6. Takahashi and Josephine Conger Kaneko

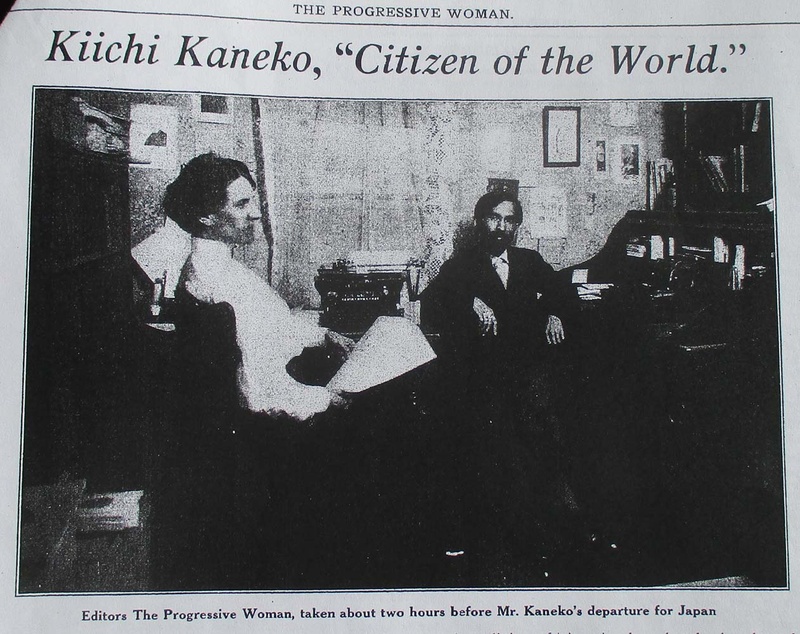

As a member of the IWW, Takahashi also had contacts with the Socialist Party, plus he spent time with known socialist, Kiichi Kaneko. Takahashi visited Kaneko with his friend, Maedako and his cousin, Shizuo Tatsuno, the younger brother of Fumio Tatsuno. Shizuo arrived in Chicago in fall 1906 and worked at Shichiro Yamada’s tea store with Takahashi. Kaneko and his wife, Josephine, began publishing a feminist magazine entitled, The Socialist Woman, in June 1907. Takahashi helped them from New York by donating several times to the magazine’s circulation fund.1

Kiichi Kaneko returned to Japan and died there in October 1909. It was at this point that Takahashi sympathized even more with his widow, and helped her to continue publishing her magazine by translating Japanese newspaper articles and giving her information on the labor movement in Japan.2 During the week of May 1-6, 1910, the fifth convention of the Industrial Workers of the World was held in Chicago and delegates came “from all important places” in the country.3 Did Takahashi attend the convention as a delegate from Japan?

Meanwhile, back in Japan, from May to October 1910, the Japanese government arrested twenty-six socialists and anarchists under suspicion of conspiracy to assassinate the Emperor. Denjiro Kotoku and Suga Kanno, his girlfriend (Kotoku had divorced his wife, Chiyo, in March 1909 due to political differences,) were among those arrested.4 News of the arrests quickly spread overseas through Reuter’s news dispatches and Sen Katayama’s “Protest to the International Socialist Bureau and to the Radical Press of the Western World,” throughout September 1910.5 Additionally, Katayama wrote an article for the August 1910 International Socialist Review to protest the harsh persecution in Japan. He also wrote a letter and sent it to Jean Longuet, editor of the French socialist daily, Humanite.6 Katayama’s appeals to the world called for criticism of the Japanese government, were directed not only to America but to Europe as well.

The biggest protests in the U.S. were in New York and San Francisco. Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, editor of Mother Earth, “with the help of Leonard D. Abbot, president of the Free Speech League, initiated a protest...holding private and public meetings, bombarding the press, and otherwise working strenuously to arouse public opinion” in New York. In response to the arrests of the Japanese socialists, poet/critic Sadakichi Hartmann, who was of half-Japanese, half German descent, wrote a powerful manifesto that was widely distributed on behalf of the condemned (Japanese) comrades.7

Even famed author Jack London supported a protest that was organized by Japanese socialists in the San Francisco Bay Area.8 In a letter to the Japanese ambassador to the United States, dated November 24, 1910 and published in the Oakland Enquirer on December 10, 1910, London wrote: “As a lover of liberty and a citizen of the world I do most earnestly protest to you…. I sign myself one of the great army of international soldiers of freedom.”9 Emma Goldman asked that readers of Mother Earth “not fail to send, immediately, an urgent protest to the Japanese ambassador, at Washington D.C.”10 Josephine Conger Kaneko followed Goldman and wrote in her recently renamed magazine, The Progressive Woman, that she“hopes that its readers will send to the Japanese ambassador at Washington a protest against such barbarous proceeding. Let us see that Japan does not follow in the footsteps of its savage brother Russia, in the persecution of Liberals.”11

In Japan, the court procedures concluded in December, 1910 and death sentences were given to twenty-four prisoners in mid-January 1911. In response, a large international protest meeting was held in Chicago in December 1910.12 According to The Chicago Daily Socialist, published on January 19, 1911, “the National Executive Committee of the Socialist party, at its last meeting in Chicago, issued resolutions to all the locals in the United States to the effect that protest meetings be held to denounce the arbitrary and tyrannical action of the Japanese government” and that “A similar resolution for protest meetings [also be] sent by National Secretary Barnes to Camille Huyamans, secretary of the International Socialist party.”13 Huyamans immediately replied that “a great European movement has been organized…If you read European papers you will see meetings took place in nearly all great towns.”14 Condemning Japan, Barnes said that “(Japan) has written herself backward several centuries toward barbarism…Gross cowardice is the unfailing evidence of abject fear.”15

In the midst of the growing criticism of Japan, the Chicago Evening Post alsopublished an article, titled “Japan and her Anarchists” on January 19, 1911, which included the following:

No one shall be deprived of life and liberty without a fair and open trial. It is to be regretted, therefore, that the present administration in Japan, should have failed to conserve the constitution upon he only occasion in recent years… This is the sort of occasion upon which the Anglo-Saxon takes a secret pleasure in his Bill of Rights. …Japan can scarcely be said to have a constitutional government when no man there dares to raise his voice in behalf of the constitution.

Feeling the urgency to respond to this criticism, Keiichi Yamazaki, Consul of Japan, immediately issued the following refutation:

“The principal criticism seems to be on the ‘secrecy’ of the proceedings. Article 59 of the Japanese constitution provides that ‘trials and judgments of a court shall be conducted publicly. When, however, there exists any fear that such publicity may be prejudicial to peace or order, or to the maintenance of public morality, the public trial may be suspended by provision of law or by the decision of the Court of Law.’ Anyone who appreciates the spirit of Japanese loyalty, which will never tolerate such an ominous plot against the throne as the present one, will understand why a public trial would have affected peace and order. …Japan is not in the least against socialism. Anarchy, however, is suppressed there as elsewhere in the world.”16

Disregarding the few hundred letters of protest received by Japanese consulates in New York, San Francisco and Vancouver,17 as well as the numerous protests and demonstrations in New York and San Francisco, the Japanese government hanged twelve Japanese male radicals, including Kotoku, on January 24, 1911 and one female activist, Suga Kanno, on January 25, 1911. Kanno left these words for her English teacher in San Francisco: “I have lived for liberty and will die for liberty, for liberty is my life.”18

Hiroichiro Maedako showed Takahashi the newspaper article which reported the execution of Kotoku in Japan. After reading the article, Takahashi simply yelled, “Damn it!” and fell into silence.19 In New York, a large and enthusiastic mass meeting “to pay tribute to the memory of our martyrs” was held on January 29, 1911,20 in response to a call by the Kotoku Protest Conference, which represented various radical and labor organizations. A spontaneous manifestation of indignation and sorrow, in the form of a street demonstration, followed.21 While marching to the Japanese consulate, three demonstrators were arrested. Big protests were held in San Francisco as well. But surprisingly, there were no reported protests in Chicago: the Chicago Tribune simply reported “12 Anarchists Hanged in Tokio”22 and “New York Anarchists Riot.”23 Consul Yamazaki in Chicago reported to Tokyo that people in Chicago were basically indifferent about the issue.24 Later, Emma Goldman also admitted that “my greatest regret regarding Chicago is that I failed to interest our friends in the Kotoku Memorial. There was a lack of speakers; besides Japan is far away; even Anarchists do not easily overcome distance.”25

Would Takahashi have participated and voiced his sorrow and anger at a meeting of the Kotoku Memorial in Chicago had there been one? We know that Takahashi did donate 50 cents to the Kotoku Defence Committee Fund that Goldman and Berkman established in New York to help those arrested in the protest demonstrations.26 After Kotoku’s death, Takahashi lived humbly in the attic of Yamada’s home, helped with deliveries three days a week, and started studying at Northwestern University.27 Giving himself the English name of Charles T. Takahashi, he also joined the Cosmopolitan Club at Northwestern University.28

Josephine Conger Kaneko published a special edition of The Progressive Woman, featuring Denjiro Kotoku, in May 1911. Takahashi and Shizuo Tatsuno were contributors; they gave her suggestions and helped her publish it. Takahashi also translated nineteen letters from Denjiro Kotoku and Toshihiko Sakai, a comrade in Japan, to Kiichi Kanako, into English. The letters dated from 1904, when Kaneko was still on the east coast, to 1907, when Kotoku’s newspaper, Heimin Shimbun, was banned in Japan.

Tatsuno also wrote a long article entitled, “Japan’s Twelve Noblest Souls,” and praised Kotoku as follows: “His life through and through was that of a warrior’s, of a brave soldier of the humanitarian movement” and finished his article with this description of Kotoku: “with a sublime smile on his face, …with his twelve followers he shouted, “Ban Zai!”29 While protests against Kotoku’s execution calmed down after a while in the U.S., the Japanese government continued confiscating all papers and magazines on the subject of socialism or anarchism30 and the conditions for the socialist movement in Japan steadily grew more unbearable.31 After Kotoku was removed from the scene, the movement entered into a period of “winter.”

7. Takahashi’s Last Years

Maedako’s writings include an account of Takahashi’s naïve affair of the heart in Chicago. According to Maedako, Takahashi had crush on a young American woman named Clara, who he met at Josephine Kaneko’s house.32 Clara was a college student who volunteered as a typist in the office of the Woman’s National Committee of the Socialist Party because she was bored with student life. Josephine Kaneko had given up her independent publishing business and adopted co-editorship with the Woman’s National Committee of the Socialist Party. In August 1912, Josephine published her magazine in their office at 111 North Market Street.33 Takahashi must have met Clara around this time. Clara helped Takahashi write and practice his English speeches and went to meetings with him.34

Although the beauty of youthful unrequited love had finally come to his poverty-ridden daily life, tuberculosis was gradually having serious effects on Takahashi’s health. Hoping for better chances of recovery, Takahashi chose to leave Chicago to live in Southern California. Maedako saw him off on the night of his departure. It was a snowy evening, and, according to Maedako, Takahashi got into an automobile for the first time in his life, headed for the train station, and disappeared into the snow.35 It was the last time Maedako ever saw Takahashi.

After a few months, Maedako received a short letter from Takahashi. Takahashi wrote that he planned to work on a fruit farm through the summer, recover in the fall, and then to go back to Japan. His address was on San Rio Drive, near Los Angeles, andhe said that he lived in a tent on a mountain, one mile from that address.36

Maedako did not hear from him for about a year, so he made inquiries about Takahashi with the Japanese Association in Los Angeles. According to their reply, which Maedako described in his story, Seishun no Jigazo, Takahashi had become a shepherd for a man named Mizoguchi in Los Angeles. He was always quiet and did not communicate much with others, and appeared to enjoy being alone. But one day he felt sick and stayed in bed for about three days. On the fourth day, bored with staying in bed, he forced himself to go up the mountain. He did not come back that night, and the next day he was found dead in his tent. The cause of death was hemoptysis (coughing up blood) and since he was found dead on the road, the Japanese Association buried him in the Japanese cemetery.37

About ten years after Takahashi left, Tetsugoro Takeuchi arrived in Chicago. Since he was an anarchist member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, Takeuchi had been watched for twenty years by the Japanese government. It was known that he had lived as a student in San Francisco around 1903.38 He may have had contact with Takahashi, when they were both filled with the energy and dreams of their youth. Takeuchi moved to Chicago around 1925, after living as a vagrant and working as a domestic at 53 W Chicago Avenue. In 1931, Yoshio Muto, the Japanese consul, reported to the Japanese government that Takeuchi had not made any contacts with Japanese residents in Chicago and that he no longer seemed to be involved in any radical movements.39 It is unknown how long Takeuchi stayed in Chicago, but he briefly returned to Japan in 1939, then came back to his former haunt, San Francisco, to run a restaurant with his wife, in February 1940.40

Takeshi Takahashi has never been acknowledged in Japanese socialist and anarchist history to the same extent that Denjiro Kotoku or Kiichi Kaneko has, probably because he was humble, sincere, and genuine—the kind of person who would make small donations to various comrades from his meager income. He may not have been noticed because his appeals were mainly addressed to Japanese immigrants and American comrades, not to the Japanese in Japan, and because he died very young and alone in the U.S. But Takahashi’s internationalism should be treasured and remembered as a good example of Chicago’s potential for “furious growth and bruising social dynamics,”41 a place that was once cherished and embraced by Japanese idealists. The timeless beauty of his life in Chicago can be crystalized in a famous haiku of the renowned poet of 17th century Japan, Matsuo Basho, who wept:

natsukusa ya/tsuwamono domo ga/yume no ato

(summer grass/the only remains of soldiers’/dreams.)42

Notes:

1. The Socialist Woman January 1908, March 1908.

2. Dai-Bofu-U Jidai, page 126.

3. Mother Earth, July 1910.

4. Yamaizumi, Susumu, ‘Taigyaku Jiken to The Progressive Woman’, Meiji Daigaku Kyoyo Ronshu, page 39.

5. Havel, Hippolyte, ‘The Kotoku Case’, Mother Earth, Dec 1910.

6. Mother Earth, January 1911.

7. Goldman, Emma, Living My Life, page 474.

8. Ohara, Satoshi, ‘Taigyaku Jiken no Kokusai-teki Eikyo’, The Journal of The Tokyo College of Economics, No. 34.

9. The letters of Jack London, Volume Two 1906-1912, page 946.

10. Mother Earth, Dec 1910.

11. The Progressive Woman, December 1910.

12. The Agitator, January 1, 1911.

13. The Chicago Daily Socialist, January 19, 1911.

14. Ibid.

15. The Chicago Daily Socialist, January 20, 1911.

16. The Chicago Evening Post, January 21, 1911.

17. ‘Taigyaku Jiken no Kokusai-teki Eikyo’, The Journal of The Tokyo College of Economics, No. 34.

18. Mother Earth, February 1911.

19. Seishun no Jigazo, page 115.

20. Mother Earth, May 1911.

21. Mother Earth, February 1911, May 1911

22. Chicago Daily Tribune, January 25, 1911.

23. Chicago Daily Tribune, January 30, 1911.

24. Consul Yamazaki’s Report to Foreign Minister Komura, January 21, 1911, Taigyaku Jiken Kankei Gaimusho Ofuku Bunsho.

25. Mother Earth, March 1911.

26. Mother Earth, May 1911.

27. Seishun no Jigazo, page 113.

28. 1914 Northwestern University Yearbook.

29. The Progressive Woman, May 1911.

30. Mother Earth, July 1911.

31. Mother Earth, March 1911.

32. Dai-Bofu-U Jidai, page 125.

33. Ibid, page 132.

34. Ibid, page 123 and 165.

35. Nichibei Shuho, December 29, 1917.

36. Ningen (Tairiku-hen), page 416.

37. Seishun no Jigazo, page 183, Nichibei Shuho, December 29, 1917.

38. Shakai-shugi-sha Museifu-shugi-sha Jinbutsu Kenkyu Shiryo 1.

39. Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 1-4-5-2.

40. California, Passenger and Crew Lists 1882-1959.

41. The Encyclopedia of Chicago, page 144.42.

42. Reichhold, Jane, Basho: The Complete Haiku, page 137, 322.

© 2020 Takako Day