The continuation of Lillian Michiko Blakey's story.

Right after the craft show, I got busy with my first real art piece. I am still mystified as to why I chose to create a nonrepresentational piece of art. “White Night” was an abstract landscape completely created in varying tones of point fabric. Upon reflection today, I find myself thinking this is an odd way of representing night. The other strange thing is that abstract expressionism of the 60s have never been of intrinsic interest to me. As I grow older, I search for meaning increasingly in the world of realism. Today, decades later, I find meaning only in telling the story of my family during and after the war years, art of social activism.

One of the most difficult things I have to do what’s to play the role of artists on display at the opening of my shows. People come to drink wine, ask questions, see who else is there, be seen, and perhaps to buy a piece. I was a very shy person who valued private space and it almost killed me to be packaged, publicized, and put on display for public scrutiny.

One absurd question repeated by many people was: “And how long have you been in this country, dear?” I replied, “I was born here. So were my parents. And my grandparents, all four of them, came when they were very young.” The answer was invariably, “Oh my goodness, that is a long time.” What this question had to do with my artwork defies logic. It seems as if people automatically assume that one is a foreigner when one does things such as showing artwork, looking as I did, and with the name they cannot pronounce.

Then, for 10 years after the show no one asked this question. Then suddenly it was being asked again quite regularly. The people who were now asking me were the new Canadian Asians. It took me quite a while to catch on to why they were asking me where I was born. I kept on saying, “I was born here.” And they would walk away, looking puzzled. I realized after time that what they were searching for was another familiar person with whom they might have something in common this totally alien culture. At first, I was reluctant to say that my family originally had when the question was asked by a Chinese or Korean person, because of the inhumane treatment their countrymen had received at the hands of the Japanese. But I was relieved to find that they harbored no resentment. Any Asian, even a Japanese, was better than none.

Years later, I received a review in The Globe and Mail which described my work has appeared to be “heavily influenced by the surface declaration techniques of Art Nouveau. A closer inspection shows that go directly to the source that inspired Art Nouveau in the first place: Oriental Art.”

The strange thing about this observation is that I was not consciously following the conventions of either Art Nouveau or Asian art. All I was trying to do was to create harmony of design. Perhaps there was a part of me that was so Japanese that it haunted my subconscious mind and manifested itself in how I perceived and interpreted the world in my art. My second husband believed in the reality and persistence of race memory. Maybe there is something in this theory, after all.

For me, the most important element in my work has always been spatial relationships. Not the actual subject matter. The handling of space is what conveys the meaning. I have always concentrated naturally on the negative space, the space around the figures which, to the Western eye, is the space leftover, the space that does not count. I feel that awareness is heightened if you concentrate on that which is not obvious. To some people, this is a very odd way of looking at things.

Perhaps this ability to focus on relationships is a gift from my Japanese heritage. The Japanese have always been masters of manipulating space in a peculiar way. In a tiny country so incredibly crowded with people, they were able to find enough private space to make tiny gardens and create the illusion of vast expenses – raked sand that appears as a wind-rippled beach where no man has trod; a tiny pool that takes on the dimensions of a large pond complete with fish, reeds, and lily pads; bonsai trees that are only a few inches high but deceive the eye and make you think they are full grown trees.

I had many shows with my soft sculpture wall hangings and exhibited with many galleries, but in 1980, with the death of both my father and my marriage, I decided that my professional name Michi should also die. I removed everything from the gallery; simply said that I would be in touch sometime. Since that time I have experienced much, but I have never sold anything again. I had never really wanted to become an artist known for wall hangings. I have never wanted to be Michi.

After my divorce, I focused completely on teaching, working with the most marginalized children in Toronto. I used art to explore identity and literacy and eventually became a consultant who is doing groundbreaking work. I encouraged children to honor their heritage and to explore their family stories. Everything I do today in my artwork, I learned from the children.

I was 60 years old before I returned to the world of art. I became the first non-white President of Canada’s longest continuing artists’ group, the Ontario Society of Artists and served on the Board of Directors for the John B. Aird Gallery in the Macdonald block of the Government of Ontario. I have works in the permanent collections of the Government of Ontario Art Collection and of the Nikkei National Museum in B.C.

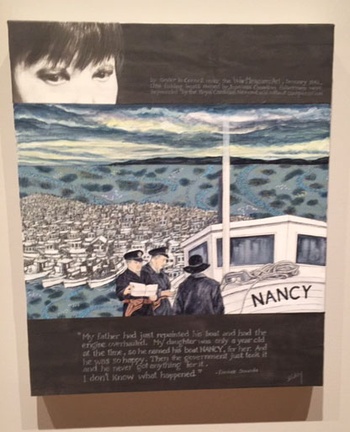

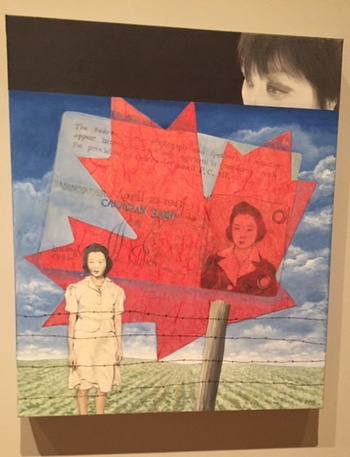

I finally had the courage to tell the awful story of what had happened to my family during and after the war years. It is the story of every single Japanese Canadian whose civil rights were stolen from them by the government, who were incarcerated and lost everything. It has taken me all my life to fully understand what citizenship truly means and that no government has the right to persecute its citizens.

As a result, my current work focuses solely on social commentary and raising social awareness. I have grown much in my journey as an artist and in my remaining years I hope to make a small impact in ensuring justice, not only for my family and all Japanese Canadians who endured the injustice and debilitating experience of justified racism, but for all immigrants new to Canada. The only regret I have is that I chose my husband’s surname in my professional work. While I included Michiko, I now believe I should have kept my family name, Yano.

I feel vindicated that what I am doing is important, especially in my participation as one of the eight artists in the Royal Ontario Museum’s courageous exhibition, Being Japanese Canadians: Reflections of a Broken World. It’s sad, but it took a major Canadian institution to bring to light the story of Japanese Canadians as an integral part of Canadian history, albeit a shameful one. We had done nothing but be the best Canadians possible.

Through my work, I want to be a role model for other Japanese Canadian artists so that they can feel proud of who they are, find a courageous voice and express their creativity through their own stories. I am especially proud of the Yonsei artists, film makers, playwrights, and musicians who find inspiration in our story in ways that few artists in my generation could not. They are fearless and so talented! Perhaps the Issei and Nisei were wise in protecting their children and grandchildren from the horrors of WW2. Their silence made future generations move on without fear, without anger, without humiliation.”

* * * * *

Lillian’s work is featured in the Being Japanese Canadian: Reflections on a Broken World exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto until August 5, 2019.

© 2019 Norm Ibuki