A wall in George’s home is adorned with three large, framed collages, each one highlighting a milestone race in his career: his first win, his biggest monetary win, and one race that made horse racing history. His very first race took place on March 8, 1954, at Bay Meadows in San Mateo. “I was pretty nervous on that. I tried to hide it but my hands were all wet.” His first mount was Radio Message and he came in a respectable third. Three days later the same track was sloppy; that is, wet and muddy. But it was in those less than perfect conditions that George scored his first win. It was only his third race. He was aboard Sheer Speed and he ran the six furlongs in just over one minute and fourteen seconds. “It was the biggest thrill of my life,” George said.

He returned to the jockeys’ room with his face and silks splattered with mud. All of his fellow riders, Willie Shoemaker, Ray York, Gordon Glisson, Ismael Valenzuela, Joe Philips, and others, went up to him to offer their congratulations with slaps on the back and handshakes. “Johnny Longden came over and said I had ridden a nice race and that made me feel real good.” In fact, George confessed, “I felt like bawling.”

George took the Sport of Kings by storm. Sports page headlines such as “Taniguchi Headed for Greatness” and “Taniguchi New Jockey Sensation” trumpeted his meteoric rise to fame. In his first year his success was compared to that of Willie Shoemaker. One sports writer touted, “George Taniguchi is the hottest piece of talent to hit U.S. tracks since Willy the Shoe.” With 230 wins in his first racing season, George was the only apprentice jockey to rank among the nation’s top five winning jockeys. He was the “winningest” jockey at Bay Meadows in 1954.

He repeated that achievement the following year and added to it the title of top winner at Del Mar, winning as many as five races in a single day. One race track steward attributed his success to “a marvelous sense of pace, a feeling for the right move at the right time.” George concurred, “I think pace is the most important – make sure you have enough horse left.”

His biggest win was the Arlington Futurity in Chicago, six years into his career. The stakes amounted to $218,940, the highest ever seen in the state of Illinois up to that time (1960). “They do that in a week now, but in those days that was huge,” George explained. Mounted on Pappa’s All, George took the lead right out of the starting gate and kept it. He beat out some good horses in that race, including the odds-on favorite from the eminent Calumet Farms.The winner’s purse was $129,000 of which George was entitled to 10 percent.

Without disclosing his annual earnings, George subtly intimated that he did quite well for himself income-wise. Jockeys collected $50 for a win plus 10 percent of the winner’s purse, $35 for placing second, and $25 to show (come in third). The back of the pack received $20 for just riding in the race. Out of their earnings, 20 percent went to their agents for securing their mounts. The jockeys paid a small fee for laundry, and valets were paid for every horse raced. Oftentimes two or three jockeys would share a valet, but others, like Shoemaker, insisted on having their own personal valet to prepare their silks, help them dress, clean their saddles, and shine their boots. The riders also tipped the jockeys’ trainers for rub downs, and dues to the Jockeys’ Guild were deducted from their earnings on a per mount basis. A jockey’s overhead also included his jodhpurs (riding breeches), which ran $22 per pair in George’s day; boots were about $25; and a new racing saddle cost $130. All of the expenses notwithstanding, in a week, George could earn more than he would have working all year as a produce clerk or gardener. But it was easier then, George surmised. “Today, jockeys have to win [consistently] to make it.”

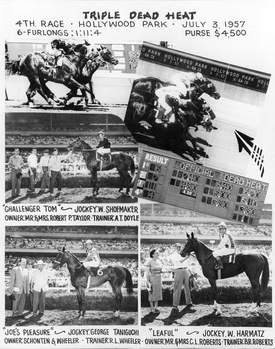

The third collage features a historic race. In horse racing jargon, a “dead heat” is a tie at the wire between two horses and, as rare as it is, tote boards are designed to announce such an occurrence. At the conclusion of the fourth race at Hollywood Park on July 3, 1957, bewildered placing judges poured over photo after photo of the finish. After nearly fifteen minutes elapsed, an eternity in horse racing, the tote board was rigged with a makeshift sign that posted a triple dead heat – a three-way tie! The crowd of 23,489 let out a collective gasp. The three winning jockeys were George Taniguchi, Willie Shoemaker, and Bill Harmatz. It was the first triple dead heat in California and only the third in the history of thoroughbred racing in the United States. As one turf scribe put it, it was one of those days when there were eight races and ten winners.

One race that is conspicuously absent from the framed trio on display in George’s home is his ride in the Kentucky Derby on May 4, 1957. Mrs. Ada Rice asked George to ride her horse, Indian Creek, in the 83rd Run for the Roses. Remembering that first Saturday in May at Churchill Downs, George lamented, “I could have won that race.” But Indian Creek broke down, in other words, suffered a leg injury in the stretch for home. A ruptured suspensory ligament in one of his forelegs forced Indian Creek to drop back and ended up placing sixth in a field of nine. George was, however, the first Nisei to ride in what is arguably the most prestigious race of the sport.

George stands five feet one inch tall, and during his racing days he weighed 104 pounds. With his tack (boots, pants, silks, and saddle), he weighed out at 109 pounds. Other jockeys had to go to great lengths to make weight, “but I was lucky” he said. When getting weighed some jockeys removed their heavy silks and put on crepe paper-like imitations or cardboard boots shellacked to look like shiny leather, and then changed into their regulation gear before the race. The scale clerks were wise to the jockeys’ shenanigans and usually turned a blind eye. The only rule that they enforced without compromise was the saddle the jockeys held when weighing out had to be the same saddle they used in the race. There were no exceptions.

In order to shed pounds jockeys resorted to a wide range of unhealthy, self-inflicted torture. To them it was just part of the job; they called it “reducing.” George once saw a jockey devour a quarter of a watermelon for lunch only to force it back up moments later. It was a matter of routine to walk into the restroom of the jockeys’ quarters and hear the riders gagging in the stalls. “The sound would make me sick,” George commented, “I would shout, ‘Damn you guys!’”

George worried about his weight before a race just once during his entire career. A friend gave him an extremely potent Epsom-based laxative in the form of a little, white pill. “Epsotabs,” George said scornfully, “I’ll never forget that, it just about killed me!” He took only one pill and the outcome was so violent and painful that he vowed never to resort to such measures again. George knew one jockey who casually took four to five Epsotabs a day.

Laura Hillenbrand did not interview George for her book about Seabiscuit because it was not necessary. George’s amazing feat of strength that saved his card-playing buddy Johnny Longden from a likely fatal fall was duly recorded in newspaper articles and racing annals. One headline read, “Taniguchi Saves Longden.” It occurred during the first race at Hollywood Park on July 22, 1955. The announcer shocked the crowd when he blurted out, “Longden is going down between horses! After the race, Longden told a reporter, “I thought I was a goner until Taniguchi grabbed me.” Hillenbrand cited that post-Seabiscuit event in her book to illustrate what she called jockeys’ “extraordinary athleticism.” George downplayed the feat as luck, explaining that both horses happened to be in stride otherwise it would have been out of the question.

George did admit to being really proud of what he did. Not because it displayed his reputed upper body strength, but because of the good sportsmanship it projected. It was an act of chivalry. After all, Longden went on to win the race.

It was at Albany’s Golden Gate Fields in May 1968 that George ran his last race. In the course of fourteen years, he rode in 11,354 races from the West Coast through the Midwest and up and down the eastern seaboard. In 1,597 of those races, George came in first. At the time of his retirement he was ranked among the nation’s leading jockeys based on wins.

On July 10, 1971, George was honored by Hollywood Park with an engraved silver platter for his “contributions to thoroughbred racing during a distinguished riding career.” In presenting the award, James D. Stewart, Hollywood Park executive vice-president and general manager remarked, “We are pleased to pay tribute to George Taniguchi, an outstanding rider and a gentleman who has been a great credit to our sport and our community.” Ironically, the ceremony was held in the Hollywood Turf Club, the very turf club that denied George entry twenty-one years earlier. That was how his journey began – he could not get in to plead his case before an important film producer so he ended up as a famous jockey instead of becoming an actor.

When George retired as a jockey he did not retire from horse racing. In 1968 he accepted a job as a race track official. He worked as a clerk, placing judge, and patrol judge. He was a steward, the highest level race track official who is responsible for enforcing the rules, at some minor tracks. George said that he made it big when he became an official at Del Mar, Santa Anita, and Hollywood Park. He was highly respected as a race track official, and he retired for good in 1990. The last post he held was a prominent one – assistant racing secretary.

As a jockey and race track official, George was more than willing to talk to all reporters, he bent over backwards to accept speaking engagements, supported service clubs by appearing in their programs, and even did radio promos for special events. But now George lives reclusively in his Palm Springs home. He no longer hobnobs with the celebrities whose autographed photographs can be found among his treasure trove of memorabilia. Upon retirement he typically declined all requests for interviews outright, and would furtively venture out for only one reason and that was to play golf. He did briefly take up drawing and painting as a hobby, and well-known racehorses were the sole subject of his artwork.

In the spring of 2000, “Celebrating the American Spirit of Sport” was the theme of the Japanese American National Museum’s Annual Dinner held at the Century Plaza Hotel. George Taniguchi was among the pioneer Nikkei athletes and contemporary sports stars who were honored that evening. With twelve hundred dinner attendees enthusiastically cheering and clapping, it seemed as though the Nisei jockey was in the winner’s circle once again.

* The original version of this article first appeared in Imperial Valley Pioneer (August 2006), the newsletter of the Imperial County Historical Society.

© 2020 Tim Asamen