So you’re in camp and there for a couple of years, and then the loyalty questionnaire is put forth to everybody. What do you remember about getting that questionnaire and seeing those two questions, 27 and 28? Can you talk about what you did?

They didn’t tell us about doing away with our citizenship or nothing. But they didn’t warn us. I don’t think there was any warning or nothing. But they had a big cafeteria or gym that we met in, the whole camp. That was all full. The people of draft age, some with their parents. They were all outside, too, saying ‘ra ra ra’ every time Frank Emi spoke. And well, Frank Emi was kind of a leader, huh? To us anyway, to my brother. And I think I myself kind of went with my brother.

So your brother was the one who said ‘I’m not going to answer.’

Yeah they were the first bunch. And they had no question. And people were saying, ‘Gee at their age, they mean it.’

What was your brother’s name?

My brother Kazuto.

How old was he?

He was a year or year and a half older than me.

So you went along mainly because of him.

I think behind my head it was mainly that. Because I always felt wishy-washy.

Did you care one way or the other? Did you feel this is wrong and you were angry?

Oh yeah, I knew this war was wrong. And the way people react to you when you were in school. The very next day we went to school and you could feel the chill. And the teacher calling out, “Mitsuko [inaudible], you ‘Jap boy.’” Oh, he couldn’t—I think he died with that in his head. He was a self-made family, they really made out good. But that was one thing I think he carried with him.

So it was you and your brother. Do you remember answering no/no to those two questions?

I think we were in the second bunch, so I don’t think they even bothered asking us that. Frank was the closest thing to us. He was a judo teacher I think. Although I never took up judo, that was a little too rough for me.

So what do you remember about Frank Emi and his personality?

Oh yeah, he had everything. He was a man of everything. He had his family to take care of. He almost put us in front. Yeah that’s how he believed in us, Frank Emi. And his brother, Art Emi. He’s another one, he was a solid guy, too. There was quite a few solid people. And there was a real old, well, he looked really old to me, I forgot his name. There were quite a few leaders but they stayed behind the limelight.

So do you remember talking with your brother about this and what was going on?

No, by that time he was gone.

Because he was put into the jail?

Yeah. It’s a funny thing, we never ended up behind bars. Like I know when we went, they took us by automobile. There were six to car, that’s including the driver. But you know, the driver himself could’ve been overpowered. But they trusted us that much that they stopped to feed us lunch. We could have run away but they trusted us that much.

And you’re speaking of when you were sent to the trial or the penitentiary?

Just the first bunch went, they had their trial. I know they were saying the judge himself couldn’t understand fully what it was all about. Because they were in camp already. They were already in prison. It was a prison.

And this is when you were sent to go to the penitentiary?

The first group had a trial. But they were saying the judge himself couldn’t understand fully what it was all about. Because they were in camp already, they were already in prison.

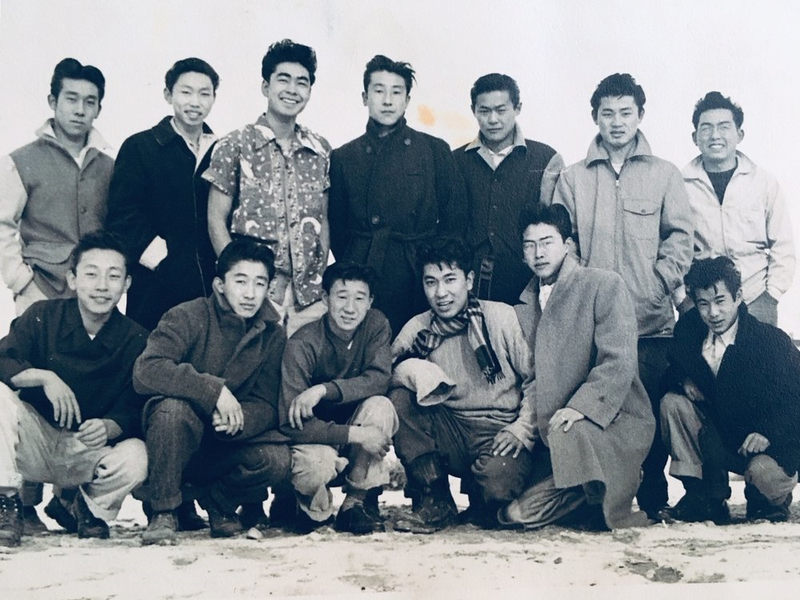

So your brother is in that famous Heart Mountain photo. So your brother spent time in that penitentiary?

Oh what was it? Two years? Almost two years. But for us, it was fun because we never went behind the bars. It was just a big hall. It was an upstairs and downstairs hall. And we all slept where all our buddies were. And there was no “Don’t do this, don’t do that.” We’re all together and we had a box where we could keep our little belongings. We had all the freedom and we got to know the other people that was in prison for other things, you know hakujin. Not Japanese.

There was only one Japanese man in there, we never asked what it was for. But I think he’d done away with his wife or something. But we became very close, ties with him. We used to call him “Ojisan, ojisan.” We played softball in the mornings and hardball in the afternoons. I was a catcher for both. But I think the man had a lot of fun too. And it was the hardest when we had to part with him. He knew before we come what we were there for. I got real close with him. He was telling me where he was from and I forgot. And the way he talked, he didn’t say he’d done away with anybody but to me, it kind of faced that way.

And where were you being held?

It was in Washington near Seattle. It’s McNeil Island.

And you have a story about meeting a man, Daniel Dingham?

We used to play softball against them. We used to do things together. And we’d shake hands and in fact some of them we knew so well we called them by name. I used to go up and just say, “Good game. See you later,” you know? And when they passed by when we were in our quarters, he’d just stop and talk to me, and he’d go on his way.

Do you remember his name or any of the names of the sentries?

Gee yeah, one guy was Phillip. But that’s the only guy I know.

It’s interesting, they didn’t want to be there either I’m sure.

No. I didn’t want to be there, he didn’t want to be there. And they were very, very nice. They were our age, some them, I guess.

Did you go back to high school after this happened?

No, no I didn’t. We figured we had a hard time, we have to support the rest of our kids. Otherwise they would have had to go without school, too and we looked at each other and we said, “We have to help the rest of the ten.” So they all turned out to be good kids, nobody in jail.

Yeah, you had to sacrifice a little bit for yourself.

After we left the prison, we went back to camp and we went to work at the railroad because we didn’t stay there forever. When we were in camp at the time together, we weren’t good boys.

You were giving your parents a headache?

My friend died early. He was from Los Angeles and I got to know him real well, we became real brothers. We skipped out of the gate. You weren’t supposed to.

You mean the barbed wire?

Yeah. We got caught in the light and they said, “Stop! Stop or we’ll shoot!” So we said we don’t have a choice, we better go back. I didn’t know Los Angeles had gangs. We didn’t have gangs here.

Can you talk about leaving the penitentiary and going back to camp?

When it was time to get out, they called in the morning through the microphone, “Come pick up your clothes.” It was the clothes you owned. Then we got ready at about 10 o’clock in the morning and we had to cross the penitentiary because it’s an ocean. Or it’s like an ocean, Seattle. And gee after that, I don’t know how the heck we got—I think they took us in a car to a certain place and put us on a bus.

And before we went home, we had a choice. Going to work at a railroad company or just go home. And most of us took the work at a railroad company and it was Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul and Pacific Company. They welcomed us. And even the foreman, the bigwig there, he really took us in. And he would take the guys that wanted, even the first day, to go hunting. I took non-hunting I came out here to work. There’s always a river following the train track over there. It’s hilly, it’s a beautiful, beautiful place. If you go there in November, December, you would hate to go home. You see the valley, down below is the city and there are logs here. The train company owns almost everything there. Boy you think, how beautiful. But a lot of guys said, “To hell with it.” But to me that was beauty. To see only ugly images, I’d like to see beauty.

We lived in one of their trailers. And the trains were going that way, and we lived in the other one. And only that much away from the other way—if you put your hand out, I think it’d clip ya, you know? But it traveled that close.

How many years did you work on the railroad?

It was about a year and a half. Quite a few of us stayed behind. It was fun. And Sunday I used to walk up and down. They’d say, “Eh, stupid.” But it was so pretty, boy. I used to walk the railroad and they used to have gravel on the side, they would beautify the gravel.

I used to go up and down, up and down every Sunday. And one day I found an agate about that big. All pure red. And the foreman would say, “Boy you never see one like that around here.” I was one of the guys that found it. And we had boxes right above our bed to put our clothes in. And I left it right on top because we were all Japanese. And lo and behold somebody stole it. And then the foreman said, “Boy that’s unusual because Japanese don’t steal things.” That’s why I left it there and by god somebody stole it. I could’ve made a big ring out of it. You could’ve shown off that ring, boy.

And where were your parents at this time?

They were still in camp. And I don’t know how much longer, but they moved back. We were worried, I was worried but I found out that my folks were right back where they started. The good people hired my father back and they were already settled. But boy I would’ve loved to stay in that railroad place, you know? It would’ve been pretty but everybody got tired. We kind of wanted to leave. Some went to San Pedro, some went to L.A., we went to the Valley here. All over the place scattered.

What was resettlement like for you? Was it harder than camp and did you face any kind of discrimination when you came back?

Yeah for a while yes, I got to say yes. Although I didn’t see too much of it but you could hear people say ‘Japs’ and that thing.

And you have a story about your parents’ property?

They lost it all, we had to start right from the very beginning. Somebody held it for them but a lot of it was confiscated.

And you came back, and did you start working?

Yeah we started right away, my brother. We ourselves were lucky I think. Very lucky. We didn’t go through that much headache. Part of it was my folks already had things, we got there late.

Did your parents ever say anything to you or talk about their experience?

Nope, no never. Too many kids, too much to worry about.

[And I had a friend] who was pretty well-off. They had their own ranch, had a nice car. And he just passed on. And I think he was one of the closest friends I had from the same place we were, but he just passed away. You get lonely, all of them pass on. And you hear these things from Los Angeles, San Pedro, all over. ‘This guy passed away. This guy passed away,’ and then your morale goes lower and lower. I often think about those guys because we were like brothers, living together.

I’m curious when you came back, or maybe in your later life after the war, did you face any backlash because you resisted the draft?

Nope, not even from my friends, not even from my brothers. Maybe I should’ve, but I didn’t. As a matter of fact around Berryessa, there’s two hakujin from two different churches who are very close to us. That’s because they were there too. They’re the head of their churches.

And you lived your whole life in this area?

I was born in a San Jose hospital. And my three children were born in the same place.

You just really put down your roots here. And what did you do for work in your later life?

I was a gardener. I got interested in it and when the kids grew up a little bit I was still interested in it. I took classes for it.

And I’m curious about you meeting your wife, can you talk a little bit about her?

I met my wife over here. I thought she was the nicest person. Low profile, and quiet. So we got along real well until she had bad health. She said, “Please don’t help anymore. I hurt so much.” That was the hardest thing I did, just didn’t do anything for her. I just saw her fade away. I just thought, “Oh god, is this the end?” After so many years I got used to it, and depend on my family, my kids.

But you had good years together with her.

I wish there was a way you sign a paper that says when your wife goes, you go with her. It’d be easier for me. I always thought that’d be so nice.

What was your wife’s name?

Mitzie Mutsuko Sugara. She was from Pasadena.

I’m curious about your feelings about redress and when you received the check and the apology for it, what were your feelings about all of that?

I didn’t feel nothing. I didn’t care, I really didn’t. My friends, too. They said the hell with it, let it go. ‘They didn’t like us, we don’t like them now.’ I didn’t give it much thought. I should’ve but yeah, that was a lousy history.

This interview was made possible by a grant from the California Civil Liberties Public Education Program and the Japanese American Museum of San Jose.

* This article was originally published on Tessaku on April 2, 2019.

© 2019 Emiko Tsuchida