While growing up in post-WWII Hawaii of the 1950-1960’s, I knew only two things about my father’s wartime service: he was with the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) in the Pacific theater, and he had been on Saipan.

To say my father was parsimonious regarding his WWII exploits would be a gross understatement—he usually responded to questions with a couple of “harumphs” or what seemed to be his favorite expression, “Let sleeping dogs lie.”

If not for my mother’s references to fairly regular visits from the FBI during the war, my siblings and I probably would not even have known of the MIS connection—she explained that my father was with military intelligence and the FBI wanted to know what he was writing in his letters home from overseas.

I knew of his time on Saipan only because, when I was nine-years old, two journalists, Fred Goerner and Ross Game, came to our home during the fall of 1962 to question him about a Japanese prisoner of war (POW) captured on Saipan in July 1944. The POW allegedly had in his possession a picture showing Amelia Earhart standing near Japanese aircraft on an airfield. According to the journalists, the POW reported that the woman in the picture was taken prisoner along with a male companion, and the POW thought they both subsequently were executed. My father was one of three MIS interpreters, along with Roy Masami Higashi and William Y. Nuno, who might have interrogated the POW. As was his custom, my father deflected Goerner and Ross’s questions concerning his military service citing lapses of memory and referred them to Higashi or Nuno. I learned later from reading Goerner’s 1966 publication, The Search for Amelia Earhart, that Higashi and Nuno had done exactly the same when confronted by Goerner.

Some 35 years after Goerner’s interview, my father finally relented to my periodic revisiting of the subject, acknowledging that he had interrogated the POW with the photograph. He put it very plainly--there were more important, pressing matters to deal with at the time than an “archeological dig” so he forwarded the POW and the picture on for higher headquarters to sort out. That was all there was to his involvement, and that ended the matter.

Everything else I eventually learned about my father came from third parties, publications, or documents found after his passing. Since he said so little about the MIS, we knew more about other relatives’ exploits in North Africa, Italy, and France with the 100th Infantry Battalion, Separate, (100th BN) and 442nd Regimental Combat Team (442nd RCT).

To my surprise, while reading Joseph D. Harrington’s 1979 tribute to the MIS, Yankee Samurai: The Secret Role of Nisei in America's Pacific Victory, I discovered that my father was already in uniform when Japanese Imperial forces attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941—he was loading a machine gun on the back of a truck at Schofield Barracks to help repel the air assault. According to his service records, he was drafted in June 1941 and served continuously until discharged in November 1945.

While researching his own family’s service history, a cousin found that my father initially served with the 298th Infantry Regiment of the Hawaii Territorial Guard until it was consolidated with other Nisei members of the 299th to form the 100th BN in June 1942.

Assigned to B Company, he and the other members of the 100th BN shipped out for Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, for combat training. According to the writings of 442nd RCT/ MIS wartime historian, Ted T. Tsukiyama, while at Camp McCoy, my father and 58 other members of the 100th BN were drafted for intelligence specialist training and transferred to the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) at Camp Savage, Minnesota, in December 1942, forming the “senpai gumi” of Hawaii Nisei to enter the MIS.1

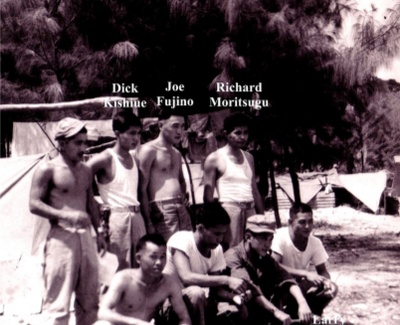

According to his MIS teammate, Nobuo Dick Kishue, after graduating from 26 weeks of schooling in the Japanese language, he, Tim Tokuyuki Ohta, Hoichi ‘Bob’ Kubo, Shigeo ‘Jack’ Tanimoto, Joe Yuzuru Fujino, Larry Yoshimi Saito, Higashi, Nuno, and my father were sent to Schofield Barracks in Hawaii and assigned to the 27th Infantry Division. Kishiue, Tanimoto, and Kubo were temporarily detached to support the invasion of Makin Island in November 1943. According to his records, while Kishue et al were at Makin, my father was deployed elsewhere in the Gilbert and Marshall Islands (Central Pacific Campaign, 1943-1944) before the entire team joined in the June-July 1944 invasion of Saipan (Western Pacific Campaign). His final deployment before separation from service was the invasion of Okinawa (Ryukus Campaign, March-July1945).2

Notes:

1. Tsukiyama explained that “senpai” translated into English means “elder,” “senior,” “predecessor” or “pioneer,” and the word “gumi” means “group,” “team,” or “class,” so “senpai gumi” as referred to herein means “pioneer group” or “pioneer class.” “Senpai Gumi” is also the title of an anthology edited by 100th BN/MIS veteran Richard S. Oguro, which tells the story of the initial group of 59 100th BN Nisei soldiers who were transferred from their Camp McCoy training to the Camp Savage MISLS.

2. After four years, four months, and 19 days of military service, Richard Yutaka Moritsugu separated from the MIS as a Technician 3rd Grade (equivalent rating of a Staff Sergeant). He was awarded the American Defense Service Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Service Medal, Good Conduct Medal, Bronze Star Medal, and Unit Citation for Meritorious Service (27th Infantry Division).

*This article was originally published in JAVA Advocate in Spring 2015, Volume XXIII - Issue 1

© 2015 Bob Moritsugu