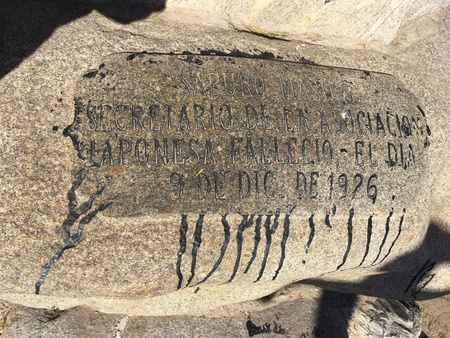

Shinichi Morishita was arrested in December 1926 for the murder of Saburo Mashiko, the then secretary of the Japanese Association based in Mexicali, Baja California. The popular jury that would judge Morishita would be formed almost two years later. The resolution of this body would acquit him, unanimously, of the crime on February 2, 1928; without mentioning in the file the reasons for that decision. However, the acquittal sentence would be annulled by the criminal judge of the Northern District of Baja California. Article 329 of the then current code of criminal procedures of the Baja California territory was considered unsatisfactory. The same judge transferred the case to the Superior Court of Justice (TSJ) of the Northern District of Baja California, which ratified the annulment of the sentence of February 21, 1928 and convened a new popular jury, whose new members charged, by majority, capital punishment to Shinichi Morishita on April 25, 1928.

Faced with this situation, Morishita enlisted the assistance of Mr. Casiano Castellanos Castro to seek protection before the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN) for two reasons: first, the complainant and his defender argued that there were failures in due process as the (first) popular jury had already acquitted him, and even so, the district judge unilaterally declared that such acquittal was not appropriate, and promoted that the complainant be tried again for the same crime before the district TSJ; and second, because from December 1926 to February 1928, the time in which Shinichi Morishita waited for the resolution of his case, he was in prison, deprived of his freedom without trial or sentence.

The file is not clear in indicating whether Morishita committed the crime or not, but the protection that he raised before the SCJN did not seek to be considered innocent, but rather to review the irregularities in due process that violated his constitutional guarantees, specifically the right to not be tried twice for the same crime.

The review of the judicial amparo file does not include other relevant elements about the events that occurred on the day of Saburo Mashiko's murder. In the translation of the History of Mexican-Japanese Relations 1 of 2012 made by Makoto Toda, reference is made to the case of Morishita, where it is clarified that he was the brother of the president of the Japanese Association of Mexicali, Ryoichi Morishita, and that there was another person involved, Kiyoji Ikuta, a gangster linked to the Tokyo Club of Los Angeles. Mashiko was suffocated and hit on the head several times with a blunt object. He was later buried in the Association's inner courtyard before starting the fire in the building.

Both Morishita and Ikuta were arrested by the Mexicali authorities; inside the prison there was apparently a fight between the inmates, killing Ikuta allegedly at the hands of Jesús J. Torres. The account given of that event opens the possibility that it may have been the subject of a “settling of accounts” to avoid the involvement of other people and the Tokio Club de los Ángeles itself. In that sense, Morishita was left as the sole and possible culprit of Mashiko's murder.

The History of Mexican-Japanese Relations also narrates that based on the rumors of the time, the death of the general secretary was linked to the use by the Japanese mafia, which operated in California, of human trafficking using the “Y” system. obiyose ”. Japanese residents in Mexicali were convinced, threatened or bribed to “invite” their future partner, but upon arriving in Mexican territory they divorced. Saburo was in charge of signing the internment permits for the Japanese women who traveled to that border city, and upon verifying this deception (in particular of 5 women) he contacted the Japanese consulate in Los Angeles and the immigration authorities for their deportation from the country. . All of the above marked his future and the decision to eliminate Mashiko Saburo. In the end Shinichi Morishita was released from prison until 1939 through the figure of pardon during the government of Lázaro Cárdenas.

Note:

1. Makoto Toda, History of Mexican-Japanese Relations (Translation of the Nichiboku Koryushi) , Artes Gráficas Panorama, 2012.

© 2019 Carlos Uscanga, Rogelio Vargas