Once upon a time, in the small village of Ruskin, there was a little girl named Reiko. She loved her life in the Fraser valley where her father taught her how to fish, using only a string and a safety pin. She and her two sisters spent precious summer days with their father who took valuable time away from his work as a salmon fisherman… to make sure his daughters knew he loved them. In the winter, he would hitch up his horse, Prince, to a sleigh and they would go deep into the woods to find the perfect Christmas tree.

When Reiko was 10 years old, something marvelous happened. She became a princess. She was chosen by her classmates to represent Ruskin for Queen Victoria’s May 24th birthday celebration in Haney. She loved the beautiful scalloped organza dress which her sister made for her. She had never had such a beautiful dress.

What was remarkable was that a Japanese Canadian girl could ever become a princess. What was even more remarkable was that it was not a Japanese celebration. She was a princess in a celebration for the predominately British community. Reiko was very proud. So were her parents. Reiko’s family was finally accepted as Canadians.

Then, when Reiko was 18, she was hired as a housekeeper in the mansion of the mayor of Vancouver. The family loved her and Reiko loved them. She thought that she would live happily ever after… But dark clouds gathered over Princess Reiko’s ever after.

One dark and stormy Sunday, happily ever after became hell on earth for Reiko. She was no longer a princess. She woke up. The fairy tale was over.

December 7, 1941…. Reiko’s whole world exploded. Japan had bombed Pearl Harbour and declared war on the United States. The day after the disaster, Canada declared war on Japan. Soon the Canadian government announced, through the War Measures Act, that all 22,000 Japanese Canadians had to give up their homes, their businesses, and their possessions and move 100 miles away from the coast, to internment camps or to work on farms in the Prairies… even though most of them were Canadian born. Reiko couldn’t understand what was happening. She was like all other Canadian teenagers. She loved the Foxtrot and Frank Sinatra.

Reiko begged the mayor to help her family but he turned his back on her. He could not go against the Government of Canada. Fear gripped Reiko’s heart. She could not breathe. What were they going to do?

Then the government gave them only 24 hours to move out of their home. Reiko’s family were in a panic. So hard to know where to go in so little time!

Finally, Reiko’s mother decided that her family would to go to Alberta so that everyone could stay together. Internment camps were only for women, children, and the very elderly. Able-bodied men had to work in road camps, clearing rocks after blasting… wheelbarrow load after wheelbarrow load, all day, every day. No one in the internment camps would know where their men had gone.

When Reiko’s family reached Alberta, they were treated horribly. Here is Reiko’s account of what happened:

In May, 1942, we arrived at Lethbridge, Alberta, by train with other evacuees, and we were escorted like convicts by the RCMP. Our clothes were totally inappropriate for farm life and the harsh Alberta winters. We were city people with city clothes. We no longer had a home. This was the most terrible time of our lives. We were rejected by our own country, and no-one spoke up for us.

The so-called “house” was a converted chicken coop, which was extremely cramped for the nine of us. There were Eunice, her husband, her three children, my parents, Rosie and myself. We barely had room to cook, eat and sleep. The room was filthy with chicken droppings all over the place. There had been a window but the glass had been broken and slats from orange crates had been hastily nailed over the opening. We had an old broken-down screen door with cardboard nailed onto it as our door. Mother hung a comforter on it to try to keep out the cold air, but it was useless. The coal stove was kept going night and day to keep us from freezing, but we were always cold. We had come from very moderate winters in Vancouver to the very bitterly cold prairie winters which often dipped to thirty or forty degrees below 0 Fahrenheit. The farmers were supposed to provide us with proper housing and bedding, but this farmer provided neither. All we got for bedding were sacks filled with straw.

The conditions were excruciating, but somehow they survived. Reiko’s fiancé was finally given permission to marry her in 1944. Reiko had a baby in 1945. Eunice also had another baby. Now there were 12 in the one room. So you can imagine the bickering. “Who ate the last orange?” “It was your turn was it to get the water.”

Reiko and Hisashi finally decided to move to another farm nearby when the fighting became unbearable. They had to build their own house so Reiko got a blueprint for building a basic house and read them to her husband as he worked. They lived in that one room house for six years after the war was over, with two small girls. Reiko almost died from kidney failure and lost her third child, who would have been a boy. Her husband took the youngest girl to an elderly Japanese Canadian couple while he completed the topping of the sugar beets with his eldest daughter on his back. Reiko lived, after 40 days in the two-room hospital in Coaldale.

After the war ended, Eunice’s husband was deported and she stood by him. They went to war-torn Japan where they were treated badly by the Japanese. “Go Back where you came from!” “You are taking our food!” “We don’t want you here.” “You are the enemy.”

They stayed for fifteen years because the Canadian government refused to allow them to return. Reiko’s father died there and Rosie contracted Tuberculosis. There was no medication in Japan so they were finally given permission, in 1962, to come back to Canada. Too late for Rosie. She died in Vancouver, British Columbia. She was only 37 years old.

Reiko and Hisashi had refused to go to Japan with the family and stayed in Canada. They slaved from dawn to dusk working the 10 acre sugar beet field for ten years, earning only $900 per year between the two of them. An appalling wage, even in those times. In 1947, the lowest average family income was $7,800 per year.

For Reiko and Hisashi, every penny counted. They grew and canned their own vegetables, made underwear from flour sacks and furniture from orange crates. Reiko’s husband took other jobs in the off-season for sugar beets - building grain elevators, working on potato farms, and travelling to logging camps in B.C. during the winters. Finally, they saved enough money for the train fare to Ontario. Finally, the storm clouds lifted.

Reiko…was…my mother.

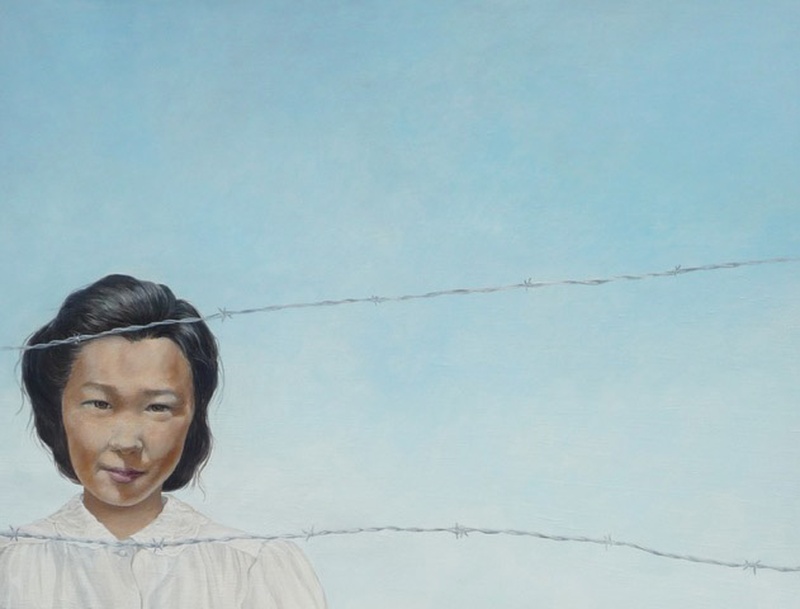

In 2009, my mother passed away, I painted this portrait of her which has become the iconic image of the Internment of Japanese Canadians. Her face is the signature image for the Royal Ontario Museum’s current exhibition “ Being Japanese Canadian: reflections on a broken world”.

But even before this exhibit, her face had been on the cover of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre newsletter in 2012. Her face was also the signature image for a major exhibition in Vancouver in 2016, “Absence in Remembrance”, sponsored by the University of British Columbia. She was also recently featured prominently in Hyperallergic, an arts magazine review of the ROM exhibit, “Contemporary Artists Reflect on Japanese Internment”. Most recently, her face was on the front page of last month’s issue of the Nikkei Voice, the national Japanese Canadian newspaper and the Bulletin.

This image of Reiko resonates with people because it represents the Japanese spirit of strength and determination for a better future - to be strong in the face of their horrendous loss of everything, to make sure their children thrived, without hatred, in a country which had betrayed them so long ago.

A young woman looks straight into the eyes of the viewer, dressed in city clothes, behind two strands of barbed wire fence which separate her from the viewer, against a large expanse of clear blue sky. She does not flinch. She accepts her fate. She is not defeated. Neither is she angry, nor bitter.

Reiko’s face is the face that greets the world. But no one sees her inward face, the face of shame, the face of pain. Perhaps that is why the Japanese are viewed as inscrutable, two-faced. Yes, we are successful but we hide the price we have paid to keep our dignity, generations after the war - our loss of culture, our loss of heritage, our loss of language, and our loss of identity. It is only now, 74 years after the war and 30 years after redress by the government, that we are beginning to heal from the forced removal from our homes, to believe in our hearts that we did nothing wrong.

I wish that my mother had lived to see how much her face meant to so many people.

As a Sansei, a third-generation Japanese Canadian, it has taken me all my life to come to terms with the past and my own denial of my people and my heritage.

It took me my entire life to forgive the broken world of the past and love who I am, to grow from hating everything Japanese to forgiving myself and releasing the burden of shame.

Redefining Home, a recent exhibition at the Campbell House Museum in Toronto, is the best expression for the Japanese Canadian journey. I am reminded of two sayings. “Home is where the heart is” and “Grow, where you’re planted.” That is what all Japanese Canadians did when we were relocated from our homes. A new beginning. A fresh start. Perhaps that is why the Issei and the Nisei wanted to leave the shame in the past. We can’t change the past, but we can redefine our home.

I have had twenty-nine homes in my life. I think that the Japanese Canadian experience had lasting effects on who I am. The isolation in Alberta during my formative years left me with no sense of belonging to a community, any community. I am constantly redefining my home. I am always an outsider looking in, straddling two cultures, adapting to new environments, searching for my identity as a Canadian who is Japanese.

I have learned much in my long journey. I am thankful for the life I have had as a Canadian, as someone who has never lived through war, and for the protection the Nisei gave us… even if it meant the sudden end of the Japanese DNA line in Canada in just a single generation, the Sansei. However, the work being done by so many Yonsei, the fourth generation, is proof that we are still continuing Japanese values, just in a different skin. We are gradually becoming less a visible minority and more a part of the whole. But the core values of what it means to be Japanese is still with us – to be the best we can be, to honour our families, to instil in our children the value of education and respect for our elders… to be …proud Canadians.

In the three quarters of a century which have passed since WWII, Japanese Canadians have prospered again all across Canada. Like the ancient Phoenix, we have risen from the ashes and found hope for our dreams, in places we never even imagined when we lived so long ago… in the beautiful Fraser Valley.

Once … Upon a time.

*This article is a revised version of Lillian's speech given on the last day of the exhibit, Redefining Home, shown at the Campbell House Museum, March 1 – April 1, 2019.

© 2019 Lillian Michiko Blakey