During the Second World War, George Doi and his parents and siblings were imprisoned in an internment camp at Bay Farm in Slocan. After they were released, Doi’s father started a logging business in the Slocan Valley. Later, he worked for many years in the B.C. Forest Service locally. In Part One of his series on the internment camp, he described the events leading to the internment, and the family’s eviction from their home on Vancouver Island.

Here, in the second of a four-part series, he describes their temporary internment in Hastings Park, Vancouver.

* * * * *

It probably took me a week to get over my motion sickness but somehow I found myself moved into the Pacific National Exhibition (PNE) grounds, also called Hastings Park.

Here we were inside the Pacific National Exhibition grounds. This is where people came to have fun, laugh, and ride on the Baby Dipper or the Giant Dipper (roller coasters) and enjoy the carnival, but that was before we moved in.

The outer perimeter was secured by wire-fence with rows of barbed wire strung along the top. The Hasting street side - the part abutting the golf course – had a tall wooden fence.

Being surrounded by war news and branded as the enemy was shocking. To have our properties seized and then be evicted from our homes into the unknown was terrifying. When I look at wartime photos of the evacuees, I see nothing but shocked and bewildered looking faces. Not bitter or angry as one could expect but numbed and with a genuine look of despair. This was my observation of the adults, especially women, during my time in Hastings Park (and in internment camps).

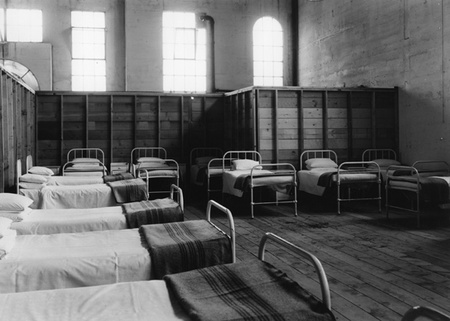

The building we were in was huge. The livestock barn was designated as the women’s building – boys under 16 were allowed to stay with their mothers. The Forum building was for males, 16 plus. The first thing that greeted us when we entered our building was the smell of urine, a pungent odor that smarted my eyes. The remains of animal dung and urine on the walls and in the troughs were still evident, even though everything was washed down and disinfected.

It took a while for me to get used to the barn smell. I would hold my breath and try to sleep but the overwhelming smell made me gasp. After a few hours I would be sound asleep from exhaustion.

To afford privacy, families hung army blankets between neighbours. Looking down from the top of my bunk bed, I saw a small elderly woman, kneeling on the bed and carefully counting the coins in her purse. Then, wiping away tears with her dress, she emptied the purse and started counting again. This was the same woman that had earlier wanted to give me a coin. But I hadn’t taken it. Some weeks later, I noticed her bed empty except for the straw mattress. I often wondered where she had been shipped to.

Late one evening I saw a young woman with an empty baby bottle frantically looking for a matron and I heard babies screaming in the far aisles. I knew that the news of milk shortage that I heard earlier had something to do with this crazy mess.

Sometimes, late at night when everybody was fast asleep and the eerie silence filled the darkness, I would hear the banging of pails in the laundry room. I imagined a woman finished washing baby’s diapers in the dim candlelight.

The mental anguish and stress were written on adult faces everywhere but I think those in the Women’s building suffered the most. With the families separated it was the wives who had to look after their children, be concerned for their education and their future. With no one to lean on or share their problems with, it must have being overwhelming.

I personally feel that only those who had gone through it could really grasp what it was like at the time. Anytime officials entered our barn, we would soon know and adults would rush out of their bed quarters to find out what news they might have brought. The future looked bleak yet they tolerated and carried on with their daily chores, living in harmony with complete strangers and not creating any disturbances. It was a depressing place but the strong Japanese culture being what it was in those days, I guess we just put up with it. (Even in internment camps we had resigned to whatever fate and destiny awaited us and didn’t make any waves or create violence. So, forcibly removing us from our homes into these camps and later dispersing us were easy tasks for the governments.)

I don’t know if others noticed how polluted the air was inside our building. When the sun rays beamed through the cracks in the roof, I saw all kinds of straw and other particles floating in the air, and I often wondered if it might affect our health.

When one person got a communicable disease we all had to line up and get anti viral vaccination. I can’t remember how many times I lined up to get the shots but to this day at least one such pockmark is still visible on my arm.

With the continuous flow of families moving in and families moving out, and with absolutely no news of what was to happen to us, we were just living day to day. According to Ken Adachi’s book The Enemy That Never Was (a comprehensive and well documented history of the Japanese Canadians) it stated that, “At the peak of its habitation, on September 1,3,866 persons were living there and over 8,000 passed through the Park at one time or another.” And the British Columbia Security Commission reported that, “.. a total of 1,542,871 meals were served during the operation of the Park at an average cost of $0.0933 per meal.”

What BCSC failed to mention was that all our meals, transportation costs, storage charges, internment camp costs were paid by us, the internees. The government sold our properties, shortly after we vacated, at a fraction of their value, then deducted all above costs and the net proceeds, if any, were deposited into the property owner’s bank account; but the government set the amount the owner could withdraw per month. I suppose this was to ensure that the families would support themselves and not burden the Canadian taxpayers. Those married workers in road camps had to send $20.00 of their pay cheque every month to their families in internment camps. They were paid 25 cents per hour.

Here is one small example of the minds of officials when disposing of Japanese Canadian properties: The husband and wife cleared their land of stumps and bushes, built a house on it and sold vegetables and strawberries. The government seized and sold their property. After deductions the owner received a cheque for $1.29. The equity the family built up over many decades represented their lifetime investment! It was so absurd and insulting that their son left the cheque pinned up on his kitchen wall, and I saw it.

Another example (from The Enemy That Never Was): “Shoji had bought 19 acres of land in the Fraser Valley village of Whonnock in 1931 under the Soldiers’ Settlement Act and then cleared and cultivated nine acres. In 1943, his land, a two-storied house, four chicken houses, an electric incubator and 2,500 fowls were sold, without his consent, for $1,492.59. After deductions for taxes and commissions, Shoji received a cheque for $39.32 which he promptly declined, claiming a loss of $4,725.02.”

Sgt. George Y. Shoji a twice-wounded veteran of Princess Pat in WW1 was interned in Bay Farm camp. I noticed he had lost one eye. There were two other war veterans in our camp.

I read that the first group of detainees arrived in Hasting Parks around mid March, 1942. We were there in April or May.

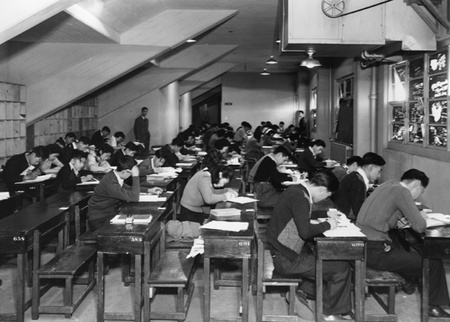

I noticed people moved about quietly but quickly. Their future looked extremely bleak. Their children’s education was a constant worry. The adults took the initiative to find places to hold classes and they themselves assumed the role of teachers. The class I was in was held on the bleachers in the Baggage building (Horse Show building). The noise from baggage being shuffled for storage for the in-comers and retrieval for the out-goers was constant and very disruptive but the teachers persevered and did their best.

Last days in Hasting Park…

All the time we were in the Park there was continuous movement of families moving in and families moving out. But towards August I noticed there were more and more empty beds in our building. We exited the Park in August or early September, 1942.

I don’t know if our parents were told where we were going but it probably didn’t matter, as most people wouldn’t have had a clue to any names outside of Vancouver or the Fraser Valley.

To be continued...

*This article was originally published in the Nelson Star in May 2017.

© 2017 George Doi