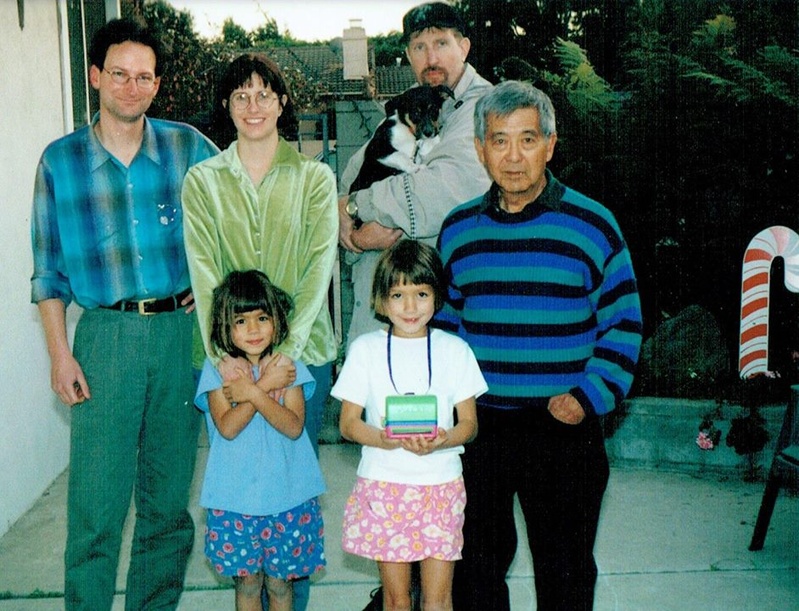

In the 17 years I was able to spend with my grandfather, Herbert Seijin Ginoza, he rarely told me about himself. Most stories I heard were told second hand, by my father or great-aunts and uncles. But the stories I heard, I remembered. He would have been reluctant to be called a hero, but to me, that’s what these stories made him. When he died, I worried that his stories would die too. That’s why, one afternoon in the middle of a power outage, I sat down to interview my father, Otis Ginoza, and to record his version of these stories. I have edited this interview for length, content, and narrative: these words are my father’s, the stories his father’s, and the message my own.

– Margaret Ginoza

* * * * *

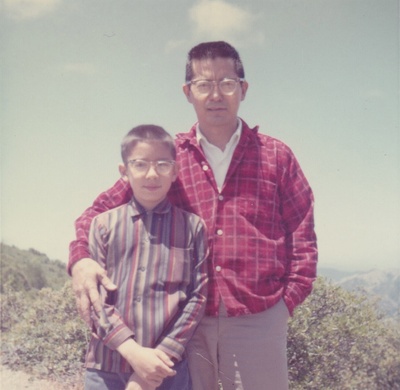

Herbert Seijin Ginoza was the child of Japanese immigrants to Hawaii, or more specifically immigrants from the Japanese province of Okinawa. His father came over to work in the cane fields originally. His mother came over as a picture bride. So he grew up on a little farm in Hawaii, and they didn’t have very much money. He was always very ambitious, and when he was younger he wanted to be an engineer.

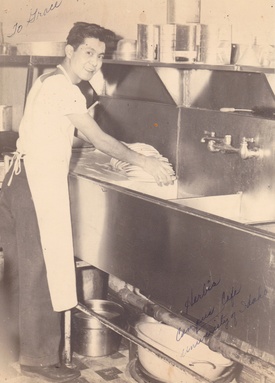

My knowledge of his life when he was younger is a little vague, because my father told me stories about his youth which were not true, and I did not discover this until I lived in Hawaii for a while and his relatives told me more accurate facts. From what the relatives tell me he ran away from home. I know he lived in Los Angeles for a time, and at some time – about the time of the Japanese internment order – my father, not wanting to be interned, left California for the Midwest, to try to continue his college education. There was no internment order affecting the Midwest so he didn’t have to worry about that. He attended various colleges. The explanation I got was that he was working his way through college, and he often ran out of money and had to drop out of school and work for a while to get more money so he could go back to school.

And he was drafted, actually illegally. At the time he was drafted, Japanese-Americans weren’t supposed to be drafted. But as my father tells the story there was a flu epidemic in whatever community he was living in and they couldn’t meet the draft quota, so they drafted him. My father was very upset at being drafted, because previously he had volunteered. The way he tells it is that he did not want to pay his college tuition, and then get drafted and lose his tuition money. So he volunteered and they turned him down saying no, Japanese-Americans are not wanted in the service. And then he paid his college tuition and got drafted.

After he was drafted, he was assigned to the Air Corps. My father tells me that he applied to transfer to the 442nd, which was the segregated army unit for Japanese-Americans, but for unknown reasons that transfer was declined and he became part of the Air Corps.

My father had four gold teeth in the front of his mouth. They were porcelain on the outside but on the inside they were gold, they were artificial teeth. The way he lost them was, when he was in the service he was on leave in town, in US Army uniform, in a bar. I guess three Marines decided they didn’t like him because he was Japanese, and beat him up and knocked out his teeth. My mother told me that he ended up in the hospital. A bunch of soldiers from his squadron went looking for the Marines the next day but never did find them.

A lot of the documents I’ve found describe him as a waist gunner. He told me he was also in charge of some kind of armaments, meaning I think he was in charge of the bombs and things like that on the plane. And he fought in World War II. He was shot down on his last mission.

I guess any time you’re shot down, it’s your last mission.

The rest of his crew landed a bit far away behind Russian lines and were not taken prisoner, but my father landed in Austria. He was wounded by ground fire as he parachuted down, and taken to a German hospital where his wounds were treated. After that a German officer and a soldier were escorting him from their prison camp. When he was being transported through a major city, it was either in Austria or Germany, that city was bombed. While they were passing through.

He told me that the air raid sirens went off, and as I child, watching all these movies about great escapes, I ask him, well did you try to escape? And he said well, I could have escaped. But he said, he didn’t think he would get very far being a Japanese-American in Germany where everybody looks German. So he thought his chances of escaping were zero, and he didn’t want to die in the bombing. So when the air raid sirens went off, the two German soldiers accompanying him just took off for the bomb shelter and he took off after them. That was his big chance to escape.

I, as little child, thought it would have been very interesting seeing a city after it was bombed. I asked him what he saw when he came up, and at that point in the story he got very upset. He said it was just horrible, horrible what he saw. He mentioned children with their arms and legs blown off, and didn’t give me much description past that, except that it was a very horrible thing.

I never asked him if he felt guilty or if he felt bad about having bombed German and Austrian cities himself, but... I think he did. I think it had a pretty big effect on him.

I remember my father getting just really upset, he was really, really upset when that news came in that President Johnson ordered the bombing of North Vietnamese cities. He kind of shouted at the TV and he said, no, he said, you should never do that, you should never bomb cities. And he underwent a political transformation. He had been a moderate republican my whole life up until then, he voted for Nixon, he voted against Kennedy, he voted for Eisenhower, he was a big Rockefeller supporter… after the bombing had been announced something changed in him and he became very much against the Vietnam war, he had been a supporter before and he was very much against it, and he pretty much in an instant became a liberal democrat and stayed that way the rest of his life.

I never asked him if he felt guilty because he is my father, and he knew that his family was proud of him. And I didn’t want him to ever think that his family was not proud of him or questioned what he did in the war.

It’s too bad Grampa couldn’t have told you these stories, but by the time you came along he didn’t want to tell these stories anymore.

© 2019 Margaret Edith Chiseko Ginoza; Otis Wright Ginoza