Kimi Gengo Tagawa achieved early renown for her poetry, winning prizes and publishing a volume of verse while still in her twenties. Conversely, the long artistic career of her husband, Bunji Tagawa, did not take off until after his thirtieth birthday.

Bunji Tagawa was born in Japan on August 13, 1904. Daikichiro Tagawa, his father, was a Japanese Christian lawyer, journalist, and statesman who later served as president of Meiji University. The elder Tagawa served multiple terms in the Diet as an independent representative from his native Nagasaki, and became renowned for his liberal and progressive views and his advocacy of world disarmament. In 1917, Daikichiro Tagawa spent several months in prison for writing an article criticizing the government. In 1921-22, he spent an extended period in the United States as a member of the Japanese delegation at the Washington Naval Conference, and made a speaking tour.

Bunji Tagawa arrived in the United States in May 1922. According to family legend, he initially enrolled at a small college in Kansas that was the alma mater of his tutor in Japan, and intended to leave after his studies. However, after the great Kanto earthquake of 1923, he feared his family had been killed and decided to stay in the United States.

In any event, he enrolled at the University of Kansas, majoring in psychology, and obtained a degree in 1926. He then enrolled as a graduate student in Philosophy at Cornell University. During his time at Cornell, Bunji Tagawa was offered membership in the honorary scholarship society, Phi Beta Kappa, but he refused the coveted honor, informing the committee: “It is not my policy to label anybody, and I must refuse to be labeled myself." It is not clear whether he completed his Ph.D. at Cornell—according to family legend, he received his degree but later destroyed the only copy of his doctoral thesis.

Whatever the case, after leaving Cornell in 1930, Tagawa moved to Brooklyn. In February 1932, he married Kimi Gengo, whom he had met at Cornell. Once settled in New York, Tagawa became active as a visual artist, although he had not previously studied art, and participated in several exhibitions of water color and tempera work.

In 1932, his watercolors were featured as part of a show at the 96th Street branch of the New York Public Library. The following year, his work “Pearl Tavern” was featured in the Whitney Museum’s First Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Sculpture, Watercolors and Prints. In April 1937, Tagawa’s tempera painting “Freeville Station” was included in an exhibition of Nisei artists in New York sponsored by the Tozai Club, an elite Japanese businessmen’s club.

In addition to displaying his painting, Tagawa turned to book illustration and graphic design. In fact, his first published work was a pencil drawing of his wife that served as a frontispiece for her poetry volume To One Who Mourns at the Death of the Emperor.

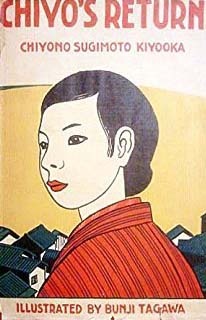

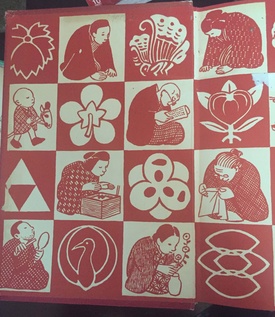

However, his breakthrough assignment was the illustrations he provided for the 1935 book Chiyo’s Return, by author Chiyono Sugimoto Kiyooka. Tagawa supplied a set of woodcut-style illustrations of Japanese scenes that resembled a cross between Victorian children’s books and Ukiyo-e prints. In a review of Chiyo’s Return, author Pearl S. Buck praised the designs as “charming woodcuts [that are] well in keeping with the spirit of this autobiographical story of contemporary Japan.” He followed with further deisgns for Japanese-themed chidren’s books. In 1936, he did illustrations for Elinor Hedrick and Kathryne Van Noy’s book Kites and Kimonos. The following year, he provided images for Lillian Homes Strack’s book, Swords and Iris: Stories of the Japanese Doll Festivals.

In 1936, Tagawa gained special attention for a set of black and white illustrations that he contributed to accompany “Prayer to a Blind Goddess," a short story by Mona Gardner that appeared in The Delineator. Tagawa’s illustrations consisted of drawings of a hard-working but destitute farmer’s family in northern Japan. The editor of The Delineator, Oscar Graeve, singled Tagawa’s work out for praise: “The charming sketches in this issue are his first magazine work. We are doubly proud to give you both a new artist and a new author."

By the end of the 1930s, Tagawa received more regular work as a freelance graphic designer and mapmaker, working through the firm Graphic Associates, and by his own estimation produced some 3,000 maps in the decade that followed. He later stated that map design was a good field for an artist to enter because of the lack of competition.

In 1940 he began contributing charts and maps for a series of books and pamphlets sponsored by The Foreign Policy Association and designed by Graphic Associates (on some of them he worked together with artist-activist Jack Chen). These assignments continued through all the years of World War II. During these years, Tagawa worked on a pair of notable projects involving African Americans. In 1941, he illustrated the pamphlet, “The Negro and Defense: A Test of Democracy” for the Council for Democracy. In 1945, he provided a series of charts and graphics for Black Metropolis, St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton’s landmark sociological study of Chicago’s Black Belt.

Considering Daikichiro Tagawa’s long record of public activity, it is curious that his son Bunji does not seem to have been politically engaged in the period surrounding World War II. Perhaps he either did not hold strong views, or due to his immigration status (he was formally an illegal alien) he felt a need to be circumspect. True, in the days following Pearl Harbor, he joined with other Japanese artists in New York to sign a resolution. It strongly condemned “the unprovoked and vicious attack” of militarist Japan and expressed “determination to support the United States to the utmost as artists and men, and further, to bear arms if necessary to insure the final victory for the Democratic forces of the world.” (Tagawa, as a 37 year-old with a family, had little chance of being called for service).

However, unlike such artists as Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Isamu Noguchi, and Taro Yashima, he does not seem to have served with wartime U.S. government agencies or joined anti-Fascist groups such as the Japanese American Committee for Democracy. Tagawa was nonetheless affected by the Pacific War. As an “enemy alien,” he was subjected to a curfew and other restrictions. According to Tagawa’s granddaughter, Nara Garber, he was placed under house arrest at some point during the conflict, and his wife Kimi and his friends, whose movements were unrestricted, served as couriers for him.

Despite the limitations, Tagawa maintained his practice, and expanded it over time. A postwar newspaper article stated that Tagawa was responsible for drawing the maps and charts used in many textbooks in the United States, and also drew maps for government agencies such as the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) that required maps of housing sites (It is possible that Tagawa helped design the maps that were used by FHA officials in their notorious practice of “redlining” neighborhoods to exclude African Americans and other minorities).

In the early 1950s, Tagawa returned to illustrating children’s books for H. Schuman (later Abelard-Schuman), Harcourt-Brace, Barrows, and other presses. His most prominent assignment was as an illustrator and producer of information graphics for the magazine Scientific American. Tagawa continued working for Scientific American through the mid-1980s, and produced a large corpus of images. In addition to great beauty, his work shows astounding technical proficiency, especially for a man with no scientific training. In 1967 he was invited by Scientific American to serve as one of judges for the Leonardo Trophy in the First International Paper Airplane Competition. In his bio for the competition Tagawa listed himself as a Sage Fellow in Philosophy at Cornell, and instructor in origami at P.S. 29, New York.

Tagawa spent his later years living comfortably in Brooklyn. In 1954, shortly after the McCarran-Walter Immigration opened naturalization to Japanese, he became a US citizen. He continued to paint in watercolors, and took a particular interest in mushrooms.

The Tagawas went on frequent hikes in the countryside and brought home the mushrooms they found, which Bunji Tagawa then used as subjects for his paintings. His daughter Ikuyo Tagawa-Garber estimated that Tagawa painted more than 700 mushroom studies during the last 10 to 15 years of his life. Along with his collaborator Gary Lincoff, he produced a guide to poisonous mushrooms in the New York area for the New York Mycological Society. Tagawa hoped to catalogue all of the mushrooms in North America in a book with Lincoff featuring his watercolors, but he was unable to complete the work. A sampling of Tagawa’s mushroom watercolor paintings was displayed in an exhibition at LaGuardia Community College in 1998.

Bunji Tagawa died of stomach cancer in 1988, just months after his wife Kimi Tagawa. He was not widely known at the time of his passing. However, Amanda Montanez’s 2018 article in Scientific American, “Remembering Bunji Tagawa,” helped jump-start a reconsideration of the man and his oeuvre.

© 2020 Greg Robinson