Mitsuru “Mits” Kataoka, was an entrepreneurial visionary who fostered artistic explorations of electronic media among generations of students and colleagues at UCLA’s department of Design Media Arts, where he taught for nearly forty years. Decades before YouTube and smartphones, he saw the transformative potential of electronic communications and worked to put emerging technologies in the hands of artists, designers, and students through innovative partnerships with technology companies. Over his long career, he worked on experimental projects with collaborators as diverse as Marshall McLuhan, Buckminster Fuller, William Wegman, and Nam June Paik.

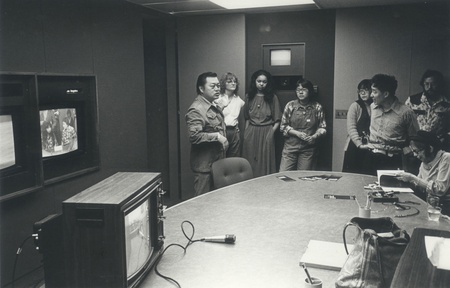

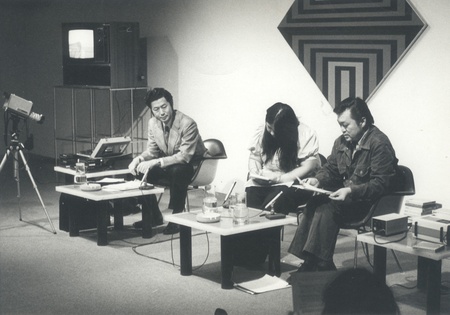

In 1969, Kataoka introduced video and computer media courses to UCLA’s design department, leading the program’s expansion into new media. In 1970, fifteen years before the MIT Media Lab opened, Kataoka conceived and founded the first art and design video research laboratory outside the entertainment industry. The laboratory was the incubator in which John Whitney Sr. began to teach his first computer graphics classes. Throughout the 1970s, it was a catalyst for the exploration of video art, hosting such artists as Nam June Paik, William Wegman, Spaghetti Factory, Kitchen, Ant Farm, David Ross, Shigeko Kubota, Steina and Woody Vasulka, and Peter D’Agostino, among many others.

Kataoka pursued a democratized, decentralized vision of art and design that could respond to a “diversity of social and cultural and geographical environments.”1 Long before consumer video cameras were available, he organized exchanges of video “letters” among schoolchildren, first across the variegated expanse of Greater Los Angeles, from inner-city Watts to suburban Irvine in Orange County, and later across the globe via a “video pen pal” network involving schools in Yemen, Ghana, Japan, France, Israel, and Sri Lanka. “When groups are isolated from each other,” Kataoka explained, “they develop myths, perceptions about each other2.” He used electronic communications as a creative way to bridge cultural difference and break down stereotypes.

When Kataoka joined the UCLA School of the Arts and Architecture in 1968, his faculty colleagues were working in more traditional media, such as industrial and graphic design, textiles, and painting. As a young professor at the start of his career, Kataoka saw this as an opportunity to research the art and design possibilities of new electronic technologies. At the time, video could not be edited and its image quality was far inferior to film. UCLA’s film and television departments focused on the professional broadcast industry and had no interest in experimental media. “People laughed at me in the beginning,” said Kataoka, in a 2017 interview.3

American electronics companies in that era also focused on audiovisual communication as a professional practice that required costly, high-end equipment. Japanese firms, in contrast, were already working to develop new consumer electronics. Kataoka began writing to electronics companies to acquire camera and recording equipment for his new lab. One of the first to reply was Masukichi Akai, founder and president of Akai. He made Kataoka’s lab at UCLA a grant of 12 Akai “portapaks”—video cameras connected to reel-to-reel videotape recorders carried in backpacks so a single person could operate both.

The Fulbright fellowship he won in 1972, which funded a year of research abroad, had a profound influence on Kataoka’s career. He spent the entire year in Japan traveling all over the country with an Akai portapak, videotaping whatever was going on, experimenting with the mobility and intimate scale of the medium. Video at the time had no clean edit capability and Kataoka saw this, not as a drawback, but an “opportunity to look at and examine things, activities, in real time.” “Everything I did was real time,” he explained in a 2017 interview. “Everything from beggars in the street to dance, people repairing, people that were doing crafts.”4

Kataoka was fascinated by the fact that, despite rapid technological development since the 1950s, Japan was still known for high quality crafts. He visited a silkscreen studio in Kyoto, where he spent hours watching and videotaping the image-making process. He also captured Kabuki theater—not what was onstage, but backstage, where he made real-time recordings of makeup artists at work. He describes videotaping “remarkable images of people that look like normal citizens… transformed into more than human beings with the tremendous Kabuki and Noh makeup.”5 His year in Japan had a lasting impact on his career, crystalizing his focus on bringing art and design into everyday life and building the relationships with electronics companies that later brought prototype technologies to his UCLA lab for students and colleagues to experiment with.

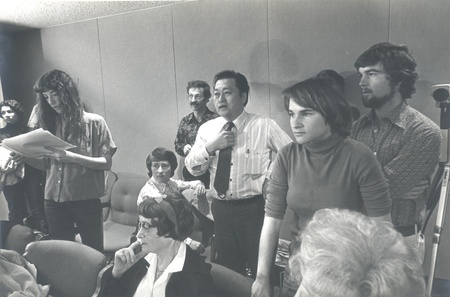

In the early 1970s, Kataoka pioneered interactive video, developing the first two-way, decentralized, citywide cable television system in the US for the Irvine School District. Elementary school students ran the cameras, made their own programs, and cablecast them site to site. “They are communicating peer to peer,” said Kataoka in a 1974 news story. “Usually in a school situation, it is from an adult authority down to the child. This way, the teacher is less and less the only source of information.”6 In 1978, Marshall McLuhan, Buckminster Fuller, and California Governor Jerry Brown participated in the Irvine Satellite Conference, which Kataoka organized to build support for satellite-televised interactive activities among schools, communities, and institutions like libraries and museums.

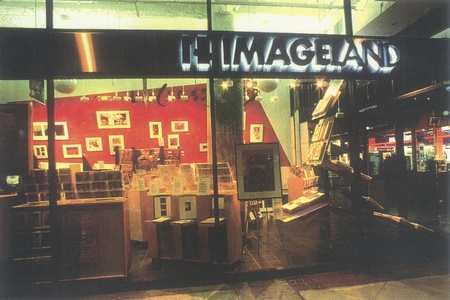

In the early 1980s, Kataoka designed a prototype for digital inkjet printing and organized two highly influential joint ventures with Japanese electronics companies: JetGraphix with Fuji, Mitsui, and UCLA in 1983 and Imageland with Canon, Inc., and CPI Corporation in 1989. JetGraphix was one of the first digital output centers in the world. Imageland had digital graphic design centers in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Tokyo. Kataoka’s design students at UCLA operated Imageland’s US studios where artists and designers used digital color copiers networked with Sun Microsystems work stations, and later Macintosh computers, to output high quality prints. In the 1990s, Kataoka turned his energies to designing interactive video networks for museums and other cultural institutions. He was also instrumental in recruiting new faculty to UCLA’s department of Design and Media Arts, building the new media curriculum and increasing faculty diversity.

Kataoka was a strategist and catalyst. His legacy rests less in particular designs or prototypes and more in his early recognition of the potential of electronic media to breakdown the boundaries separating art producers from art consumers. Indeed, decentralizing media making and flattening traditional hierarchies—from teacher/student to broadcaster/viewer—was an overarching goal of his work. His strategy was to get new technologies into the hands of artists, students, and schoolchildren and let them play and experiment. As Tien-Rein Lee, one of Kataoka’s students in the 1980s and current President of Chinese Culture University in Taiwan, recalls, “Mits was always giving us new equipment to try, an advanced camera or something still in prototype, and saying ‘just give it a try, see what you can do.’ That was very inspiring.”7

To bring a steady stream of new equipment to his lab, Kataoka had to be entrepreneurial and reach beyond the usual sources of arts and academic funding. Throughout his career, he was broad and tireless in his pursuit of corporate grants, partnerships, and joint ventures. In this, he pioneered an approach to technological innovation that has been widely adopted in corporate and university settings (for example in programs that combine study in the arts, technology, and business). A dedicated teacher, Kataoka influenced generations of students and colleagues through his decentralized vision and practice of “peer-to-peer” media.

Learn about Mits Kataoka’s life story in Part 2 >>

Notes:

1. “Artists and Their Social Responsibility,” Mitsuru Kataoka, lecture at Sapporo American Center, Feb. 10, 1973, Sapporo Simbun, Feb. 13, 1973.

2. Orange County Daily Pilot, June 23, 1974.

3. Jennifer Cool, interview with Mits Kataoka, September 15, 2017.

4. Jennifer Cool, interview with Mits Kataoka, September 15, 2017

5. Jennifer Cool, interview with Mits Kataoka, September 15, 2017.

6. Orange County Daily Pilot, June 23, 1974.

7. Jennifer Cool, interview with Tien-Rein Lee, June 6, 2018.

© 2019 Jennifer Cool