One of the larger causes of Executive Order 9066, and the U.S. government’s wartime confinement of Japanese Americans, can be found in the widespread expressions of race-based fear and suspicion against West Coast Issei and Nisei in the years before Pearl Harbor. During these years hate merchants, both on the West Coast and beyond, repeatedly accused Japanese Americans of being spies and saboteurs for Tokyo—launching their charges on the flimsiest of evidence or no evidence at all.

As I reported in my book A Tragedy of Democracy (2009), during this period the well-known evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson called on the federal government to take action against Issei truck farmers, since in case of war with Japan they could poison vegetables. Blayney F. Matthews, a former FBI agent, spread wild stories about Issei farmers spraying their crops with arsenic.

Perhaps the most outrageous rumor merchant was Lail T. Kane, a marine surveyor for the County of Los Angeles and former U.S. Naval Reserve Officer. Lane charged publicly that Japanese fishing vessels in Southern California ports were in fact concealed torpedo boats for the Japanese navy that could be taken out and converted at short notice in case of war. Even after being authoritatively debunked, these stories remained in the public mind.

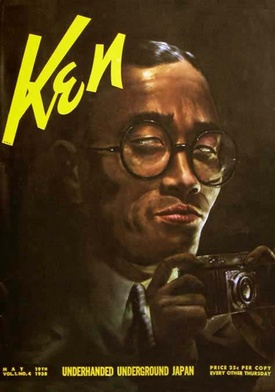

One particular source of racial hysteria was Ken Magazine, which not only joined the parade of accusations about Japanese Americans on the West but projected them at a nationwide level.

Ken was founded in April 1938, as a large-format monthly magazine. It was directed by the team of publisher David A. Smart and editor Arnold Gingrich, who had earlier founded Esquire magazine. It was originally designed as a left-leaning anti-Fascist publication, and Jay Allen, who had distinguished himself by his reporting on the Spanish Civil War, was named as the first editor.

Allen soon left the magazine, and the editorship was given to the left-wing investigative journalist George Seldes. Seldes later recalled that he was initially invited to co-edit the magazine with the famous novelist and activist Ernest Hemingway and with popular science writer Paul de Kruif. In the end, neither of the other two worked on the direction of the magazine, although the magazine featured Hemingway’s reports on the Spanish Civil War.

In keeping with Ken’s anti-fascist focus, Seldes commissioned John L. Spivak to write articles. Spivak, an investigative journalist and frequent contributor to the American Marxist magazine New Masses, had toured Europe during the mid-1930s and had produced Europe Under the Terror (1936), a popular volume on conditions in Central Europe. It featured sensationalistic and improbable stories about German and Italian spying activities. Spivak began reporting for Ken regarding Nazi spying activities in the United States and Latin America (His articles would be collected into a book, Secret Armies (1939). In addition, he soon turned to focus on alleged Japanese spying and secret activities on the West Coast.1

The first reports on Japanese spies appeared in Ken’s inaugural issue in April 1938. An article entitled “A Label for Propaganda” offered an exposé of alleged Japanese propaganda activities in the US. Repeating the wild charges that Issei- and Nisei-owned fishing boats were set for use by the Japanese navy in case of war, Ken listed the names of ten boats owned by Japanese nationals but flying the American flag that the article accused of suspicious activities. A second article, “The Jap-Jittery Northwest,” recounted fears over Japanese activities in Western Canada.

In the months that followed, Ken continued its reportage. For example, in December 1938, it contained an article, “The German-Japanese Spy Alliance,” that detailed information sharing among Nazi agents with their Japanese counterparts. In the April 1939 of Ken appeared another exposé, “The Threat to San Diego,” which discussed in detail the movements of Japanese ships off the California coast, and updated the previous charges that spies were using the boats for suspicious activities such as taking photographs of American defense installations with telephoto lenses.

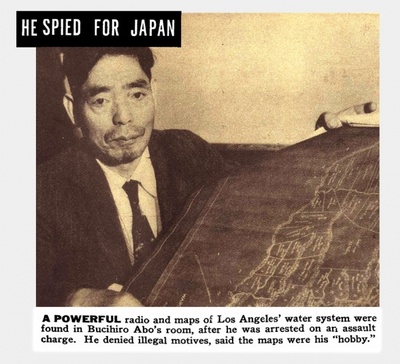

Perhaps Ken’s most sensational report was an article in the May 1939 issue, “How American Police Officials Peddle Secrets to the Japs.” The article claimed documentary proof showing that agents of the Los Angeles Police Department had turned over valuable information to local Japanese and Italian consular officials, which “evidence” in turn was discovered by the Office of Naval Intelligence.

Named in the article were James E. Davis and William Hynes, former chiefs of the notorious “red squad” of the Los Angeles Police Department, who were alleged to have fingered Japanese suspected of being communists and provided Japanese consulates with information on their activities (which then was transferred further on to U.S. Naval intelligence).

The magazine also alleged that U.S. Army reserve officers had constituted a “secret army” and had stockpiled $78,000 worth of bombs and munitions in a Los Angeles warehouse. These charges vehemently denied by Los Angeles police officials, who claimed that they handed out routine information to all consulates, and by Mayor Fletcher Bowron, who called the story “pretty flat.” Local Japanese consul Kwan Yoshida admitted that he had been interviewed by Ken reporters but claimed that his answers had been distorted.

Curiously, even as Ken beat the drumbeat of suspicion against Japanese nationals, it offered praise and encouragement for the second generation. For example, the December 1938 issue featured a positive article by Khyber Forrester lauding the Nisei both as good Americans and as a bridge to Japan.

Forrester assured his readers that the State Department, the Secret Service and other government agencies felt sure of the loyalty of the young Japanese in America. “Increasingly it is recognized that these Americans (of Japanese parentage) most of whom reside in California are worth several times the weight of the army and navy in maintaining peace in the Pacific area.” The article declared that state and federal officials had learned the pitfalls of antagonizing Japanese immigrants and were now using public schools as a motor for encouraging integration—some educators foresaw complete social mixing and the disappearance of the “Japanese problem” in California within 30 years.

In May 1939, another positive article, Ernest Paynter’s “The Twain Can Meet,” appeared in Ken. In it, Paynter reported that a study of young Nisei in San Pedro had demonstrated that they were an exceptionally industrious, moral, and easily assimilated population, growing into good Americans. “In the event of war,” the article concluded, “Japanese in America will be as loyal as any other nationality, more so than some.”

For all the attention (and outrage) it received from Japanese Americans, Ken proved to be a rather ephemeral publication. By January 1939, editor Gingrich announced that he intended to wind up operations, and Ken suspended publication after its August 1939 issue. John Spivak meanwhile expanded his dispatches about Japanese espionage into the book Honorable Spy (1939). In the months before Pearl Harbor, he revived his wild charges about Japanese espionage in a new magazine, Friday, but it proved even shorter-lived than Ken.

It is not clear how influential Ken was, by itself, in inciting prejudice against Japanese Americans. Journalist Larry Tajiri claimed that once Ken helped give credence to the wild charges about alien fishing boats being responsible for spying, bills were introduced in the California legislature to bar Japanese aliens from being granted fishing licenses. (These bills were blocked during the prewar years, but a similar measure was enacted in 1943 following mass removal of Issei and Nisei).

What is more, the articles that appeared in Ken seem to have been more an aspect of Spivak’s and the editors’ larger anti-Nazi agenda than a product of a particular racist agenda against Japanese. Still, what is certain is that Ken contributed to the uneasy climate of West Coast public attitudes towards Japanese Americans. The visibility of such wild rumors during the prewar period, even before Pearl Harbor lent them greater plausibility, helps explain why government officials during 1942 were ready to believe the worst about Japanese Americans, without credible evidence of any wrongdoing, and thereafter to act on them.

In brief, the history of Ken nonetheless reminds us of the endemic suspicion against Japanese Americans during the prewar years, and of its place in the long and tangled roots of mass confinement.

Note:

1. There were also a series of articles by Spivak on Japanese spies in Latin America, focusing on Panama, but those are sufficiently distinct that they deserve to be treated in a separate article.

* Maxime Minne contributed to the research for this article.

© 2019 Greg Robinson