the role of Wonder Woman for the skit while I was intrigued to see my father dressed up to play the role of Ultra-Man, a Japanese superhero in a popular TV show my sisters and I used to watch growing up in Tokyo, for which he wore a fitted swimming trunk over a greyish pair of tights! For an intellectual, he was quite an accessible person.

In 1992, my father invited me to participate in the Homecoming Conference. Elderly Japanese Canadian survivors of dispossession and internment during World War II, who had afterwards been forced to migrate from British Columbia to more eastern reaches throughout Canada and to Japan, came back to Vancouver for a summit on the whole community’s experience of migration, displacement, and redress.

My mother invited her Indigenous friends, Vera, Arlene, and young N’Kinka Manuel who shared moving poetry and traditional stories with the participants. Following their presentation, accompanied by my sister playing the taiko drums, we performed a bilingual storytelling show, blended with poetry and Japanese folk songs. While creating culturally relevant entertainment for the Japanese Canadian seniors, I experienced my own personal homecoming. Having spent my childhood in Japan, I now had the opportunity to celebrate and share my Japanese cultural roots. I appreciated this unexpected gift of reconnection which transformed into a ritual of intergenerational giving and receiving.

From the 1990s, my parents’ home became a meeting place and a regular lodging for various members of the Líl’wat Nation and many other indigenous leaders and representatives. My mother, a retired social worker, befriended many of these activists. Hearing stories of their struggles, my mother spoke highly of all her guests, admiring their courage to battle for their sovereignty rights.

Over the years whenever I journeyed home, I met so many fascinating individuals who would drop by to visit – those attending court hearings, appointments, or making their way to legal assistance in Vancouver. I witnessed enduring friendships that my parents developed with visitors from all over, sharing dinner time conversations, tea, and breakfast in the morning. There were times a group of friends from Mt. Currie, Líl’wat, needed lodging so they could catch a flight to Geneva and New York for their important United Nations conferences. In fact, Kerry Coast, the publisher for this book, was one of the people who joined the trips to these UN conferences, and has worked with and known my family for many years.

During those years, whenever I would call home, my mother would have endless news and stories of travelling visitors, and the going-ons of an involved household. And this is how I met the father of my four younger children.

One of my mother’s comments was planted deeply in my heart: “I am of colonial European ancestry; so one of my responsibilities is to do what I can to support the plight of Indigenous people who suffered so much through colonialism. This is the least that I can do.” Following my mother’s example, I have worked towards healing some of the damage of colonialism. Through raising my children in and as part of Indigenous communities, I have been privileged to be involved, and to learn some of the traditional arts and cultural teachings.

By 1997, I joined my parents, who were founding members, in the Japanese Canadian Community Association’s (JCCA) Human Rights Committee. Triggered by the cases of exploited Japanese workers and immigrant victims needing support and advocacy, my father proposed we hold bilingual workshops to help raise awareness about domestic violence and sexual harassment in the workplace. These workshops were the first of their kind for the Japanese Canadian community in Vancouver and my mother was instrumental in bringing in professional resource people to speak on these subjects which were especially unfamiliar to immigrant Japanese women.

I fondly recall of the few years I sat through JCCA board meetings and Human Rights Committee meetings with my father. At meetings, he was an excellent listener, and when he shared, he did so in a calm and practical manner respectful of all those around him. One of the projects I enjoyed was the Intermarriage Workshop series initiated by my father and the committee. Because of my interest in the topic, I stayed involved for five years, learning from the many discussions throughout the twenty workshops mentored by the cross-cultural psychiatrist, Dr. Fumitaka Noda, and engaging with other intercultural couples along the way. It was rewarding to see mostly Japanese immigrant women with their Canadian partners exploring common issues and questions creating a culture of peer support through these workshops.

*This article was originally published in The Bulletin: a journal of Japanese Canadian community, history and culture on December 4, 2020.

© 2020 Mariko Kage