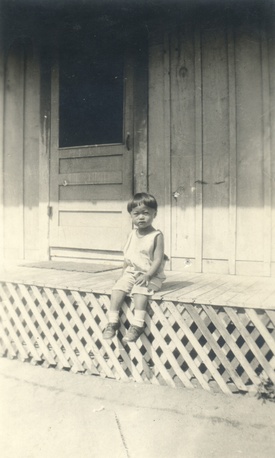

The son of two Japanese immigrants who met and married in Los Angeles, Kataoka was born in 1934 in the city’s Jefferson Park neighborhood, then home to a large Japanese American community. His mother was a housewife and his father and uncle worked for a time as partners in a Firestone tire dealership in downtown Los Angeles. Later, his father rented 10 acres in the city of Azusa, located in the nearby San Gabriel Valley, where he raised flowers and strawberries.

The family spoke Japanese at home and Kataoka learned English while attending elementary school in Azusa. He was a second-grader in 1942 when President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the incarceration of Japanese Americans. Without being told where they were going, Kataoka and his parents were taken first to an assembly center on the Pomona Fairgrounds, where his sister was born, and later to Heart Mountain War Relocation Center in Wyoming, where they were held until 1945.

As one would expect, this experience had a profound impact on Kataoka, as it did on other incarcerated Japanese Americans and their families across generations. While it would be an oversimplification to draw too direct a line to his work as a communications designer, there is no doubt that Kataoka’s incarceration and subsequent coming-of-age in 1950s America tuned his attention to racial hierarchies and social inequities that he aimed to address throughout his career.

Kataoka remembers the barbed wire fence and guard towers of Heart Mountain, “just like in the movies, like prison, with soldiers and guns up there,” with no distinction made “between whether you were born in the US or not.” While in the camp, he recalls, “I began to learn what it meant to be called ‘Jap’… Occasionally, the administration of the camp, which was all white, let us out on little tours, for children—field trips to Cody, Wyoming, which was one of those single-street towns. And you would see signs in the windows, ‘No Japs welcome here,’ all kinds of handmade signs. Even from a child’s point of view you could tell the field trip was ridiculous.”1

Towards the end of the war, the US government began releasing prisoners under the supervision of sponsoring families and agencies. Seabrook Farms, a large produce company that needed workers, sponsored hundreds through this program to move to New Jersey and work for them. Warned “not to return to California because it was dangerous, with the Ku Klux Klan and anti-Yellow, anti-Japanese”2 feelings, the Kataokas accepted the Seabrook sponsorship. In 1945, they traveled from Heart Mountain by train with a group of about 100 people to the newly-constructed worker housing of Seabrook Farms Village.

Kataoka’s parents worked—one on nightshift, one on dayshift—processing and packaging frozen vegetables at Seabrook Farms. When he turned 13, he was hired as a “bean checker” to weigh the produce picked by African American migrant workers, mainly from Jamaica, who followed the harvest from Florida up the East Coast. “It was a very confusing period for Japanese Americans,” he recounts, sometimes being treated as white, sometimes not-white, depending on where they were.3

As a teenager living in the small town of Bridgeton, New Jersey, Kataoka saw that everybody in town went to the movies every Saturday. “You saw everybody—the principal, the teachers—but you never saw any African Americans.” At first, he didn’t question this, thinking that maybe they simply didn’t go to the movies. Then, he noticed all the African Americans were upstairs in the balcony. He learned more about segregation and the realities of Jim Crow on a high school field trip to Washington, D.C., “to see the Capitol and see how democracy works and all that bullshit,” he recalls. Traveling across New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, he noticed that the bus driver would, periodically, pull over in the middle of nowhere and the Black students would just know to get out, if they needed a latrine. “They had to go out and pee in the woods as they weren’t allowed to do that [at the rest stops used by other students]. This is 1951!”4

After graduating from Bridgeton High School, Kataoka was accepted to the Rhode Island School of Design. He traveled to Providence to take a placement test and find a place to live, as the school had no dorms. He was given a list of places that took student lodgers and found, after knocking on many doors, that all gave one reason or another they could not accommodate him. This icy reception changed his mind about attending the school. He called his mother and father to tell them, “Something’s wrong here. I’m not going to go to this school.”5 Kataoka had also been accepted to UCLA and, in February 1952, enrolled there as a freshman, instead.

Kataoka graduated with a BA in arts education in 1957. During the Korean War, male undergraduates at UCLA were required to go through ROTC. After graduation, Kataoka continued his service in the Army Reserves as an armored tank officer (1957–65). In 1959, he earned an MA in Communication Design. He began working as a graphic designer for clients, such as Kawai piano, and teaching at Mount St. Mary’s College in Los Angeles. In 1966, Kataoka joined UCLA’s Department of Art, Art History, and Design, as it was then known, as a tenure-track assistant professor and the first person of color on the department faculty.

Over 40 years at UCLA, Kataoka was responsible for hiring the few other faculty of color who joined his department. In all that time, he says, he had no more than four African American students. A 1978 article in the Los Angeles Times argued that Kataoka’s work could ease the trauma of court-ordered busing, stating that his interactive projects with schools “demonstrated that the simple technology of videotape could help break down racial barriers between children and make integration more peaceful than it otherwise might be.”6

While his efforts to democratize and decentralize art making were immensely fruitful and inspiring to generations, Kataoka did not receive due credit during his professional career, a fact he attributes, with great caution and internal conflict, to racial bias. Former student DK Redmond, President of Heart and Soul Design Communications in Inglewood, California, agrees: “Mits designed and built the first citywide, two-way cable television system in the US… he organized a virtual conference with Buckminster Fuller, Marshall McLuhan, and Governor Jerry Brown, and he was chair of the department three times. Still, they never made him a full professor. Really? Come on.”

Despite the racial politics of promotion, among his former students, there is no doubt of Kataoka’s impact. Long after retirement, Kataoka kept in touch with dozens of former students, among them leaders in design and new media who are also people of color, including John Maeda, former President of the Rhode Island School of Design, Georg Kochi, longtime trustee of the Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum, and TR Lee and DK Redmond quoted above. All credit Kataoka as an inspiration and this recognition, more than any other, bespeaks his legacy.

Mits Kataoka passed away on May 24, 2018 in Pasadena, CA after a long illness. He leaves behind his wife Susan McCoin; son Mark Kataoka and wife Cheryl Lai of Arlington, VA; granddaughter Marisa Kataoka of San Francisco, CA; and grandson Nolan Kataoka of Arlington, VA. His sister Lilly Kawashiri and her husband Shig Kawashiri and their family also survive him. His parents Nao Hatada Kataoka and Kiichiro Kataoka predeceased him, as did his first wife, Irene Wakamatsu, DDS, who died shortly after their son Mark was born.

Interview transcriptions are available on Discover Nikkei >>

Notes:

1. Jennifer Cool, interview with Mits Kataoka, September 15, 2017.

2. Jennifer Cool, interview with Mits Kataoka, September 15, 2017.

3. Jennifer Cool, interview with Mits Kataoka, September 15, 2017.

4. Jennifer Cool, interview with Mits Kataoka, September 15, 2017.

5. Jennifer Cool, interview with Mits Kataoka, September 15, 2017.

6. “How Video Could Ease Busing Trauma,” Andrea L. Rich, Los Angeles Times, Sun., March 6, 1978.

© 2019 Jennifer Cool