On December 7, 1941, the Japanese navy attacked Pearl Harbor. Although the tension between Japan and the United States catalyzed the imminence of war, the attack on the U.S. naval base in Hawaii surprised everyone.

The news spread like wildfire in Ensenada. The fishermen were on the dock that afternoon when their colleagues rushed to tell them, “War broke out, war broke out! Japan bombed Pearl Harbor!” Their initial reaction was one of great pride at knowing that the attack had been a success; however, at the same time, the news overwhelmed them with uneasiness restlessness and fear of their unknown destiny.

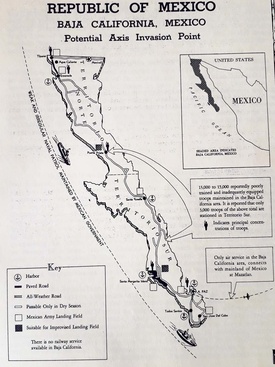

To the U.S. government, fishermen were the most dangerous group among all immigrants, namely because they knew the coasts from Canada down to the southern tip of Baja California. Since the 1910s, when they first arrived in California, they had been considered an “invading army.”

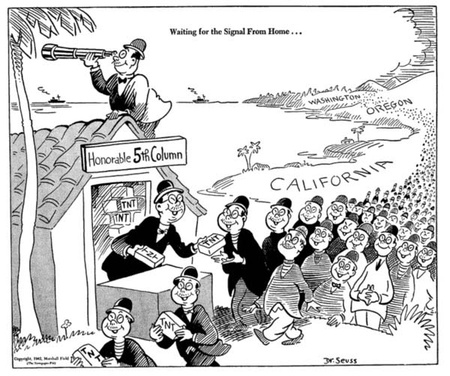

When the war broke out, the U.S. army considered the fishermen to be the “tentacles of the fifth column” of the Japanese empire. Following this same logic, the first people arrested in the afternoon of December 7 were the fishermen. On Terminal Island off the coast of Los Angeles was a large community of more than 3000 Japanese people and their descendants. The FBI immediately removed its community leaders and closed all Japanese businesses. The island became a war zone when the ferry to and from Los Angeles was suspended.

In Mexico, President Manuel Ávila Camacho immediately severed diplomatic relations with Japan as a consequence of the attack. In addition, at the request of the U.S. government, the Ministry of the Interior ordered the fishermen to relocate within 72 hours to Guadalajara or Mexico City.

Totaro Nishikawa, accompanied by other fishermen, asked General Abelardo Rodríguez to intervene with the federal authorities in order to avoid the forced relocation. Forced mobilization meant that immigrants suddenly became unemployed and homeless. For its part, the general’s company, Pesquera del Pacífico, initially tried to stop the transfer because it rightly feared the collapse of fishing production and its subsequent impact on their business interests. The intervention of former President Rodriguez ultimately did not prevent the displacement, but it did at least allow for the first wave of forcibly relocated Japanese Mexicans to leave for Guadalajara and Mexico City later on in January.

Since their arrival, immigrants had created local organizations in different parts of Mexico in order to share information and provide mutual support. The Japanese Association of Ensenada was charged with organizing the forced relocation process. The celebration of one of the most important Japanese festivals, the New Year or shogatsu, became emblematic of the sad and complex moment in history that the diasporic communities were faced with in Mexico.

At the beginning of the new year, Totaro managed to rent a boat in which his wife, brother, and two children would embark for the port of Manzanillo in mid-January 1942. Joining them were Masaharu Sakai, Yonekichi Yamamoto, Kazuto Morita, and Tosini Hidano who traveled with her newborn baby. Tosini was the wife of the fisherman Tetsushiro Hidano who was incarcerated in the United States at the time. In total, about 30 people embarked on the journey; the crossing to Manzanillo would last three days. The fishermen and their families spent one night at the port before moving to the city of Guadalajara. Upon arriving in that city, they reported to the authorities and began to look for a permanent place to live, which turned out to be a large house on the Donato Guerra Street containing several families.

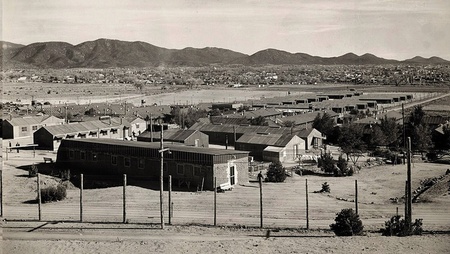

The U.S. government, dissatisfied with the relocation measures being carried out in Mexico, requested that the most important leaders of the Japanese communities in Mexico be sent to the United States. Fortunately, the Mexican government did not accede to this request, unlike certain other Latin American governments. However, fishermen residing in Ensenada were detained in U.S. concentration camps. This was the case, in addition to Hidano, of several fishermen who had the misfortune to leave Ensenada in the days before Pearl Harbor only to be arrested while docked in San Diego on December 10 and accused of being “foreign enemies.” Among this crew of fishermen was a naturalized Mexican citizen, Takeshi Morita, who was not repatriated to Mexico until mid-1945.

Although the fishermen who were forcibly relocated to Mexico City and Guadalajara did not suffer the terrible consequences of incarceration like Morita, this did not mean that they did not suffer enormous difficulties throughout the war. In Guadalajara, the Nishikawas and other fishermen had to find a new means to survive. Fortunately for Totaro, he not only spoke the Spanish language, but had also managed to save a significant amount of money, factors that allowed him to start a small restaurant called “La Frontera”. In addition, Totaro managed to open a salon and a taqueria in Tlaquepaque where he would employ two of his colleagues. Francisco Nonaka would be in charge of the salon, while Guadalupe de Amano, Mexican wife of fisherman Katsu Amano, would take care of the taqueria. These businesses were how the Nishikawas and other Japanese Mexican families managed to get by during the war.

Kazuma Nishikawa initially sought to return to Japan. In September 1942, he moved to Mexico City because the authorities announced a possible exchange of prisoners between Japan and the Allied forces. This would have been the second prisoner exchange that never materialized, and Kazuma returned to Guadalajara in February 1943. In that city, he labored in his brother’s restaurant from 11pm to the early hours of the following day. Mura also worked to supervise the hair salon, arriving every morning with Nonaka to close the accounts of the previous day.

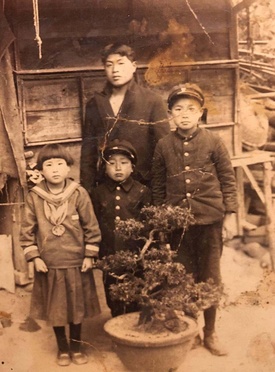

In mid-1943, Mura and Totaro enthusiastically welcomed their third child born in Mexico, Katsuo. However, not everything was joyous in the Nishikawa family, as not only the three eldest children of the marriage but also all their extended family lived on the other side of the ocean. The only way they could hear from them was through letters that took very long to arrive because they were closely inspected by the authorities. The Nishikawas were also very worried because they knew that their eldest son, Masayuki, was in the war front in Manchuria. A letter from the Japanese Red Cross informed them that their son had died. The news devastated Mura, as the enormous pain of his eldest son’s death combined with the anguish of knowing that his two sons and his entire family, even though they lived in Shizuoka, had been the target of the devastating American bombings. The end of Japan was inevitably approaching, and toward the end of 1944 the invasion of Japanese territory by the American armed forces seemed imminent. It seemed to Mura that the only thing he could expect was more devastation and death.

Mura’s fears soon became a terrible reality. The end of the war came when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, leaving more than 210,000 dead in a single instant. The country was also left in ruins; the shattered agricultural system was unable to feed the population. Attempting to move to Japan would be tantamount to self-annihilation, so the imagined return of the Nishikawas and other immigrant families was foreclosed. The main objective of the Japanese Mexican communities then focused on rebuilding their lives and supporting their compatriots from Mexico.

In the spring of 1946, the Nishikawas had their fourth child born in Mexico, a girl by the name of Sayoko. By allowing the Ministry of the Interior to allow the immigrants to return to their places of residence, the fishermen in particular would be among the most sought after and expected in Ensenada. The companies of Abelardo Rodríguez and other businessmen, faced with the “collapse” of fishing production, immediately called on the immigrants who were among the few displaced people that resumed their old activities. Totaro and Kazuma restarted their work as divers, but not for long as the latter met the young Alicia Yakabi, daughter of immigrants, in Guadalajara. He would later marry her in 1947 and would devote himself to manage two shops that his father-in-law had built. Totaro, for his part, worked for a few more years as a diver and later as an independent fisherman in charge of his own boat.

Kazuma and Totaro never returned to Japan again. Shosaku, the youngest son of the Nishikawas to have been born in Japan, was able to come to Mexico to see him before his death in 1965. Mura would die at the age of 87 in 1992. Kazuma had a very long and productive life and died at the age of 98 in Guadalajara in 2016, survived by his wife and four children.

The legacy left by Japanese fishermen, although increasingly tenuous, is still present in the memory of the new generations of fishermen, who remember their teachers in the ports and places where they left a school. The tombs with Japanese symbols and shapes found in Bahía Tortugas and elsewhere, however, form the material testimony to their impact.

@ 2019 Sergio Hernández Galindo, Kiyoko Nishikawa Aceves