Charles Yasuma Yamazaki and the African American Community

Yamazaki led an interesting life, a life full of change. Born in Kochi in April 1877, he left home for better living and arrived in Seattle as a seaman in 1899.1 After working in railroad construction in Puyallup, Washington and Helena, Montana from 1899 to 1901,2 in December 1902, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy in Boston as a wardroom steward on the USS Raleigh, with a five year contract. After a month’s hospitalization in a navy hospital in March 1903 for unknown reasons, having struggled to fit in on the USS Columbia, and having been cited for disobeying orders on the USS Baltimore, he abandoned the Navy and went AWOL from the USS Baltimore in Norfolk, Virginia on Oct 28, 1903. On November 24, 1903, he wrote to the Navy to anxiously appeal for the right to surrender.3 His resignation was accepted and he was “notified that the Navy was no longer interested in his delinquency.”4

Searching for a new life, Yamazaki moved to Cleveland, Ohio in 1905 and engaged in the restaurant business until 1915.5 After some big successes and failures, he arrived in Chicago in 1915 and continued his restaurant business there. His business strategy was to work for a restaurant for a while, then take it over and run it, and then sell it to another Japanese, or keep running it in partnership with another Japanese. A good example of this strategy was the "Chicago Lunch" at 816 North Clark Street, which later became an office of the Japanese Mutual Aid Society.

Yamazaki first worked at the "Dearborn Hotel" restaurant (901 W Madison) in 1916, then purchased it and kept it as his own business until 1943.6 By 1918, he had opened “Tokyo Lunch No. 1” at 674 South State Street.7 It was not too much later that “Tokyo Lunch No. 2” opened at 551 South State Street. He also worked as a cashier at the "Thomas" restaurant on State Street from April 1922 to November 1924, the "Sun Rise" restaurant on Maxwell Street from December 1929-August 1930, and the "Indiana Restaurant" at 4248 Indiana Ave for 6 years,8 but always seemed to be looking for new business opportunities. The "Indiana Restaurant" was later owned by Frank Masuto Kono by around 1938.9

As the names, locations and owners of the restaurants Yamazaki once had owned were numerous, with so many frequent changes and joint ownerships, it is almost impossible to trace them accurately. For example, while at one time “Tokyo Lunch” was listed at 604 W Madison under the name of Yamazaki,10 the 1928-29 Chicago Directory showed three restaurants owned by Yamazaki at West Madison, one under the name of Yamazaki at 704 W. Madison and two restaurants under the name of "Sun Rise" restaurant at 645 and 731 W. Madison. Furthermore, four restaurants were listed as "Tokyo Restaurant," at 816 N. Clark, and at 551, 643 and 674 S. State. At the peak of his business career, Yamazaki had nine locations in his “Tokyo Restaurant” chain, with more than a hundred employees for all of his restaurants.11 At the time of the 1929 economic crash, restaurants known and recorded as run by Yamazaki, other than the several "Tokyo Lunch," "Chicago Lunch" and "Sun Rise" restaurants, were "Kobe Lunch" at 634 South State, a restaurant at 45 North Clark,12and another restaurant at 230 Chicago Avenue, which he kept from December 1924 to December 1929.13

In 1925, he established the Chicago Commissary & Restaurant Company at 816 N Clark14 to consolidate and better manage his restaurants, but dissolved it in 1930 due to economic depression.15 It appears that Yamazaki had to reduce the number of his restaurant businesses after 1929, and in 1939 he purchased a 135 acre truck garden farm in North Judson, Indiana to supply his Chicago restaurants. The remainder of the vegetables were sold to a company in Indianapolis, Indiana. Yamazaki also “rented 106 acres in another section of North Judson and employed on the two pieces of land approximately fifteen individuals, seven of whom were Japanese.” One of these Japanese employees had previously worked at the Japan Foreign Trade Bureau (1520 Tribune Tower), in the same building where the Japanese Consulate of Chicago was located.16

Until December 1943, Yamazaki’s life as the father of two daughters, (born in Chicago in 1919 and 1921), a successful businessman and presidentof the Chicago Japanese Restaurateur Union, (which started in August 1928 with about 40 Japanese restaurateurs17, and president of the Japanese Mutual Aid Society, was peaceful and respectable enough that he was honored by the Japanese government in 1935 and 1940.

After his arrest in December 1943, the FBI searched and found in his home small red lacquer wooden cups bearing inscriptions in Japanese characters and the emblem of the Japanese Red Cross. The investigators interrogated Yamazaki about them and continued to look for evidence of his anti-US subversive activities in vain.18

His FBI records show that his most “suspicious contacts” were his restaurants, because some of his restaurants were “located in a negro district and had been visited by many negros.”19 “At his restaurant located at 551 South State, Yamazaki employed between eighteen and twenty workers of which eight were Japanese, three African American, and the remainder white. At the restaurant at 634 South State, Yamazaki employed about fourteen individuals of which approximately eight were Japanese aliens.”20 The rest of the six employees must have been black and white. Yamazaki served approximately 75,000 meals a month in the two restaurants21 and many of the customers must have been African Americans.

We also know that Yamazaki’s contact with African Americans was not only at his restaurants, but also through the activities of the Japanese Mutual Aid Society. According to his FBI file, “Sometime in 1939 while Yamazaki was in the restaurant at 816 North Clark, a colored person introduced himself as C.C. Bates, said he was looking for the Mutual Aid Society and wanted to make a donation of certain moneys through the Mutual Aid Society for the benefit of the Japanese soldiers fighting in China. Yamazaki and Bates went to the Japanese consulate where Bates turned the money over to an employee in the office and got a receipt for this sum $200.”22

Furthermore, according to the Society’s Executive Secretary’s notes, on July 6, 1939, Bates and four other African Americans came from Detroit and donated $100 to help Japanese soldiers’ families in Japan. They had first gone to the Japanese Consulate in Chicago by themselves the previous week, but the donation was rejected. The Japanese Mutual Aid Society wrote to them to explain the situation, and Bates and his group members came back to the office of the Society with the donation.23

According to the FBI file, “Yamazaki had never seen Bates before and the next time he saw Bates was in 1940 when Bates came to Chicago and said that Takahashi was in the penitentiary and was sick and Bates requested Yamazaki to take some money to Takahashi.”24 The account continues, “Yamazaki had never heard of Takahashi and declined to take the money to Takahashi because of the demands of his business.”25

But Yamazaki must have taken to heart one of the missions of the Japanese Mutual Aid Society, that is, to provide necessary social services to Japanese, especially the sick. In the past, as one of their responsibilities, Yamazaki and other members of the Society had visited Japanese patients in hospitals, not only in Chicago, but even in Kansas City, Missouri,26 bringing Japanese meals such as sushi boxes, and magazines from Japan, as well as some pocket money. Their visits were greatly appreciated, bringing tears to the patients.27 We also know that Yamazaki’s charity activities, such as helping arrange funerals for poor Japanese, had started well before the Japanese Mutual Aid Society was even established.28

Even though Yamazaki did not know Takahashi, who was not from Chicago, and he did not intend to meet Takahashi himself, Yamazaki wrote a letter to the Department of Justice to obtain permission for one of the representatives of the Society to visit Takahashi in Springfield, Missouri.29 In response, permission for a visit was granted, and, at Yamazaki’s suggestion, Shoji Osato made the trip to Springfield, Missouri and gave Takahashi the money given to him by Bates.30

But who was C.C. Bates? Who was Takahashi? C.C. Bates was a black minister from Detroit who had been actively engaged in “The Onward Movement of America,” a black organization that that was an offshoot of a parent black organization called “The Development of Our Own,” which Takahashi had organized to disseminate pro-Japan propaganda in the early 1930s.

Yamazaki told investigators that he had no information concerning Takahashi’s activities among African Americans, and denied any pro-Japanese sympathies or knowledge of subversive activities among the Japanese in the Chicago area. He denied having any allegiance or loyalty to the Japanese emperor and desired an Allied victory. Yamazaki also stated that he had no intention of returning to Japan, and explained that, unlike most Japanese individuals, he had already made arrangements for his burial in this country after his death.31

Witnesses also testified very positively for Yamazaki, saying that he was a nice, harmless, old man, and that he was selfless and charitable, living in a dingy apartment while giving a great deal of money to help the Japanese poor, and that he was also a very dependable and kind Japanese person.32

According to the FBI file, “Yamazaki failed to reveal any evidence of being dangerous, directly engaged in causing agitation among the African Americans. Furthermore no evidence was found that the Mutual Service Centerwas being used as a meeting place for subversive purposes.” Yamazaki was given interim parole in February 1944, and the parole ended in November 1945.33

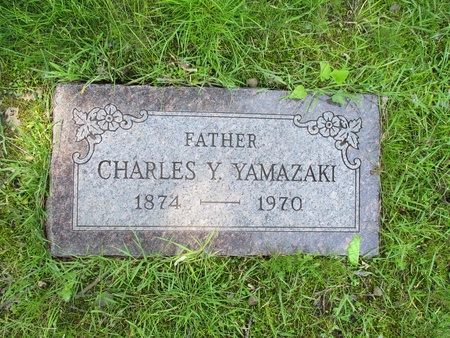

After the war, Yamazaki was very successful at peppermint farming and mint oil production. In 1953 he sold the agriculture business and from thereafter switched to the real estate/apartment business in Chicago.34 Yamazaki passed away of old age on January 27, 1970, at the age of 95.35 He became one with the soil of Illinois at Montrose Cemetery, a symbol of great accomplishment of the Japanese Mutual Aid Society, which Yamazaki himself had worked so hard for the benefit of the greater Japanese Chicagoan community. Yamazaki’s genuine and heartfelt gifts will most certainly keep contributing to the Japanese American community in Chicago over the generations to come.

Notes

1. Beikoku Nikkei-jin Hyakunen-Shi, New Japanese American News Inc, 1961, page 1318.

2. Yamazaki FBI File No 100-7471, RG 60, Box 266.

3. Yamazaki’s letter dated November 24, 1903 to Navy Department, Navy Official Military Personnel file, National Archives, St. Louis, Missouri.

4. Yamazaki FBI File No 100-7471, RG 60, Box 266.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid, WWI registration card.

8. Ibid.

9. Frank Masuto Kono File, WW II Alien Enemy Internment Case Files, 1941-1954, General Records of the Department of Justice, RG 60, Box 272, FBI Case No 100-10053, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland, World War II Draft Registration Card, 1942.

10. Chicago City Directory 1923.

11. Kaigai Nippon Jitugyo-sha no Chosa, Foreign Ministry of Japan, 1926.

12. 1920 Census.

13. Yamazaki File, RG 60, Box 266, Kono File, RG 60, Box 272.

14.1928-1929 Chicago City Directory.

15. Beikoku Nikkei-jin Hyakunen-Shi, New Japanese American News Inc, 1961, page 1318.

16. Yamazaki File, RG 60, Box 266.

17. Nichibei Jiho, August 4, 1928.

18. Yamazaki File, RG 60, Box 266.

19. ibid.

20. ibid.

21. ibid.

22. ibid.

23. Executive Secretary’s notes, 1935-1941, Japanese Mutual Aid Society of Chicago, page 230.

24. Yamazaki File, RG 60, Box 266.

25. ibid.

26. Nichibei Jiho, May 27, 1939.

27. Executive Secretary’s notes, 1935-1941, Japanese Mutual Aid Society of Chicago, pages 43,233, Nichibei Jiho, June 1, 1935.

28. Nichibei Jiho, October 29, 1932.

29. Memorandum of Bennett, director of Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, dated February 13, 1941 for the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, FBI 65-562-61.

30. Yamazaki File, RG 60, Box 266.

31. ibid.

32. ibid.

33. ibid.

34. Beikoku Nikkei-jin Hyakunen-Shi, New Japanese American News Inc, 1961, page 1318.

35. Chicago Shimpo, January 30, 1970.

© 2019 Takako Day