“I think that Nikkeis were quite lucky in that sense, because we always worked so hard and our parents always taught us never say or do anything that is troublesome or bothers other people — have good respect for people and manners.”

— Rose Tsunekawa

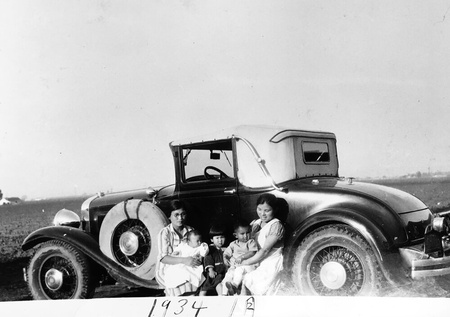

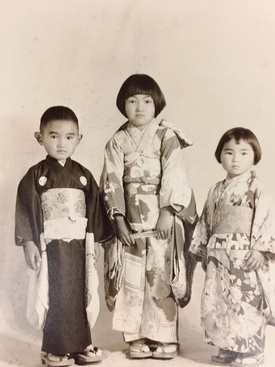

Along California’s Central Coast in the farming town of Salinas, Rose Tsunekawa grew up as the eldest daughter of an Issei father, Yasuichi Ito, and a Kibei mother, Kikuyo Yonemoto Ito. Despite the fact that her father was prohibited from owning land and the Depression years defined her childhood, photos of the Itos in the 1930s show a self-made family that’s happy, stable, and proud. The children are pictured petting the family’s dog, riding on bikes, and wearing kimono, often posed in front of their father’s Dodge — a symbol of his successful harvests.

Had the family stayed in Salinas, they would have met the same fate as their Japanese American neighbors: uprooted and imprisoned in camp. In fact, Rose’s father was already being watched by the FBI for sending care packages to Japan’s Imperial troops in China. (The packages were often filled with seemingly insignificant but rare and thus precious American luxuries — cans of pineapple and Hershey’s Kisses). One year before Pearl Harbor, the Itos left California on one of the last ships to Japan to bring their grandfather home to live out the rest of his years. But in their home of Nagoya, they would experience the terrors of war from the other side of the Pacific; surviving air raids, food shortages, and the devastating defeat of Japan.

In the aftermath of the war, Rose’s bilingual abilities and U.S. citizenship got her jobs working for the U.S. military, and living in Japan would allow her to cross paths with her future husband, Tats Tsunekawa. But before getting married to Rose — who was considered army personnel — Tats had to be approved, and even went so far as to get part of his lung removed to erase traces of his past tuberculosis. They eventually returned to California together, raising a family and retiring in the heart of the Bay Area, not far from where Rose’s parents had first settled, nearly 100 years earlier.

* * * * *

My name is Rose Asako Tsunekawa, used to be Ito. And I was born July 9th, 1930 in Salinas, California.

Can you describe a typical day for you growing up in Salinas?

My grandparents were here first and my grandfather was a carpenter. I don't know how he did it here because he didn't understand any English, or drive or anything. But he came here and so when my father was 16 years old in 1918, he came because his father was here around Salinas.

And I heard that it was very hard living in those days. Most of the immigrants, they were in a barn and on the second floor—or wherever—they had straw and that was their mattress. And then the ladies in those days they had to go work in the fields, too. So there's only one water faucet. The ladies would get up early, like four thirty, five o’clock, so they can be by the water faucet to do their washing before they went to work in the fields. Those were the very hard immigrant days. There was my grandfather, my grandmother, and I was the first born. And we had three Filipino men living in a little place right next to our house.

It was very hard. What prefecture were they from?

From Aichi-ken. And there weren’t too many people from Aichi-ken.There were some families in Stockton, but not around Salinas and Monterey and Watsonville. So whenever the Kenjin-kais had their picnic we were always invited to all of them, which was nice.

So were you living among other Japanese workers?

No. My father every year, he leased a hundred acre lot and we raised lettuce. At one time I think it was sugar beets. But I’m not too familiar with that. I know when he was raising lettuce because we always played in the irrigation ditch [laughs].

So your grandfather migrated, and then sent for his son and wife?

Yes, he was sixteen. And fortunately, unlike the other Isseis that came at that young age, he had his father here. So he was able to go to live with an American family as what they call a houseboy. They would go to school and then they’d come home and they would do a lot of chores for the family. That’s how he was able to learn some English and then after he learned some English, he was able to go to a mechanic school in L.A. So he was one of the fortunate Isseis that spoke some English.

He was one of the first people that was able to get a Caterpillar because I remember my grandfather, he used to plow with a horse. And once the horse went and kicked him and he got a big bulge in his cheek and he stopped doing that. But fortunately my father had bought a Caterpillar. He was a little bit more fortunate. Every year my father had to go sign a lease and he’d go to the landlord’s house. And of course I stayed in the car. And he was never invited in to a white man’s house. The landlord would bring the paper and then my father would hold it against the door outside and sign it. And that was signing the lease for a year. Of course in those days, none of us had telephones.

Now how did your mother come to California?

My mother was born in Hawai’i because her father was a contract laborer or something. They were from Yamaguchi prefecture and my mother was born there. But when she was, I don’t know, a toddler or maybe before grade school, her father decided to go back to Japan. And so she went to Japan and went to grade school there and then later on at 14, 15 years old, she came back to Hawai’i to live with her uncle and aunt. I think my mother’s older sister was living near Salinas and so she, my mother, came from Hawai’i to Salinas and she got married when she was 19. And had to come into a family with a mother-in-law. That was very, I don’t know [laughs].

Was it hard on her?

In those days the mother-in-law, the people that age in their late 40s or 50s, there weren’t that many Issei women that old. And so a lot of Japanese immigrant brides or young brides came to America as a picture bride, most of them. They used to come to our place and talk to my grandmother because she was older and could talk to them.

About life in the United States? Or what were they going to talk to her about?

All these brides I’m sure had language problems, and of course, probably had a lot of issues with their husbands. And they were in a place where they didn’t have any family or anything. So many of them used to come to our place and talk to my grandmother. And in those days, nobody had telephones. So whenever there was an illness or death or something, people were always getting in their cars to let their friends and people know. And I think they had some kind of circulation that they used.

While you were growing up, did your parents speak to you in Japanese?

I was the oldest and so my parents always spoke to us in Japanese. And then we went to Japanese school three days a week after grade school. Our father used to come and they would take turns taking us to Japanese school. And there was a library, about two blocks from there. So, while I waited for the other class to finish, I always went to the library and checked out free books.

So tell me about the family’s decision to go back to Japan. Who wanted to go back and why?

In 1937 Japan started the war with China. In those days of course, the Isseis couldn’t become naturalized, they couldn’t even own homes. My dad every two years, he bought a new Dodge because that was his show of success. He couldn’t buy a house or do anything, but if you worked hard, and his lettuce crop was good, then every two years he bought a new Dodge.

So the war started and of course the Isseis that came here, the men, they were usually called draft dodgers. And also the Japanese word for immigration is imin. There’s another word, kimin. Kimin means to abandon. And so the Japanese people called the Isseis that came here kimin [abandoned people]. And then the men were called draft dodgers. Because at 20 years old, usually, they have to go into the army. And in Japan, in those days, it was the first son that inherited everything, usually the money or the place or assets. But they also inherited the debts, too. But when you are a second or third son, then you have nothing. So those were the ones that came to the United States. You know, it wasn’t a very good time.

So in 1937 when the war started, my dad was 35 years old. And since he was a draft dodger, he formed a club with some of the other Isseis that were at that age. So they used to get together and my mother and grandmother, they used to get the big rice sacks that were in those days, they were I think 50 or 80 pounds, and they were very strong sacks. So they used take that apart and sew them and make care packages. And they used to send care packages to the Japanese troops in China. And Hershey Kisses used to come in a big box, and they would take those boxes apart and then they put a lot of Hershey Kisses. And then they put in pineapple cans. And the Japanese care packages from Japan, they never had anything that nice. I mean, chocolate was out of this world, for, I am sure, everybody. So they sent a lot of care packages to the front lines.

Wow. And your grandmother was part of that?

Oh yeah, my grandmother used to sew, too. We used to gather all these sacks and some of the Issei women after dark would to come to our place and they’d sew and make the care packages. So that’s why they had been sending all these care packages which was very warmly accepted. It was, I guess, such a joy for the troops there.

So my father was the Northern California Vice President or something of this group. They used to call it Heimu shukai, “Association of Men of Army Age,” or military age. [The association’s full name was Heieki gimu shukai, translated to “compulsory military service]. And they used to have this group. And Mr. Yonemoto living in Sunnyvale was the President. And they got invited to go to the front lines in China because they wanted to thank the Japanese, the Nikkeis in the U.S. for sending them such wonderful care packages. And then in 1940 they had this ceremony in Tokyo. Well, I think it’s not true but Japan was saying that their country was started in 2,600 years ago. So in 1940 they were celebrating kigen nisen roppyakunen — that’s 2,600 year. So my dad and Mr. Yonemoto they were invited to that ceremony in Tokyo.

That is so fascinating that your father felt kind of sympathetic to Japan.

Well, in those days, they could not become U.S. citizens.

True.

If they wanted to go to Japan they got a re-entry permit. Not a passport, it’s a re-entry permit. When they came back in 1940 after the ceremony, they had a good trip. The Japanese government, I guess was very appreciative of what they were doing in the United States. And when they came back, my dad and Mr. Yonemoto, they were on the FBI’s blacklist. And my grandmother had passed away in 1939. And my grandfather was quite lonely and he said he wanted to go back to Japan and die. And because things weren’t looking so good for my father, I mean he was still able to farm and everything, but being on the FBI’s blacklist and not being able to do much of anything anymore. So in mid-November, he decided to take us all to Japan. And my grandfather, I think, was happy that he could go back and die in Japan because he was very lonely.

And so we landed in Yokohama around the end of November. It was a 14 day trip. And we didn’t stop in Hawai’i, I don’t know why. I guess things weren’t really that good anymore. Because it happened that our ship was the last ship before the war. Because the the next ship that left San Francisco had to turn back because the war started.

Do you remember the name of your ship, by any chance?

I think it was Tatsuta Maru.

And by this point, did you have siblings?

I had a brother Roy that was two years younger and a sister, Hisako born in 1939. I had another sister, Haruko who passed away in 1937 around the age of three from diphtheria. In those days they didn’t have any medication and she passed away. So my mother in those days was very sad due to Haruko’s death, and then we went back to Japan. She really didn’t want to go back to Japan but she didn’t have much choice.

So we went to Japan and we docked in Yokohama and then a week or two later we went to Aichi-ken near where my father had an aunt. It was in the outskirts of Nagoya. That was in the real countryside. It was mostly farming and so we rented a house. She was widowed at a very young age and she had a small farm, so my father helped with the farming. He was at that time, 39 years old. And my mother was seven years younger than him. So we rented a house, maybe a couple miles from my father’s aunt’s farm. The house was a two-story, very primitive you know. And a Japanese house. And in the back of the house was a grade school, grammar school.

And so when you were in Japan, you were about 12?

I was 11. And the war started December 8th and that was my first day of school in Japan. And so it was Monday and school had started. You know, I went to school, but I didn’t really understand what the teacher was saying. Something about war but I didn’t really understand, my Japanese learning here was third grade Japanese. And because of my age I enrolled in fifth grade in Japan. It was just very hard. In those days, we went to school six and a half days. Saturday was half day. So on Sunday, my brother and I had to go to a private tutor for Japanese. Not just the language. But I had to learn Japanese history and geography.

So when you got home that day, that was Monday December 8th, did your parents tell you what happened?

Oh yeah. They were very, very concerned. And after that almost every day, since we had just come from America, Japanese secret police were after my parents, making sure. Because they wanted to know if we had a shortwave radio for spying or whatever. I think they just stopped by, almost everyday, to make sure, talk to them.

Wow. So on both sides, the FBI in the U.S. and then the Japanese secret police were watching your parents?

Yeah, because we had just returned from the U.S.

And so how did things change, as the war was progressing? How did things change for you in Japan, in school and your friendships?

School was very, very hard. Especially because the military took over everything, you know. So, one of the things I had to learn was how to write in kanji, the 126th emperor’s name. I mean it was things like that we had to learn. I just knew the basic kanjis in third grade. And here I was in fifth grade, third semester, and in sixth grade, you have to study to take a test and to go into girls’ school. And so it was very difficult studying, I think I used to cry all the time. But the schools in America, the Springs School in Salinas, it was more laid back. When I went back to Japan and had to study, I was like a sponge. And I was able to learn fast. The only thing I was good in was arithmetic. Because although I went to Japan in the fifth grade I had known the math for seventh and eighth graders.

This interview was made possible by the Japanese American Museum of San Jose and a grant from the California Civil Liberties Program.

*The article was originally published on Tessaku on October 16, 2019.

© 2019 Emiko Tsuchida