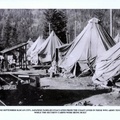

During World war II, George Doi and his parents and siblings were imprisoned in an internment camp at Bay Farm in Slocan. After they were released, Doi’s father started a logging business in the Slocan Valley. Later, he worked for many years in the BC Forest Service locally. In part one of his series on the internment camp, he describes the events leading to the internment, and the family’s eviction from their home on Vancouver Island.

* * * * *

It was 78 years ago that the lives of Japanese Canadians abruptly changed. At the time there were 23,303 Japanese Canadians living in Canada – mostly in coastal British Columbia, but there was also about 2,000 scattered throughout the country.

Our family — Mom and Dad and six children— lived in Royston, Vancouver Island, B.C. Dad worked in the coalmines in Cumberland for a short while. Then when a wildfire razed their small community in 1927 and destroyed most of the buildings, my parents moved to Royston and Dad worked for Royston Lumber Company. He worked in logging, eventually becoming a head faller. I had two older sisters but I was the oldest of the boys— nine years old at the time when our lives changed.

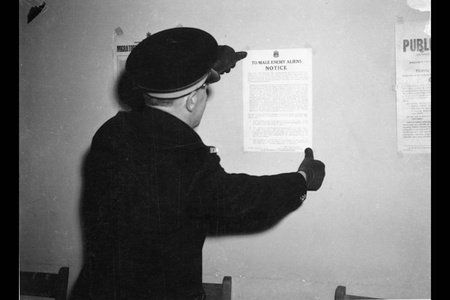

When the Pacific War broke out in December 1941, we were all branded as “Enemy Aliens” and forcibly removed from the 100-mile “protected coastal area.” We were given limited time to move out. Our baggage was limited to a certain number of pounds for adults and for children. The government’s British Columbia Security Commission (BCSC) was in charge of our removal and our entire possessions were turned over as ordered to the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property (CEAP) for “protective measure” only.

At this time I should mention that before our expulsion, various groups, politicians, etc. met in Ottawa to discuss national policy on the Japanese Canadians.

Under-Secretary of State Hugh Keenleyside didn’t feel a complete evacuation was necessary. And apparently, all of the civil servants were united in advocating that the Japanese not be interned. The army representative, Major-General Maurice Pope, Chief of General Staff told the Standing Committee, “From the Army’s point of view, I cannot see that they constitute the slightest menace to national security.”

At the meeting, the RCMP representative reported that the few potentially subversive Japanese had already been interned and that no further internment was necessary; he expressed no concern over the Japanese presence. The Navy Vice-Admiral stated that there was no problem, for all Japanese fishermen had been removed from the sea on the day of Pearl Harbour. (Above two paragraphs are from The Enemy That Never Was, a documentary by Ken Adachi.)

The Standing Committee views had always been anti-Japanese. With intense pressure from politicians and racist groups in British Columbia demanding our removal, the committee chose to ignore its own intelligence and under the War Measures Act a number of orders and regulations were passed to ensure (as I see it) that the Japanese Canadians would not return to the coast.

So when the news of our eviction came we were shocked. We had grown up with so many friends and neighbours and suddenly reality set in that we were to be banished. Our grandparents had been living in Cumberland since 1891 and all their children (except one) were born there.

Most adult males were working in coalmines and suffered the same fate as others in mine explosions. Some were killed in logging. A few ventured in businesses where others may not.

There was no racial barrier when it came to playing baseball. Everybody loved the sport and was either a player or a fan. No one was left out.

We lived and played just like other kids, playing hopscotch, skipping rope, jacks, kick-the-can, swaying on treetops, and sometimes in the evening swatting bats with a broom. We also took part in Maypole dances.

We had many good friends but too many to name here, except Florence Bell (Clark). Florence’s Uncle Ralph lived in Nelson.

But our normal life suddenly came to a halt. Officials came and took away our radio, camera and guns (in our case, a 12-gauge shotgun and a 30-30 calibre Savage rifle). All windows had to be blinded and, of course, our movements were controlled by curfew.

When the officials were about to leave I came out of the other room with a toy pistol. Instinctively, I hid the gun behind my back. The police noticed and asked what I had and Mom told them it was a toy gun. They didn’t believe her and I had to show them my gun – two pieces of stick nailed together.

One incident I recall is someone seeing a human figure sitting outside in the dark and the adults saying that he was a spy. I remember peeking out the window through a slit in the shade and saw for myself the image of a man with a hat on sitting on a step by the shed in front of our house.

I also saw the glow from the cigarette that he was smoking. Some of the adults went out to confront him but he fled towards the sawmill and disappeared.

I also remember quite clearly my parents discussing what to do with the four or five crocks of various sizes that were kept inside a shed. I heard them saying that they were coming back so to leave them there.

As it turned out, the British Columbia Security Commission had no intention of safe guarding our properties for they were vandalized and homes, autos, trucks, fishing boats, farms and businesses, representing the owners entire life-savings, were sold without the owner’s knowledge or consent and at a fraction of their value.

I personally saw on file at an archive a property owned by a Japanese in North Vancouver sold to a neighbor within weeks of his departure. The Vancouver city council merely rubber-stamped the applicant’s request to buy the neighbour’s property, at his price.

Houses weren’t the only victims to vandalism. The Japanese cemetery was also desecrated. When I first visited the cemetery in Cumberland I found the scene absolutely disgusting. I thought to myself, “What kind of people would do such a thing?’ Granite headstones and wooden posts were smashed and scattered all over. I noticed that the adjacent Chinese cemetery had also suffered some destruction at one corner. The perpetrators probably mistook it to be Japanese before they realized the difference.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police, military and government officials quickly rounded us up. Most Japanese Canadians were living in the Lower Mainland but there were also many loggers, miners, fishermen, farmers and business owners who had made their homes in places like Prince Rupert, Queen Charlotte Islands, Ocean Falls, Rivers Inlet, Powell River, Woodfibre, all over Vancouver Island and on many of the smaller islands on the Straits. Some loggers were even living in cabins north of Mission and up Harrison Lake.

Male adults were shipped to road camps, some families to sugar beet farms in the prairies and still others to self-supporting centers in the interior of the province. Those who voiced objection to separating from their families were sent to the prisoner-of-war camps in Ontario.

The irony of all this was that we were supposed to be enemies and couldn’t be trusted, yet we were building highways, working on sugar beet farms, building our own shelter in internment camps and cutting firewood for the ‘wood-hungry’ factories and homes at the coast.

We were even buying war bonds and I could remember saving aluminum foils on cigarette packages and candy wrappers to help the war cause.

We were given very little time to pack and leave; some only got as little as one and a half hours. There was very little time to properly wind up our businesses and certainly none to see and give a parting farewell to friends. Consequently many of our Caucasian friends (to this day) said that they didn’t know what had happened to us.

With no inkling as to where we were going, we packed only the bare necessities, to stay within the prescribed weight limits, believing that all would be secure and that we would soon return.

But the climate in the Interior was totally different to the coast. We were not prepared for the harsh Rocky Mountain winters and the extreme hot and windy conditions of the Prairies. Consequently, without suitable clothing and adequate shelter, we had to endure added hardship.

The only thing I remember of our boat trip from Union Bay through the Strait of Georgia was walking down a narrow stairway into the crowded hull and almost immediately when the ship started moving, I got sick. I laid down on my side with knees up in a fetal position to stop from throwing up.

I was getting sicker and sicker by the second with cold sweat covering my body. I was rushed up to the main deck and the cool breeze felt so refreshing that I was oblivious to anything but the wish to immerse myself in the cold ocean water.

I clung to the railing and threw up. Relieved, I laid on my side and fell asleep.

My memory was a total blank for several days. I cannot recall anything of our debarking at the Canadian Pacific Railway pier or how we got to Hastings Park Detention Centre.

*This article was originally published by the Nelson Star on April 28, 2017.

© 2017 George Doi