I had the great good fortune to speak to Mrs. Ainsworth’s class at St. Patrick’s Elementary about the 1942 “evacuation” and incarceration, in the Arizona desert, of our Japanese neighbors.

This gave me one more chance to talk about a wonderful family, the Loomises. Sadly, it gave me one more chance to miss my friend, Joseph Ira Loomis, who left us five years ago. I don’t think I will ever get over missing Joe. I don’t think I’m supposed to.

But it was also a wonderful opportunity to talk to young people about important things like honor and character, courage and loyalty, and, most of all, friendship, all of these the qualities that the Loomises and so many other Arroyo Grandeans–the Taylors, the Phelans, the Silveiras, the Bennetts, to name just a few—so exemplified then. They seem in short supply today. But in the World War II years, these were the businessmen and the farm families who shepherded, throughout the desert years, their Japanese neighbors’ fields and homes, their sheds and the expensive irrigation pipe stacked inside, their trucks, and their heavy equipment.

Other, more personal, property–love seats and dining-room sets, rocking chairs and bedsteads, maple dressers and black-lacquered hutches imported from Japan decades before Pearl Harbor–all of these disappeared, stolen or broken up by cowards armed with hatchets.

But others in the Valley outnumbered the cowards. Mr. Wilkinson at his meat market and grocery on Branch Street refused to accept payment when his Issei customers came into his store to settle accounts in April 1942 (“You keep your money. You’re going to need it.”) just before they were shipped to the temporary relocation center at the Tulare County Fairgrounds, where they slept in livestock stalls that stank of shit.

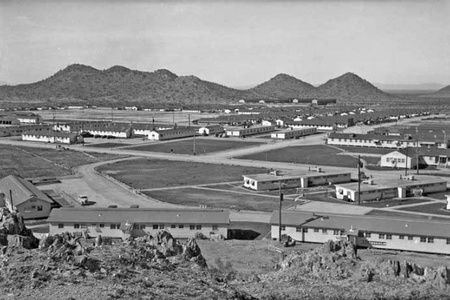

In August, they went to the Gila River camp, where the temperature was at or above 109° for a month, where the winds came up to kill off a generation of grandparents born in Kagoshima or Hiroshima-ken with the spores that carried Valley Fever, where they lived in barracks with cardboard-thin walls that carried them, unwilling, into the deepest secrets of the families on the other side of the wall, where you shook your shoes in the morning for scorpions and let fly balls to left field drop because of the rattlesnakes waiting for you there.

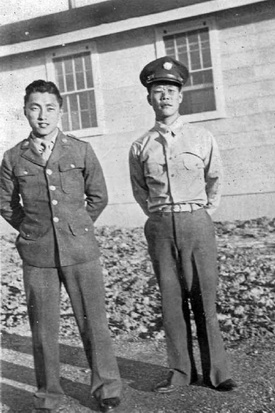

Young people, of course, hated the camps. By 1944, an entire generation was missing from Gila River. The young women got out for jobs or college in Denver or Chicago or St. Louis. The young men got out to college, as well, got out to top sugar beets in Utah or they got out to die in distant Italian mountains or in the forests of the Vosges Mountains in France, where the Germans had learned to fire their superb 88-mm cannon into the treetops to impale the Nisei GIs below with jagged splinters.

In late 1944, the first of our neighbors began to come home.

Ultimately, fewer than half of them would, but a few of those who never lived here again asked their children to bring their ashes home to Arroyo Grande–and this was many, many years after the war–so they could be with their neighbors and their families once more, and forever.

That is what this Valley does to a person. This is home.

In 1945, Mr. Wilkinson, in his meat market and grocery on Branch Street, was just as shameless as he’d been in 1942, and just as generous, in extending credit to the people coming home from the desert alive and hoping for new lives.

The town blacksmith, Mr. Schnyder, repaired the Kobara family’s water pump on Christmas Day 1945 because there are no holidays with crops in the ground. He understood that and he understood, too, the kind of people the Kobaras were—and are.

In the years after the war, the Japanese families who returned to this Valley demonstrated the same qualities that their neighbors had in the days after Pearl Harbor, in gentle but immensely powerful ways.

Sab Ikeda’s 1965 Little League kids were so well-coached that they knew always to take out the lead runner, knew how to lay down a bunt, knew how to grip a curveball. His kids, now in their sixties, still remember all those lessons from Coach. What they remember even more was the constant smile on Coach’s face as he taught them.

When Sab’s brother, Kaz Ikeda, died in 2013—he was a gifted catcher for Vard Loomis’s Arroyo Grande Growers and for Cal Poly (he always said that another brother– I think it was Sei–was the better player), the mourners gathered at the Arroyo Grande Cemetery sang the valedictory hymn: “Take Me out to the Ball Game.” It was, of course, the perfect choice.

When I interviewed Haruo Hayashi, I admired his humor but also his very understated outrage. I was surprised that what upset him wasn’t the incarceration. I suddenly realized what he was telling me in a very soft voice: He trained with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, and he never got over the black GIs standing outside the camp gym for USO shows that the white and Nisei GI’s watched inside. He couldn’t understand something so shameful.

So the families, including the Hayashis, who did come home from the desert not only picked up their lives where they’d left them, but they began, from the moment they came home (despite some of them being denied hotel stays in Santa Maria, some being denied service in local grocery stores), to give their lives to the community that had been stolen from them for three very painful years.

How painful were they? The people who were taken to Gila River refused to talk about the desert with their children, who wanted desperately to hear the stories of what their parents and grandparents had endured. But the Nisei never talked about the desert. Never.

In their public lives, their generosity was open and seemingly effortless. They never stopped giving to their neighbors—in youth sports, in service clubs, in countless volunteer hours, in the Methodist Church, in homes where their refrigerators were always open to a generation of ravenous teenaged boys.

But Gila River remained, both submerged and sharply painful, until they began to approach the ends of their lives.

This is when they began, hesitantly, to open up to historians and to young history students. They began to tell the stories of their lives. Despite the wounds of this terrible war–which included both German shellfire and striking coronary disease rates among those who’d lived in the camps–they decided, in those stories, to give us the most precious gifts of all. In the telling, they gave us honor and character, courage and loyalty, and, most of all, they gave us friendship.

* This article was originally published on the author’s blog on April 13, 2018.

© 2019 Jim Gregory