WOODLAND, Wash. — Morning sunlight spilled into the garage, illuminating a bent figure, about 5-foot-2. George Tsugawa was plucking weeds from potted plants. At 99, he still helps with the family-run nursery.

Tsugawa Nursery, minutes from his home, is a marvel of floral carpets, Japanese maples and fairy-like bonsai forests, drawing garden enthusiasts from across the Northwest.

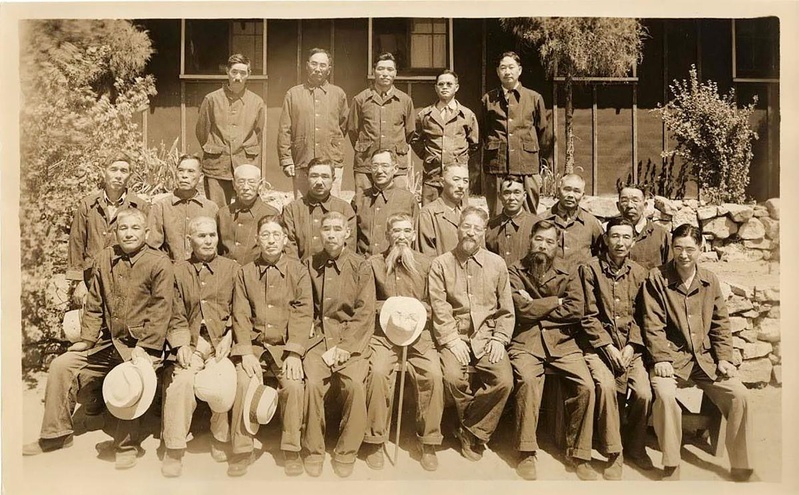

But in addition to its inviting, multicolored beauty, the nursery holds a story of hardship and hope during wartime. Its founders, George and his late wife Mable, were both Japanese-American prison camp survivors.

Seventy-five years ago this week — Sept. 2, 1945 — Japan formally surrendered, ending World War II. In the months following, thousands of Japanese-Americans, including the Tsugawa family, were released from prison camps that had isolated them.

After the Japanese military bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, resentment and fear festered toward people of Japanese descent. Even those born in the U.S. as late as February 1942 were included in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Executive Order No. 9066, which led to all Japanese-Americans on the West Coast — 120,000 people — to be put in prison camps, euphemistically called “internment” centers. Most were U.S. citizens.

High school students have learned about this chapter of World War II in history class. The lesser-known story is how the Japanese-American community intersected with agriculture, to the benefit of both.

Before the war, two-thirds of West Coast Japanese-Americans worked in agriculture or related sectors, according to the University of California-Berkeley. In the camps, many continued to farm and garden. And postwar, though most survivors had lost their land, many returned to agriculture, leaving a lasting mark on the nation’s food, floral and landscaping industries.

Farming behind barbed wire

“I remember when they came for us,” said George Tsugawa.

Tsugawa was 20. His dad had died six years earlier, and his mom, a single parent with stage four cancer and seven kids, ran a fruit stand in Hillsboro, Ore.

The Tsugawas were told to abandon their home and business.

“They said we’d get everything back,” said Tsugawa.

They didn’t.

He recalls his family was bused to the Portland Assembly Center, a temporary detention camp and former livestock facility. The Tsugawas slept in a livestock corral that smelled of urine and manure with no ceiling and a canvas flap for a door.

Later, Tsugawa recalls, they were herded onto a train — shutters down, destination unknown.

They arrived at the Minidoka War Relocation Center near Twin Falls, Idaho. According to Densho, a history nonprofit, the camp swelled with 7,318 Japanese-Americans.

They lived in structures resembling Army barracks. A wall with armed guard towers traced the perimeter of the camp. The earth, Tsugawa recalls, grew mainly sagebrush.

Each of the nation’s 10 camps had working farms where internees grew food for self-sufficiency. According to Central Washington University, administrators also shipped food surpluses to other centers, sold them on the open market or contributed them to the war effort.

It was a time of food shortages.

“If they didn’t want a food shortage, they should’ve thought about that before they locked up some of the country’s best farmers,” said Bonnie Clark, an archaeologist at the University of Denver who studies the incarceration camps.

Agriculture in the camps was no accident. Some War Relocation Authority administrators came from the Department of Agriculture, according to Harvard University Press. Officials chose some camp locations to test their agricultural potential.

Some internees were given passes to temporarily leave camp to work on Idaho farms with labor shortages. Tsugawa received a pass, and spent months hauling sugar beets.

Between 1942 and 1944, about 33,000 Japanese-Americans were put to work on farms, according to the Pacific Northwest Quarterly.

Japanese-Americans were paid for their work, but not much. At Tule Lake Relocation Center in California, more than 1,000 Japanese-Americans did field work, most earning $12 a month, a quarter of what farmworkers typically earned at the time, according to Portland State University.

Dana Ogo Shew, oral historian at Sonoma State University, said Japanese-Americans were used to farming poor-quality soil.

“As immigrants facing discrimination, they weren’t given access to land thought of as best quality,” said Shew.

The California Alien Land Law of 1913 and similar laws in other Western states barred Isei — first generation Japanese immigrants — from owning land. Despite this, by 1940, Nisei — their American-born children — bought land, and the families grew nearly 40% of California’s vegetables.

They made good use of bad soil.

Japanese-Americans are credited in the Journal of Arizona History as the first Arizona farmers to ship cantaloupe, strawberries and lettuce out of state. Today, thanks in part to their innovations, Arizona ranks second to California in lettuce production.

While George Tsugawa farmed, many of his friends at Minidoka volunteered to join the U.S. Army to fight on the European front.

“That was probably the saddest moment of my life. The boys wanted to prove to the world they weren’t traitors. Their parents were begging: ‘Don’t go. You don’t owe them nothing.’ But my friends went. Many of them never came back,” he said.

Tsugawa squeezed shut his eyes, his lashes wet with tears.

In 1944, because Tsugawa’s mom was dying of cancer, authorities released his family. A local man named Reverend Andrews took them in.

“I’ll never forget his kindness,” said Tsugawa.

Generosity of spirit

Tsugawa was not alone experiencing kindness during WWII.

Janice Munemitsu, 63, a California farmer turned ministry leader, recalls how kindness shown to her family during incarceration shaped American history.

Munemitsu’s immigrant grandparents and their children — Janice’s father, uncle and aunts — grew strawberries, beans, squash, tomatoes and asparagus in Westminster, Orange County.

In May 1942, officials decided to relocate the Munemitsus.

But a neighboring family, the Mendezes, saved the farm by leasing it from the Munemitsus while they were incarcerated. Felicitas Mendez was from Puerto Rico; her husband, Gonzalo, was from Mexico.

“It was this idea of immigrants helping immigrants, neighbors helping neighbors. My family didn’t even know them very well,” said Munemitsu.

It wasn’t until years later that both families recognized the simple act of kindness impacted the American civil rights movement.

In the 1940s, there were only two schools in Westminster: one for whites, one for Hispanics. Because all-white 17th Street Elementary provided a better education, Felicitas and Gonzalo Mendez wanted to enroll their children and nephews there.

When their daughter, Sylvia, turned eight, they tried to enroll her — but she was denied on the basis of her skin color and Hispanic surname.

Sylvia’s parents would not take no for an answer.

Felicitas worked the farm, giving Gonzalo time to take the Westminster School District of Orange County to court.

The lawsuit lasted years and ended at the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco, where the judge ruled segregation violated the 14th Amendment.

The Mendez children at last enrolled at 17th Street Elementary.

Although the decision only applied to a handful of California schools, legal historians say Mendez v. Westminster set a crucial precedent for ending segregation. Thurgood Marshall, later appointed to the Supreme Court, had filed an amicus brief in the Mendez case. In it he included the arguments he would later use in Brown v. Board of Education, in which the Supreme Court ruled racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.

The Mendez case also influenced then-California Gov. Earl Warren. Eight years later, when Marshall argued Brown before the U.S. Supreme Court, Warren was chief justice.

The Mendez family says their case, a landmark in the civil rights movement, likely never would have been possible without the Munemitsu farm, because in the early years, they funded the lawsuit almost exclusively with farm income.

When the Munemitsus were released from incarceration, the two families lived together a summer, harvesting the crops and splitting profits. The Mendezes then returned the land to the Munemitsus.

Most Japanese-Americans were less fortunate. Historians estimate, with lost businesses, farms and homes, incarceration cost Japanese-Americans about $4 billion in today’s values. By 1960, the number of Japanese-American farmers had dropped to a quarter of their prewar numbers.

“We were fortunate. The Mendez family showed mine generosity of spirit,” said Munemitsu.

Gardens in the desert

Beauty in a time of despair arose from an unexpected place, too — within the camps.

Tommy Dyo, now 57, recalls as a kid asking his parents about their incarceration experiences. Now, surrounded by letters and photographs, he tells their story.

Tommy’s grandfather, Tsutomu Dyo, immigrated from Japan to Mexico in 1906. The son of a concubine, he had no rights as an heir in Japan and had set out to make his fortune.

Dyo rose to wealth as a silver miner in Chihuahua, Mexico, but lost his fortune through political events. He moved to the U.S., married a woman named Masayo and became a California tomato farmer.

During World War II, the Dyos and their children were uprooted from their farm.

Ken Dyo, Tommy’s father, was then a student at Santa Barbara College. He managed to finish his botany degree before being spirited off to Arizona’s Gila River Relocation Camp.

Ken shared a love for botany with many internees. In the desert, Japanese-Americans grew lush gardens.

Clark, the archaeologist, has also found evidence of hundreds of gardens at Amache Relocation Center in Colorado.

When the Japanese-Americans were relocated, she said, many brought seeds, tree saplings and tools.

Clark has also discovered objects they made: watering buckets from tin cans with little wire handles, concrete-chunk walkways, compost from egg shells, coffee grounds and fish meal.

Access to water was limited at Amache, said Clark: one spigot served 200 people. That they shared so well, Clark says, is “evidence of cooperation.”

It wasn’t just at Amache. At every camp, there were beautiful gardens and even parks.

One of the largest parks was at Minidoka, where Tsugawa lived. Merritt Park at Manzanar, in California, the largest of all, had a waterfall, ponds, a tea house and flower gardens.

“In a sense, what they did was the best medicine. Japanese philosophy says nature is something you honor. And I think there’s something about that connection to the land that in times of uncertainty is very reassuring,” said Clark.

Not every internee found solace. Tommy said his grandfather died a “drunk and bitter man.” But his father, Ken Dyo, went on to become a renowned certified landscape architect.

Postwar, historians say many Japanese-Americans started gardening and landscaping businesses that transformed industries — and Americans’ lawns — for decades to come.

Out of the dust

Japanese-Americans also transformed the nation’s floral and nursery industries.

Shew, the oral historian, said the floral industry was pioneered in the 1880s by a pair called the Domoto brothers, who were perhaps the first Japanese to own land in the U.S. and are credited with producing the first commercially grown camellias, wisterias, azaleas and lily bulbs in Northern California — all imported from Japan.

According to Gary Kawaguchi, author of the book “Living with Flowers,” Japanese-Americans were also the first to commercially grow chrysanthemums.

“The nursery and flower industry existed before the Japanese were here. But once they got into it, they dominated it and took it to a level it had not seen before,” said Shew.

George Tsugawa, the nursery founder, recalls he met Mable Taniguchi in 1949, married her in 1950, and moved to Woodland in 1957 where the couple raised six children and started a berry farm with George’s brothers.

The farm was a success. But when Mount St. Helens erupted in 1980, volcanic ash ruined the strawberry crop. So the couple founded a nursery; it was Mable’s idea.

The early years were hard. One day, Mable sold nothing but one geranium for $1.25.

“One little flower,” said Tsugawa.

He laughed, his whole face crinkling.

“She didn’t give up. I’ve never seen anybody work so hard.”

Today, Brian Tsugawa, George’s son, is general manager of Tsugawa Nursery; other family members help.

The nursery — like the internment camps — carries stories of courage and kindness.

“I’ve learned a lot in my research,” said Clark, the archaeologist. “I’ve been inspired by neighbors helping each other. And I think the lesson I’ve really taken away is that when people are trying to take your humanity away from you, there’s this beauty in acting humane. You don’t just curse the dust. You take nothing and make it into something of beauty.”

*This article was originally published by Captial Press on September 3, 2020.

© 2020 Sierra Dawn McClain