The Japanese Canadians were among the first non-native settlers of Salt Spring Island. The 1901 census shows 59 islanders of Japanese origin. In 1941, there were 77 adults and children in 11 families. They owned about 1,040 acres of land and ran some of the island’s largest and most prosperous farms and businesses.

The history of our family in Canada began in 1896, when my great-grandfather, Kumanosuke Okano, immigrated to Canada from Hiroshima, Japan. He was followed in 1902 by my great-grandmother, Riyo Kimura Okano. My grandmother (Bachan) was born in 1904, the first Canadian baby of Japanese ancestry born in Steveston, BC.

In the beginning, it was very hard for them because they were regarded as second-class citizens. Japanese Canadians were only allowed to work in the primary industries: farming, logging, fishing, and mining. They could buy land from private persons, but were forbidden to purchase Crown Land (from the government). There was much discrimination in those days. White community groups, including a church, service group, local government members, and even some law enforcement groups rose up to protest, smashing windows, and ransacking Japanese Canadian stores and businesses.

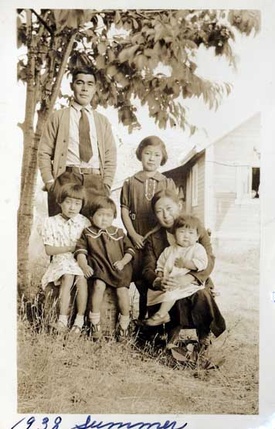

The Okano family moved to Duck Bay on Salt Spring Island when my Bachan was five years old. They were all fishers and prospered, eventually owning five boats. But when Japanese Canadian fishers were ousted from the industry through racist licensing laws, the Okano family turned to farming as many others did. In 1919, the Okanos bought and cleared 50 acres, enlarged and renovated their house, and commenced their businesses farming. They once again began to prosper.

My grandfather (Geechan) was the fifth born, in a family of five sons and one daughter. He came from a noble family. His family descended from the seventh son of the 62nd emperor of Japan. His father was wealthy and owned large tracts of land. When Geechan was 5 years old, he found a crucifix while playing on a beach. The Shinto priest told his mother that this son would go far across the sea to live a very difficult life of suffering. He brought that crucifix to Canada with him when he immigrated. He could also play the piano and violin, which he brought too, but both instruments were stolen during his World War II incarceration.

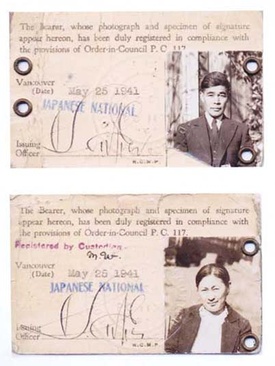

On May 25, 1941, six months before Pearl Harbor, all Japanese Canadians who were 16 years or older were photographed, fingerprinted, and made to carry registration cards. No other citizens of Canada were required to carry such cards. This stayed in effect until 1949.

Things were looking up for my grandfather’s family, the Murakamis, who lived on Salt Spring Island before the war. They were growing and shipping their famous strawberries, raspberries, and boysenberries all over BC. The berries were also shipped to the Empress Hotel, where King George the 6th and Queen Elizabeth dined and had them for their special dessert, when they visited in 1939.

On December 7, 1941, Geechan was discharged from the hospital following an appendectomy. The family was overjoyed to be reunited, and were enjoying his homecoming. He asked what the family would like to have for their 1942 Christmas, with its promised prosperity. One family member asked for a piano, another asked for a tennis court. The family’s plan was to purchase more land and to enlarge and grow the farm. Their future was bright and hopeful.

That same day, they received news of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. It struck the family like a thunderbolt and shrouded the family in a cloak of fear. They knew that something terrible was going to happen to all of the Japanese Canadians on the island.

Anti-Japanese rage and racist acts of retaliation exploded like a bomb. Two teachers and other students, who accused her of starting the war, abused my mother Alice, age 13 at the time. Students ambushed her and stoned her as she went to and from the school that her family had donated money to build.

The Ministry of Justice was empowered to remove and detain any and all persons of the Japanese race. It didn’t distinguish between Canadian citizens and aliens. Police entered and searched Japanese Canadian homes without warrants; curfews were put into place, and fishing boats, automobiles, homes, businesses, and personal belongings were seized by the government and were later sold without the families’ knowledge or consent.

They came and took my Geechan away and my Bachan instantly became a single parent with five children, aged 1–13 years old.

Soon the family was gathered up and sent away on a ship named the Princess Mary, forced to leave the island they called home. The family ended up at Hastings Park, where they had to live in animal barns. Upon their arrival, they were welcomed by the pungent smell of animal urine and feces—some still fresh in the stalls. A sea of bunk beds greeted their unbelieving eyes. Bachan was assigned to two and a half bunk beds, with loose straw for the mattresses, and two coarse blankets per bed. Bachan had a sick one year old and another asthmatic child to consider and care for. The poor quality of the food resulted in food poisoning, vomiting, and diarrhea. The toilets were troughs previously used by animals, and the smell of lime and constantly flowing water through the troughs added to their misery. There was no privacy. Hastings Park was a gathering and dispersal center for Japanese Canadian prisoners of the Canadian government. It was hell…

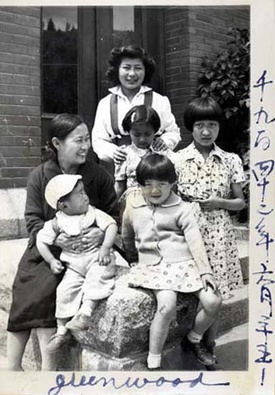

In May 1942, they were sent inland to Greenwood to live in a filthy bunkhouse, long abandoned by miners. They slept on the floor and made the best of it.

Bachan and the family didn’t know what happened to Geechan until she received a cut up letter from him, which said that he was sent by train to work on a prison road camp to build the interprovincial highway. The men lived in railroad boxcars, and in cold, damp, dirty, and crowded conditions. When his health started to fail, he became a kitchen helper. He was paid 25 cents an hour, but 25 cents was then deducted for each meal. They were also required to send at least half of their pay to their families.

In July 1942, married men were allowed to join their families if they agreed to work in the sugar beet field in Alberta, so the family was reunited in Magrath, AB. The owner of the farm that they worked on hated the Japanese. He told the townspeople to, “Treat the Japs like criminals!” The cabin they lived in was next to a pigpen and covered with so many flies that the outside walls were black.

It had a broken wood stove and Geechan got some lumber from which he made bunk beds, a table, and some benches. Their water source was shared with the farm animals. Bachan had no real kitchen and did the best she could. There were no bathing and laundry facilities. My mom was a maid to the farmer’s wife, who paid her in butter and milk. Geechan did heavy farm work, which again led to his health deteriorating.

Eventually, the family moved to another camp in Slocan, which was not much better, before they moved yet again to Rosebery internment camp, located on the other end of Slocan Lake. They suffered through freezing weather, in a 14' x 28' shack, number 208. The terrible conditions were the same, if not worse, and once again my Geechan found wood and supplies to build the family beds and some furniture.

© 2019 Gerald Tanaka