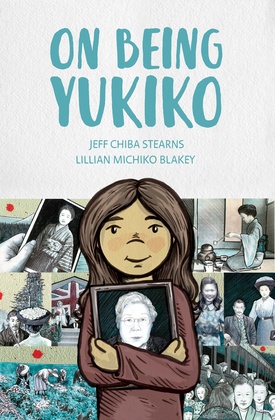

In many ways, On Being Yukiko, a new graphic novel by Lillian Michiko Blakey (Newmarket, Ontario) and Jeff Chiba Stearns (Vancouver, BC) is a book for these Covid-19 times.

As so many of us are trying to define and redefine ourselves, there is a scramble for meaning of any sort during these times. In a time of Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, 18 Million Rising, the spectre of Donald Trump, there is a clear clarion call challenging people to take a stand, to define themselves as individuals and communities.

On a grassroots level, Sansei artist and retired teacher, Blakey, who participated in the On Being Japanese Canadian: reflections on a broken world exhibition at Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum (2019) has been telling her family’s Japanese Canadian internment story at schools in the greater Toronto area for several years. She was born in Alberta and now calls Newmarket, Ontario, home.

Yonsei Stearns has explored his identity extensively through film, most notably, the Emmy-nominated One Big Hapa Family (2010) and most recently Mixed Match (2016). He lives in Vancouver, BC with his family.

Through the magical imaginings of these two talented Japanese Canadian artists, a magical melding of storytelling occurred here as 12-year-old Emma’s story unfolds as she learns about her Japanese roots through the true story of her great-great grandmother, Maki, a Japanese picture bride who journeyed to Canada at the turn of the 20th century. This is a story that many of us have never heard before and one that contains valuable life lessons on what the Issei and Nisei generations sacrificed and suffered to become Canadian. It’s a story that transcends ethnicity and generations, containing life lessons about the complex JC experience that should be read, understood, and inform the evolving world view of school children everywhere who are in fact the key to making sure that we emerge from Covid-19 with a more enlightened understanding of what a new world needs to become.

* * * * *

By way of an introduction, can you please introduce yourselves and talk a bit about how the two of you first got connected?

Lillian: I am a Sansei artist and writer. Three years ago, I created a picture book, The Picture Bride, about my grandmother’s life. I thought that an animated version would reach a new audience of young people. Jeff Chiba Stearns’ animated films excited me so I sent a proposal to Jeff and he replied immediately. But as time passed, I thought that the story needed to include Jeff’s story. I didn’t want it to be a story only about the past. I suggested a graphic novel which would feature an intergenerational story between a grandmother and her granddaughter. Jeff was really excited. He skillfully merged our two very different artistic styles into a book which is appealing to both adults and children. We have never met face-to-face. Jeff is in B.C. and I live in Ontario.

Jeff: I am an Emmy-nominated, Webby award-winning animation and documentary filmmaker, author, and illustrator. I founded Vancouver-based Meditating Bunny Studio Inc. in 2001. My short and feature length films, including What Are You Anyways? (2005), Yellow Sticky Notes (2007), One Big Hapa Family (2010) and Mixed Match (2016), have been screened around the world in international film festivals, garnering dozens of awards.

Being Yonsei, with mixed Japanese and European roots, my work often deals with multi-ethnic identity. I coined the term ‘Hapanimation’ to describe my style of blending anime and manga with a North American cartoon aesthetic. After having two children, I turned my focus away from filmmaking and towards creating children’s books. In 2018, I wrote and illustrated my first picture book Mixed Critters, and Nori and His Delicious Dreams (2020), my second children’s book. I had a great time collaborating with Lillian on On Being Yukiko, which for both of us, will be our first graphic novel.

Can each of you describe what it was like doing this book during this time of Covid-19?

Lillian: Working on this book with Jeff has given me a huge purpose of doing something unique and meaningful during Covid-19. Being isolated gave us the opportunity and time to focus entirely on the book.

Jeff: Covid-19 shut down a lot of my promotion for my most recent children’s book, Nori and His Delicious Dreams. I had to cancel engagements. Being in lockdown meant that it was a good time to start a new project. Because of Covid-19, Lillian and I were able to get On Being Yukiko finished in record time. We started the project around the end of April 2020 and goes to print at the end of October 2020. Basically, we completed the book in six months!

With the Black Lives Matter protests happening, the kids in the book make references to racial profiling and white privilege, which have become common items in the news and at home. We felt that this book could help further the dialogue on anti-racism movements during this critical time.

As artists, what are the commonalities that you share? Were there any JC generational considerations that you had to reconcile? What does being Japanese Canadian mean to you?

Lillian: We did not write the book for personal financial gain. We wanted children to remember the injustice to Japanese Canadians in the past to ensure that the Canadian government will never take away the rights of its own citizens again. We wanted to produce a book which addresses many layers of concerns for diverse mixed-race families.

Jeff: Ever since I was a teenager, I’ve wanted to create comic books. Lately, I noticed how popular graphic novels were with my friend’s kids. When Lillian suggested a collaborative graphic novel, I agreed that this would be a great story for youth and pre-teens.

Lillian had already created illustrations of her family history. Therefore, I could focus solely on the present storyline between the grandma and her granddaughter, Emma Yukiko. The historical story is true; the present-day story is fictitious. Like the intergenerational story in the book, this is truly an intergenerational collaboration between Lillian and myself.

Can you talk a bit about your own family’s internment experience?

Lillian: When Japanese Canadians were removed from the West Coast, my grandmother refused to have the family split up, so my mother’s family chose to go to hard labour in the sugar beet farms in Alberta. My father was engaged to my mother in Vancouver, but being a single man, he was sent to a road camp at Griffin Lake. In 1944, he was finally given permission to leave the camp and marry my mom in Alberta. My sister and I were born in Alberta.

In 1946, my aunt and her family relocated to Japan. My grandparents followed in 1947. My parents chose to stay in Canada. Mom and Dad worked the sugar beet fields until 1952 when we came to Toronto. I have moved 29 times and finally live in Newmarket, Ontario, just north of Toronto.

Jeff: My family was one of the few Japanese Canadians who weren’t interned during WWII because they were living outside of the British Columbia West Coast 100-mile zone. They lived in the interior of British Columbia, in Kelowna where I was born and raised. While they did experience intense racism during the war, they were allowed to stay in Kelowna and keep their house.

Culturally speaking, how difficult/or not is it to understand your parents’ and grandparents’ generations?

Lillian: My parents never spoke of the wartime injustice. In 1995, when I asked my mother to write down her story for her grandchildren, I understood for the first time, her horrific experiences.

When I was six, I had stopped speaking Japanese. My grandmother returned from Japan in 1962 and stayed with us for six months, but I could not communicate with her. She understood English but could not speak it. I could understand Japanese but could not speak it. Today I regret the loss.

Jeff: I wish that I had the opportunity to speak Japanese. My grandparents spoke Japanese to each other but never to us… unless they were angry with us grandkids. Then we’d hear a lot of Japanese swear words. My mother and her sisters who are Sansei never learned Japanese either. My grandparents never taught Japanese to them so that they could better assimilate as Canadians. Kelowna, at the time, was a very white city and after the war there was still a lot of racism towards the Japanese.

© 2020 Norm Ibuki